Tsarevich Alexei (in the centre) with his teachers, Gibbs is second from right. Source: ITAR-TASS

Faith and church have always been a point of cultural and spiritual gravitation for many Russians abroad. The sense of community, so deeply embedded in the Russian national character, is nurtured by the spiritual experience shared with fellow believers, and helps many to feel more at home when they are abroad.

This year both Orthodox and Catholic churches celebrate Easter on 20 April, symbolically reuniting Christians around the world for the holiday. This is a good opportunity to recall that England was once Orthodox, its population converted by the first Christian missionaries in the 7th century. The Norman Conquest ended almost 500 years of English Orthodoxy after Duke William of Normandy, blessed by Pope Alexander to bring the English Church under the control of the Roman Papacy, triumphed over King Harold II in the battle of Hastings in 1066, a battle that Harold did not survive.

Today, faith-related links might not be the first thing to come to mind in the context of Russo-British cultural relations, but one Englishman spent his life making them a reality after being part of one of the most tumultuous chapters in Russia’s 20th-century history.

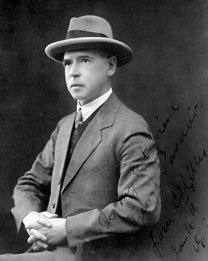

|

| Sir Charles Sydney Gibbes. Source: angelfire.com |

Sir Charles Sydney Gibbes, born in 1876 into the family of a bank manager in Rotherham, near Sheffield, studied at Cambridge (where he returned to his surname Gibbs its original spelling – Gibbes) and contemplated English priesthood as a future career. His biographers point out that behind the self-restrained, cultured and gentlemanly Victorian veneer there was a man of spiritual sensitivity, instinctively searching for something he could not find in the Anglican Church.

It may have been this search that drove Gibbes eastwards in 1901, to imperial Russia, with which he had no connection. He managed to build a profitable reputation with the upper crust by teaching English to the children of a couple of noble Russian families, and in 1908 Tsarina Alexandra invited him to St. Petersburg to improve the English language skills of the Grand Duchesses and Tsarevich Alexei.

Eventually the boy, who was suffering from a grave illness, became the key focus for Gibbes. He treated Alexei with great devotion and patience, which was not easy: The boy “could be influenced only by his feelings, and would not yield to authority. He submitted only to the emperor.” The whole Romanov family – very closely knit, pious and reverent – seemed to embrace the English tutor in a circle of trust and respect. The children called him “Sidney Ivanovich”, and he confessed that “in regard to their attitude towards each other, this was an ideal family, very rarely met with. They did not need the presence of other people.”

The Romanovs so inspired him with affinity and spirituality that Gibbes refused to leave them in the terrible days of captivity after the revolution and followed them in 1917-1918 as they were moved first to Tobolsk and then to Yekaterinburg. Fascinated by the humility and courage which the Imperial family found in faith, he was ready to share their lot as his own.

However, Gibbes, along with a number of other servants, was not given access to Ipatiev House, where the family was being kept, and did not get a chance to see it until after the tragedy of 17 July 1918, when the Imperial family was massacred by the Bolsheviks.

The mementoes he collected then, things that used to belong to the family, Gibbes would cherish as sacred until the end of his days. Anxious to learn what happened that night, he also took part in the investigation carried out while Yekaterinburg was under White Army control.

In his testimony, Gibbes gave a detailed and emotional account of his life with the Romanovs right up until the last day, along with a description of each of them, which gives away how much of a personal loss it was for him.

He admired the Tsar and Tsarina’s devotion to each other: “They were an ideal couple and never separated. My opinion is that it would be hard to meet, especially in Russia, such a devoted pair who missed each other so much when they were parted,” he said.

Pointing out the spiritual unity of the Romanovs, he highlighted that Alexandra “was most devoted to her family and religion entered into her feelings immediately after the family,” while Nicholas II “loved his country devotedly and suffered for it greatly during the revolution. After the Bolshevik Revolution it was felt that his sufferings were not due to his situation but that he suffered for Russia.”

The seizure of Yekaterinburg by the Bolsheviks cut the investigation short, but Gibbes found his own way to preserve his link with the Imperial family.

Deeply moved by the crime as well as the refusal of the Romanovs’ relatives in the British Royal family to offer asylum to them, he moved on to China, where he spent almost 20 years. The shock and mourning of the previous years, as well as his own grave illness, must have had a deep emotional effect on Gibbes, for in 1934, in Harbin, he joined the Russian Orthodox Church, taking the name of Alexis, after Tsarevich Alexei.

Charles Sydney Gibbes and Grand Duchess Anastasia, the youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II. Source: angelfire.com

He then became successively monk, deacon and priest, taking the name Father Nicholas, after Tsar Nicholas II. In March 1935 he was ordained Abbot, becoming the first English Orthodox abbot in history. But for Father Nicholas, Orthodoxy was also very personal, as deeply cherished as the dear memory of the Imperial family who had inspired him so much with their own lives – both as the rulers of Russia and as humble prisoners. The martyrdom of the Romanovs had paved the way to this dramatic change in his own life.

Gibbes’s biographers describe the conversion in his own words as “getting home after a long journey.” Indeed, shortly after, in 1937, Father Nicholas returned to England for good with the hope of establishing an English-language Russian Orthodox parish in London, an endeavor in which he was not successful.

In 1941 he moved to Oxford, and a few years later he set up a chapel dedicated to St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker inside his own new home at 4, Marston Street. There he put on display many of the objects rescued from Ipatiev House: The chandelier from the Grand Duchesses’ room lit the chapel, the Tsar’s boots stood by the altar, and the icons – some of which had been gifts from the family – were put up on the walls. The mixture of deep Orthodox belief and the personal cult of the martyrs must have been quite striking for the congregation of the time.

Archimandrite Nicholas died in 1963, but after so many years his presence is still felt. The first Russian Orthodox community in Oxford he founded was given a new start in September 2006 when the Russian Orthodox Parish of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker was formally re-established.

In 2010 it found a home in a former Anglican church, ironically just off Marston Road, and still quite close to 4, Marston Street, its historical home. The latter address, St. Nicholas House, is now just a block of flats, and according to Father Stephen Platt, the rector of today’s Church of St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker, a couple from the parish found a place there just after they had moved to Oxford and were desperately looking for a home.

Platt says that the parish is quite small and international (just about 40 percent are Russian) embracing people with very different backgrounds who together form a closely knit community where everyone is family. “The choir is certainly amateur,” he admits, “but so sincere!” Interestingly, he adds, the wife of one of Father Nicholas’s first spiritual children now sings in this choir.

This church and its parish know their roots well. The icons are a selection of Russian and ancient British saints, like St. Alban and St. Frideswide (the patron saint of Oxford), who learned the ways of monasticism from the first missionaries of the Orthodox East. This interaction is reflected in the history of the English Church and people by the Venerable Bede, the English chronicler, whom Father Stephen likens to Russia’s Nestor: “Through their works we can trace the formation of the identity and faith of our peoples in the early days.”

You won’t find the belongings of Father Nicholas or the imperial possessions in this church: After Gibbes’ death these were given to a museum at Luton Hoo by George Paveliev, his adopted son. The collection was later moved and made part of the Wernher Collection in Greenwich (run by English Heritage) but is no longer part of the collection. Annie Kemkaran-Smith, a curator for art collections in London at English Heritage, says that the Gibbes collection is now “privately owned and not available to view by the public.”

This makes Father Nicholas’s possessions hard to trace, though it can be hoped that they will reemerge some day at a private exhibition. In the meantime, a year after the 400th anniversary of the House of Romanov and in the year officially devoted to a celebration of the cultural links between Russia and the UK, a more important thing to bring back into the light is this story of how one man linked countries, cultures and peoples through his faith. Sir Charles Sydney Gibbes truly found the calling he had been searching for, and what an exceptional one it was.

For more information about UK-Russia Year of Culture visit The Kompass, special RBTH section for all UK-Russian cultural events

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox