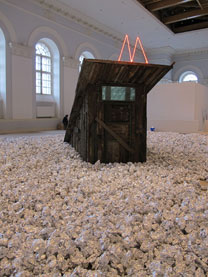

An installation of Canadian Erin Manning. Source: Alexandra Sopova

The main exhibits of the Fifth Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art are located downtown in the Manezh exhibition hall—the largest in the city. In an intricate maze (you cannot see the whole room from any point, and the view of the walls from above is like a Malevich painting), grand-scale and miniature projects coexist, representing a total of 72 artists.

Meetings in Manezh

Some artists found themselves next to others with whom they had never collaborated. A 490-foot wall on the lower level is filled with drawings by three artists. American Mark Licari and Uruguayan Ricardo Lanzarini said that, since they both had Italian last names, the third might as well be a true Italian. So, Biennale curator Catherine de Zegher invited Andrea Bianconi, and the three artists created a composition on the theme of revolution and transformation. Some of its elements are full of anxiety and some are full of humor: A dog turns into a mop, fantastic characters chase each other.

The installation of Filipinos Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, with sleds, skis and boots hurtling after each other, seems to be heading through the wall to the Kremlin.

The installation of Filipinos Alfredo and

Isabel Aquilizan. Source: Alexandra Sopova

Some sleds are centuries-old museum pieces, while others were handmade at end of the 20th century. The simple, factory-made sleds were donated by ordinary people, in response to a request on the Internet.

Everyday art

Chinese artist Song Dong's installation occupies a huge space. He sorted and then fit together thousands of his father's things: worn-out shoes, spent tubes of toothpaste, dishes, stacks of tattered magazines, undergarments and even pieces of foam packaging from household appliances. Song Dong's mother had been collecting them her whole life. By putting all this in a museum, the artist wants to help his mother cope with the pain of losing his father.

Chinese artist Song Dong's installation. Source: Alexandra Sopova

"Song Dong's work is incredibly powerful: It is a metaphor for how our daily lives swallow us up and do not allow us to resist or think about the big picture; it is a look at the world through the lens of daily life," says permanent Biennale commissioner Joseph Backstein. "It is also an attempt to draw a new border between what is art and what is not."

The art of discrimination and ecology

Catherine de Zegher, the first female curator of the Moscow Biennale, has said that she does not consider projects dedicated to short-term political upheavals to be worthy participants. However, this does not mean the exhibition is completely politically apathetic.

"The Biennale is politicized and reflects the feminist leanings of the curator. For example, the artist Umida Akhmedova from Uzbekistan was invited. She photographs Middle Eastern girls with their mothers-in-law and invites the viewer to speculate on the relationship between the generations of women in the family," says Backstein.

Incidentally, this year the Biennale hit the 50/50 ratio for the first time—a full half of the participants in the exhibition are women.

Projects devoted to the problems of aboriginal peoples also found a place at the show. Australian artist Richard Bell presented his work from the famous “Bell's Theorem” series. At the top of his abstract painting are the words: “The first shall be last, and the last the first.” Aboriginal issues are also the theme of the piece “Three Rivers” by Australian Lorraine Connelly-Northey. The installation made of rusty pieces of iron is meant to represent those who do not have access to clean water.

The art of Irishman Tom Molloy is devoted to the nature of rallies and demonstrations: People holding signs for or against some position are mixed together in his installations. Likewise, viewers can feel like they are participating in a Canadian political rally when standing between screens of the installation “Round Dance” by American Alan Michelson.

Ethiopian Julie Mehretu, who now lives in the U.S., created her work “Beloved” based on the recent events in Cairo. The situation in Iran is the subject of a wall painted with ornamental butterflies. The parents of the Iranian artist Parastou Forouhar were prominent members of the opposition and were brutally murdered in 1998. The artist created butterflies dedicated to the memory of her parents: If you look closely, you can see that each one is actually a dismembered body or a woman who is crouched down and weeping. The name of the artist's mother means "butterfly" in Arabic.

Utopia and reality in the same room

A classic at the Biennale is the airship of the Belgian artist Panamarenko (an acronym from the name Pan American Airways and Company) that has been flying through museums of the world since 1969. The artist is famous for his utopian flying machines.

|

| “Plowed Field” by Russian artist

Alexander Brodsky. Source: Alexandra Sopova |

Next to the airship is Russian artist Alexander Brodsky’s “Plowed Field,” which is a battered wooden entrance to an unknown place with a sign of the Moscow metro. Volunteers crushed tinfoil for three days for this installation.

On the lower level, there is more modern art: here, Mona Hatoum hung a cobweb made from glass spheres that will reflect what is happening in the Biennale. Polish artist Gosia Wlodarczak from Australia drew with white marker all over the transparent surfaces on the ground-level hall. She captured everything that she saw around her, even faces of the employees and auxiliary structures. All of the artist's lines are of the same thickness, because all events are equally important—this is how she reflects reality.

"Each era—Romanticism, Modernism, etc.—has its own model of the world, including space-time," says Backstein. “Today, there is no one style that dominates, and so artists are investigating the different spatial, temporal and even daily circumstances of, not the glamorous world, but everyday life. It is not just a European trend. There are many Asian artists here, and each one is presenting his model of the neo-capitalist world. What is represented here is a possible model for the world. Crowds of people have poured into the exhibition. The public comes with no expectations or prejudices; they are prepared for absolutely anything.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox