Goldie Hawn portrays a Russian ballerina who falls in love with an American correspondent (played by Hal Holbrook) in the 1974 film, "The Girl from Petrovka." Source: Kinopoisk.ru

{***"The Girl From Petrovka” conveys the Soviet spirit in an American way***}

This is a story about a story. Although the original is mine – meaning I expanded the first story into a novel I hoped would convey some of the spirit of Soviet life – its so-to-speak sequel, upon which I remain a puzzled onlooker, is more interesting: further confirmation for anyone who needs it that fact can be stranger than fiction. But the facts here are somewhat complicated. To put the summary less abstractly, the leading character of my “The Girl From Petrovka,” published forty years ago, came to life far beyond the powers of my pen, and she, my invented Okyabrina, still mystifies me.

That’s why my decades-long search for a key player of story two, the former correspondent of a prominent American newspaper, is becoming more desperate. He may be dead: to be more specific, story number one, my novel, was published in 1971. The said Moscow correspondent of non-fictional story two was full of confidence as well as surprise when he informed me that the girl from Petrovka was no creature of my imagination but a living, still restless person.

He told me a friend and fellow Moscow correspondent of his, who represented the Baltimore Sun forty years ago – and whom I’ll call Joe for a reason that should become clear in a minute – answered a telephone call to the Suns’ office from a woman whose voice was unmistakably young and full of exceptional determination in the service of daydreams. That was a good fit for who she said she was.

“I’m the girl from Petrovka,” she declared. “I’ve served my term and I’m out, so can we meet?” She’d called the Sun because the male protagonist of “The Girl From Petrovka,” of course fictitious, was its Moscow correspondent, who, by the end of the book, dimly realizes he’s fallen in love with the imaginative Russian lass of the title. And now that she was “out” – out of a relatively mild labor camp – the real person wanted to meet that particular journalist: after serving a sentence of several years, she’d no doubt need help in smuggling herself back into Moscow.

This was moving but also confounding. How did the former camp inmate who had called Joe know about him? And who was she to begin with? Not really, not possibly the girl from Petrovka because apart from the book’s make-believe, there was no such person. It was, I won’t apologize for repeating because I remain baffled, a work of fiction, a slightly fanciful, half-satirical novel that of course hadn’t been published in Russia.

However, a young woman, a real one, had been sentenced to a labor camp for transgressions on which the novel drew in its narration of its female protagonist’s Moscow adventures. And in the book I had her, my fictitious heroine, pronounce the name of the Baltimore Sun’s correspondent—a job I’d picked out of the hat for my male protagonist – “Zhoe” for Joe.

According to the Izvestiya feuilleton that inspired my tale, the shameful young criminal, as the Soviet authorities chose to see her, wasn’t registered to live in Moscow, which made her residence there illegal to begin with. More than that, she was “a parasite,” meaning she had no visible means of support; certainly didn’t work in any capacity approved by “the teachings of V. I. Lenin.” Without overtly calling her a prostitute, the article hinted at that by mocking and bemoaning her supposedly scandalous way of life that included a series of lovers and devotion to all kinds of frivolous activities, including dressing in unorthodox clothing and spending days and nights in one or another form of freeloading pleasure instead of joining the struggle to build socialism by contributing socially useful labor.

In short, she seemed to me a free spirit, which is what attracted me as a model for my flighty heroine, the irrepressible Oktyabrina. (The old Russian calendar had the November Revolution taking place in October.) So while make believe, she was based on that element of truth.

An excerpt from Izvestiya’s coverage of her trial:

“Once again, the court asks you to consider your behavior. Don’t you regret the way you lived?”

The defendant: “I lived the way I wanted to. I don’t see what’s wrong with that. I mean, I didn’t hurt anybody, did I?”

{***“The Girl from Petrovka” goes to Hollywood***}

“The Girl from Petrovka” goes to Hollywood

The making of the 1974 film told at least as much as the novel had about life’s meanings and mysteries. All set for filming in Yugoslavia, its permission was cancelled and crew expelled at the last moment because the Kremlin was in one of its periodic rages against Belgrade, which appeased it by abandoning its participation in an undertaking that was certain to offend the wholesome Soviet proletariat. When the Sunday Telegraph of London sent me to Vienna to write about the shooting that would be resumed there, a secretary in the unit office scolded me roundly when I reached for a copy of the shooting schedule.

“Who do you think you are?”

“I…I wrote the novel.”

“What novel? So what?”

Goldie Hawn, the female lead, agreed in her way by suppressing a yawn and allowing that she’d given up trying to read it after a few pages. On the other hand, The New Yorker’s wild praise – “the only good American novel about modern Russian life I can remember… Oktyabrina Matvyeva joins the ranks of memorable – and heroic – women of modern fiction” – came with all sorts of deep meanings that had never occurred to me. And my fifteen minutes of fame would arrive with globe-circling news of an episode involving Anthony Hopkins, the male lead. Unlike Goldie Hawn, Hopkins was determined to read the book, but couldn’t find a copy in London bookshops. Waiting for an underground train to take him home, he ignored repeated warnings to never touch an identified package because the threat of IRA bombs were then disturbing the city’s peace. The wrapped object he picked up from where it had been lying on a station bench was the very book he’d set out to buy, a one in a million shot – but actually closer to one in a hundred million because it was a proof copy I’d lent a friend months before, begging him to be careful with it because I’d marked it up with a red pencil. He lost it the same day, somewhere in London.

|

| Goldie Hawn. Press Photo |

“What a coincidence!” Hopkins enthused. “But why was it dotted with red spots, have you any idea?”

Now I’m still looking for the Baltimore Sun correspondent whose name I lost together with that of his friend who told me the inventive “girl” had called Joe and was trying to sneak herself back into Moscow, from which she’d been banned. Since she’s surely in her sixties now, I don’t have much time. I want to hear what happened to her before and after her imprisonment. Together with that, I want to start repaying all I owe her with some of the luxury Izvestiya berated her for loving, starting with a delicious dinner. Meanwhile, the moral of the story may be plus ça change, plus ça reste la même isn’t always true. Russia’s startling changes since my novel appeared include ethics and activities that are nearly opposite in some ways to those imposed by the old socialist austerity and Puritanism.

Russians’ apparent determination to disconnect with their former selves is what makes Goldie Hawn’s fairly recent account of her participation in the film relevant. The largest of its inventions and misunderstandings – Ms. Hawn seemed driven to muddle things even more – may have been her assertions that “The Girl From Petrovka” was a “true story” and that “poor George,” meaning yours truly, had a hard time when Oktyabrina, that creature of my frail imagination, was sent to Siberia, a place not mentioned in the book.

Still, Goldie’s impression of Russia from a brief visit in 1973 for absorbing its feel before the filming, was perceptive about what enamored many old Russian hands during my years there as a student and journalist. Although appalled by spirit-crushing Soviet rules and restrictions, she fell in love with the Russian people, “with their passion, their longing, their spirit…For the first time of my life, I began to see that material wealth really doesn’t bring a sense of well-being or contentment.”

One more thing puts a sad ending to both stories, in a way – I hope temporarily, until I can solve the story one-story two mystery. The Baltimore Sun’s Moscow bureau no longer exists. It was closed not for lack of interest but as a victim of the budget squeezes that have cut the number and variety of American bureaus by more than half. Is that progress?

{***Recreating the spirit of a distant place by Nora FitzGerald***}

Nora FitzGerald of Russia Beyond the Headlines spoke to George about his book 40 years after its first publication.

RBTH: How long did you live in Moscow? What brought you there and what brought you home again?

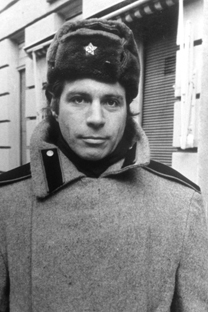

|

| George Feifer played a Red Army soldier in a movie based on his novel. Press Photo |

George Feifer: I lived in Moscow for about ten years, on and off, including one as a graduate student at Moscow University. The need to recover from excessive emotional stimulation brought me home.

RBTH: What prompted you to write "The Girl from Petrovka?"

G.F.: Not to compare Russia during the late Soviet period to Germany during rise of the Nazis, some of Christopher Isherwood's great "Goodbye to Berlin" became my model because its story about an adventurous young woman seemed to recreate the spirit of a distant, often incomprehensible place. I mean the doings of Sally Bowles that became the basis for "I Am A Camera" and "Cabaret."

RBTH: Did you anticipate how enormously well received “The Girl from Pretrovka would be?

G.F.: I prefer not to answer trick questions.

RBTH: You also played an extra in the film. What is your fondest memory from the filmmaking?

G.F.: That it took place at all, after the crew was booted from Belgrade. Too many movies die before the first day of principal filming when broke free-lancers traditionally get paid.

RBTH: Of all your books, concerning Russia, do you have a favorite? What can you tell a new reader about "Moscow Farewell"?

G.F.: That it came closest to saying what I wanted to, and the complimentary comments Russians still send me almost make it all worthwhile.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox