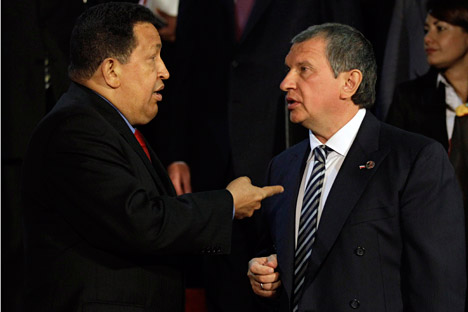

Despite Hugo Chavez's presidential victory the risks for Russia's private oil companies are too high. Pictured (L-R): Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and Rosneft's Head Igor Sechin. Source: AP

{***Stepping up energy collaboration***}

In recent years, the Chavez regime in Venezuela has become Russia’s most reliable political ally in Latin America and the largest consumer of Russian weapons in the region, as well as an attractive investment option for Russian state-owned companies.

In late September, a few weeks before Venezuela's presidential election, a huge delegation from Russia paid a friendly visit to Venezuela. Rather than being led by an official, the delegation was headed by Igor Sechin in his capacity as president of state-owned Rosneft.

Fluent in Spanish and in close association with Vladimir Putin, Sechin has been the principal conduit of Russian interests in Latin America in recent years, and, according to sources in the Russian Foreign Ministry, the Kremlin’s informal curator of relations with the region.

Stepping up energy collaboration

This time, the Russian mission to Venezuela was timed to coincide with the launch of one of the country’s largest business projects with foreign partners: the start of oil production at the Junin-6 block in the oil-bearing zone of Orinoco River, under a joint project between PdVSA and National Oil Consortium (NOC).

Work on the super project began back in 2009, while the consortium itself (consisting of Russia’s largest oil firms – Rosneft, TNK-BP, Surgutneftegaz, Lukoil, and Gazprom Neft) was conceived by then Deputy Prime Minister Sechin in 2008.

Eye-witnesses at the opening ceremony reported that Sechin took childlike delight in bringing the first oil on stream. Following the ceremonial "bath," and with oil-streaked cheeks, Sechin told reporters about the historical significance of the event and described the prospects for business in Venezuela.

The scale of the project is truly staggering. PdVSA and NOC estimate the reserves of the Junin-6 field to be at 52 billion barrels, with a production rate expected at around 450,000 barrels per day. Experts put the investment figure at $10-15 billion. However, it remains to be seen how lucrative Russia’s oil ventures in Venezuela will actually be.

NOC was created almost overnight on Sechin’s direct orders, recalls a top manager at one of the consortium members, in an interview with KommersantVlast. “Sechin announced out of the blue that there was work to be done in Venezuela. That was the result of his foreign policy talks with Hugo Chavez," the manager stated.

NOC was initially registered by Rosneft with an authorized capital of just 10,000 rubles (around $325), after which stakes were purchased by the remaining participants. The board of directors is composed of the heads of the five member companies, plus Sechin himself as chairman.

{***National Oil Consortium is in limbo***}

National Oil Consortium is in limbo

Not all the companies were burning with desire to be a part of the consortium. The most reluctant was Surgutneftegaz.

“Vladimir Bogdanov fought tooth and nail to stay out,” a company source said of Surgutneftegaz’s CEO and co-owner.

Bogdanov’s skepticism is well-founded. The Russian investors will have to shoulder some colossal costs: according to sources for Kommersant-Vlast, PdVSA has not invested a dime in Junin-6. Under Venezuelan law, a foreign investor can only be a minority shareholder, generally with no more than 40 percent — the rest goes to PdVSA.

For its 40 percent slice of the project, NOC has already paid PdVSA a bonus of $1 billion – $200 million from each company. On top of that, NOC will have to assume the exploration and development costs, even though PdVSA has promised to compensate them as soon as the project hits full capacity.

Another complex factor is that almost all Venezuelan oil is of the extra-heavy, highly viscous variety. To make it suitable for transportation, it has to be “upgraded” in a special unit to improve its properties. NOC has to bear the cost of that, too, which could be another $7.5 billion.

Media coverage of the startup of production at Junin-6 was accompanied by other news: shortly before the Russian oil delegation’s visit to Venezuela, it was reported that Surgutneftegaz was on its way out. Its share will be acquired by Rosneft, supplanting Gazprom Neft as the project leader.

“The decision taken by Surgutneftegaz was expected,” said a source close to the negotiations. “Bogdanov never wanted to be in the project to begin with, because he didn’t want to part with the cash. Now it seems even more is required to get production truly well underway.”

The example set by Surgutneftegaz proved contagious: TNK-BP also informed the other partners of its intention to withdraw.

Surprisingly, Lukoil president Vagit Alekperov suddenly announced his company’s desire to increase its stake in NOC, proposing a buyout of TNK-BP. The reason is not clear, since Lukoil had its own Venezuelan project long before Sechin began cozying up to Chavez.

Nevertheless, the main burden of the Junin-6 project is bound to fall on Rosneft, in addition to which the company will have to fulfill other obligations to Venezuela that were assumed as part of this essentially political deal.

{***Does Russia need oil projects in Venezuela?***}

Does Russia need oil projects in Venezuela?

In October 2011, when Hugo Chavez’s health severely deteriorated (it was reported in 2011 that the Venezuelan president was suffering from cancer), Igor Sechin paid the country a visit. He agreed that Rosneft would acquire a 40 percent stake in the development of the Carabobo-2 block, whose geological reserves are estimated at 5.1 billion metric tons.

In the case of Carabobo-2, Chavez requested even more than for Junin-6. Rosneft paid a bonus of $1.1 billion and issued a further $1.5 billion credit facility to PdVSA on favorable terms. Moreover, the Russian state-owned company needs to build a separate upgrader for the project, since Carabobo-2 oil is also extra-heavy. Project investment is slated at $16 billion, according to Sechin.

To what extent are Russian oil projects in Venezuela economically justified? Troika Dialog analyst Valery Nesterov believes the answer is not clear-cut.

On the one hand, they allow companies to pile up reserves on the balance sheet, and the potential level of production is comparable to the largest projects anywhere in the world. If all indicators prove correct, the profitability of development could be about 18 percent, which Nesterov asserts is “reasonable.”

On the other hand, the analyst warns that the political risks are extremely high.

“Venezuela has great prospects, but there is far too much invested in personal friendships. History is not short of examples of foreign companies’ assets being nationalized by a hostile government,” said a top manager at a Western investment bank.

Russian officials assert that the re-election of Chavez has removed any lingering political risks.

Nonetheless, the situation for the Venezuelan leader can hardly be described as stable. Experts note that, in recent months, Caracas has upped government spending in an overt attempt to assuage the socially disadvantaged – a group that makes up Chavez’s core constituency.

“Officials are essentially burning money to buy votes, so next year you can expect to see an economic slowdown,” Bret Rosen, a Latin America strategist at Standard Chartered Bank, told Bloomberg. He foresees higher inflation and the devaluation of the Venezuelan bolivar.

Two years ago, devaluation, combined with inflation, led to widespread social unrest throughout the country; but Chavez clung on to power. However, back then the Venezuelan leader was not ill with cancer (at least not officially), and his popularity ratings were a good deal higher than they are now.

High oil prices remain the only guarantee of stability in Venezuela. But, as always, the markets are fickle.

The article is abridged and first published in the Kommersant-Vlast magazine. Kirill Melnikov, Alexander Gabuev, Elena Chernenko contributed to the story.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox