Drawing by Niyaz Karim

On Sept. 2, the 24th Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit opened in Vladivostok, Russia. The forum, which was established in 1989 and includes 21 Pacific Rim countries, represents 42 percent of the global population and 55 percent of the world economy’s gross product. It is highly likely that this century will see the gravity of international politics shifted to this region.

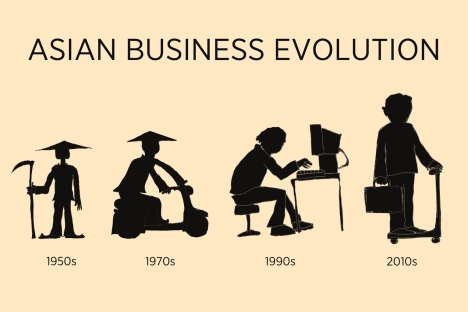

It is in this region that trade wars abound and new geopolitical conflicts are born. In the last 50 years, the Pacific Rim has also witnessed some of the world’s most astonishing ‘economic miracles’. Japan emerged from desolation to become the second-largest economy in the world in the 1950s–1970s; Singapore evolved from a village into the world’s most global city in the 1970s–1990s; South Korea underwent a perfect transition to an open-market economy and, later, to a democratic society; California became a global innovation center; China transformed itself from a poor communist country into the largest exporter of modern industrial products in the world.

Russia’s involvement in Pacific Rim economics and politics is unacceptably poor. The problem is not that the government has failed to pay sufficient attention to the east in its foreign policy; nor is it the case that the government is against the idea of making Vladivostok its capital (an idea proffered by many leading political scientists). The problem is that the country has nothing to offer to its Pacific partners.

Russia’s traditional strength is its natural wealth - at least, this is what Russians have been led to believe. However, the Pacific region is also rich in resources. The most intriguing economic development right now is the confrontation between ‘technological’ economies and ‘industrial’ economies. In the 1990s, the ‘post-industrial’ world seemed to outpace Asia, with scars from the 1997 financial crisis still fresh in the east. However, an industrial renaissance appears to have gained momentum recently. Technologies are becoming cheaper worldwide, while the global population is becoming wealthier and maintaining high demand for industrial products. Russia remains on the sidelines of this trend. The entire country has had fewer international patents registered than the Korean company Samsung alone, whereas China’s investments in innovative development are 40 times the amount Russia invests in innovation.

Financial relations are equally important in the Pacific. Tense financial ties stretch across the region, although giant financial institutions have been formed on the Pacific Rim’s west coast. Seemingly, Russia has nothing to offer its partners, who may be ready to consider Russia their ally in the face of China’ growing power on their borders.

Russia’s plans to play a major role in international logistics are also unfeasible: Russia requires about $35 billion to modernize its two Siberian railways, and simple calculations show that the project is unprofitable. The flow of merchandise between Asia and Europe does not call so much for fast delivery as it does predictable schedules and consistency‒ two things that still leave much to be desired in Russia.

Therefore, the only thing Russia can offer its partners is the ‘national idea’ of its elites, i.e. luxury. Not one APEC summit of the last decade has taken place in facilities built specially for the event, and a host country has never spent more than $100 million staging the event. It is a completely different story in Russia: the 24th summit has cost more than the previous 23 put together. On the plus side, Vladivostok residents will get to make use of some of the newly-built facilities after the summit concludes. And, indeed, the summit. will be over soon, leaving Russia, a country that our forefathers turned into a Pacific nation once and for all, pondering over what needs to be done next. Unfortunately, many experts still focus on water and natural resources, forests and the untapped potential of agribusiness and transport. They seem to be looking for ways to break away from Russia’s excessive reliance on raw materials in the Far East, but I would beg to differ. In order for Russia to try and restore its status as a great Pacific nation, the country needs a large-scale project to re-explore Siberia.

Asian experience would be invaluable if such a project were launched: the development of industrial production, economic openness and focus on collaboration with partners and neighbours.

If Russia opts for industrial development, it will find out very soon that China is its main competitor. It is impossible for Russia and China to work together on this project, because China perceives Russia exclusively as a supplier of raw materials, as well as a mouthpiece through which to voice the anti-American slogans that it does not want to voice itself. Therefore, Russia should seek support from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and all the more so because it has something to offer these three: a peace treaty and a group of islands that no one wants for Japan; pressure on Juche leaders and the possibility of reuniting the North and the South peacefully for Korea; diplomatic relations and international support for Taiwan, as an alternative to following the decisions of the communist party in Beijing.

Russia’s Far East must become a powerful industrial platform from which to process resources and manufacture goods that would be competitive in foreign markets. Japan and Korea are the world’s largest producers of commercial ships and port builders; the infrastructure of the Far East should be turned towards the ocean, instead of towards domestic inland transportation. The new Russian model should copy America’s: two powerful industrial and service clusters on the two shores and agriculture and raw-materials clusters between them.

Within the Russian Far East, Primorye could become a large, export-oriented industrial area with preferential taxation regulations and vast opportunities for international cooperation. These are not idle words. Sakhalin took several years to transform from a subsidised constituent of the Russian Federation into a donor region, after the Americans and the Japanese built an LNG plant there.

As a Pacific country, Russia needs a normal industrial economy that focuses on the global market. And therein lies the region’s very strength: every decade, a new economy seems to emerge from nowhere, proving that such an economy can be built during any phase of development.

Vladislav Inozemtsev, Doctor of Economics, is Director of the Centre for Post-industrial Studies.

First published in Russian in the Ogoniok magazine.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox