Screenshot from 'Ivan, Son of Amir' movie from director Maxim Panfilov. Source: kinopoisk.ru

If there is a film about war—for example, "Circles," from Serbian director Srdjan Golubovich—it has to be a war between Muslims and Christians, with the inevitable attempts to find a path to reconciliation at the end.

Films about love—take the Russian entry, "Ivan, Son of Amir," from director Maxim Panfilov—are about a Russian woman who falls in love with an Uzbek villager. Then there is the Russian guy who loves a young Buryat, as in the Russian film from director Bair Dyshenov, "The Hunter: First Love."

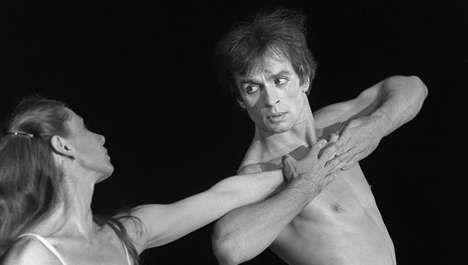

Here, however, some formal rules have been broken, because Buryats are generally Buddhists. If we look at the documentary film "Rudolph Nureyev: A Rebellious Demon" (from director and scriptwriter Tatiana Malova) about the famous gay dancer, there really is no connection to the original concept.

Director Tatiana Malova shooted a movie about the famous gay dancer. Source: kinopoisk.ru

Organizers do not conceal the fact that the festival has become much less Muslim than it was, for example, in the early years of its existence, when it was known as the "Golden Minbar" (an elevated place in a mosque from which the Imam preaches).

According to the artistic director of the festival, Albina Nafigova, the festival should not be seen as a showing of religious movies. Islam here is given the modest role of "cultural entity"—but no more than that. All of the attention is focused on the problems that arise when different cultures and civilizations interact, which is completely consistent with ideology of the festival as expressed in its motto: "From a dialog of cultures to a culture of dialog."

The heads of four international film festivals will come to Kazan to observe this dialog: the head of the Seven Rivers Festival in Italy, Emilio de Lachezi; the director of the Al Jazeera International Documentary Film Festival, Abbas al-Arnout; the Serbian film critic Miroljub Vuchkovich, who was program director of the Belgrade Film Festival in 1997–2010; and the head of the Geneva International Eastern Film Festival, Tahir Houca.

Russian guests that have promised to attend the festival include Vladimir Menshov (representing the film "Courier"), Alexander Pankratov-Chyorny and Dmitry Dyuzhev, who played the main role in the abovementioned "Ivan, Son of Amir."

Screenshot from 'Ivan, Son of Amir' movie from director Maxim Panfilov. Source: kinopoisk.ru

The jury, which is headed by Mosfilm director Karen Shakhnazarov, will be considering 20 artistic films and 20 documentary films—10 full length and 10 shorts for both categories. There will also be 10 animated films in the Young Viewers category. There are an additional 60 non-competing films that will be shown. Critics have already recommended the films in the large non-competing Window to Europe category, which includes French and Hungarian films.

Some other talked-about categories include After the USSR (films from countries of the former Soviet Union), The First Take (debut films of young Russian directors), Indian Cinema, and retrospective films of Shakhnazarov himself.

In 2010, as a result of a conflict between the Tatarstan Ministry of Culture and the Moscow Festival Directorate, the festival was stripped of its Golden Minbar brand name. Then, in fall 2011, a huge scandal erupted at the film festival when the Gran Prix was awarded to a German actress of Turkish origin, Sibel Kekilli—a former star of German porn films.

Russian filmmakers to create ethics code this summer

Some in Tatarstan saw this as an attempt to besmirch the religious leaders of the Muslim republic, who, however, did not have anything to do with the festival picks. For Muslims in Tatarstan, the festival lost its meaning as a Muslim film forum with emphasis on the word "Muslim."

In the opinion of Farid Salman, the president of the Board of Ulamas for the Russian Association for Islamic Unity and director of the Kazan Center for Studying the Koran and Sunnah, the Kazan film festival should now be considered a purely secular event—albeit with some Islamic flavor.

"Personally, I have always found it difficult to determine what constitutes Islamic film,” said Salman. “On the one hand, according to Islamic views, Muslims should not divide the world into secular and religious—in Islam, it is all one. So, if the film was made in a Muslim country, it should objectively be considered Muslim. On the other hand, I cannot call a festival Muslim that shows films that do not correspond to the morality and ethics that Islam teaches, in spite of the fact that they were created in Muslim countries. The program for the current Ninth International Film Festival includes these types of films; therefore, I can't call this forum Muslim. This is a purely secular event."

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox