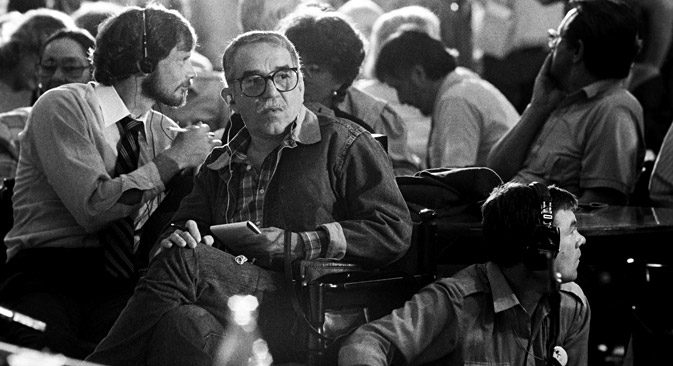

Gabriel Garcia Marquez on the XV International Film Festival in Moscow in 1987. Source:. M. Yurchenko / Ria Novosti

Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez, winner of the Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature, has died in Mexico at the age of 87. Sergei Markov, translator of his memoirs and author of his first Russian biography, published in 2012, talks about his meetings with the Colombian writer and his connections with Russia.

Unlike most translators, you have had an opportunity to meet with the writer personally. Can you remember in what year and under what circumstances this happened?

The first time I met Marquez was in Havana in 1980, when I interviewed him for the [Soviet] magazine Ogonyok. He asked, “Why such a strange name?” Ogonyok in Spanish is fuegito (“little fire”). “Yes, but what does that matter, please answer the question about the novel, about creativity,” I asked. And he answered: “What do you mean creativity; you explain what this ‘fuegito’ means.” Then it took me ten minutes to explain the name to him. It became the funniest interview.

Outwardly, he seemed to be like our artist [Armenian actor] Armen Dzhigarkhanyan. A charming man who knows how to win people over – a pat on the shoulder, the telling of an anecdote or a steamy joke. During his life, Marquez gave interviews in the thousands, perhaps tens of thousands. And each time he talked about himself differently. He mythologized everything he could. He even gave different dates of his birth. That is why everyone was waiting so much for the appearance of his memoirs. We all waited, to see, at last, what the final official version of his life would say. All his works are imbued with autobiographical motifs. Marquez grew up in the town of Aracataca, this is Macondo from One Hundred Years of Solitude.

You called your book The Whores and Dictators of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Is this a metaphor or are you talking about real harlots and real dictators?

Remember, in the Holy Scriptures there are almost no positive heroes. Even the apostles have an ambiguous attitude – while the whores are all positive: Mary Magdalene, Mary of Egypt. With Marquez, it is the same thing. This line can be traced from his early narratives, with the story entitled The Woman Who Came Precisely at Six, about a prostitute who killed a client. Marquez justifies it – as she could not but kill him.

The subject of harlots is present in all his works up to the Memories of My Melancholy Whores. In an interview with the U.S. magazine Playboy, he said, “Prostitutes have always been my best friends”. He lived in brothels, which were cheaper than hotels. Prostitutes ironed his shirts and reprinted his manuscripts. In his memoirs, he describes how one prostitute, naked and wearing glasses, was sitting and typing his story. They told him stories and even criticized his works.

No less was his interest for dictators. Upon arrival in Moscow, Marquez immediately went to the mausoleum, where Stalin was lying at that time. He scrutinized the mummy and drew attention to the hands, which seemed to him feminine. He later attributed this trait to his dictator in the Autumn of the Patriarch. The image of the patriarch is complex; it is similar to a mosaic, containing features of different people. Marquez took the eyes from one person, the manner of speaking from the other. When he lived in Barcelona, he had an opportunity to meet with Franco. Marquez refused: “What would I tell him? Would I have to tell him that I was writing a book about a son of a bitch and I would like to give him your features?”

Marquez’s Russian fate began in the 1970s. He immediately became wildly popular. Since then, everything connected with Latin America has been causing a massive stir in Russia, even soap operas. Why do you think this is so?

We are similar to the Latin Americans in our laziness, openness, and even in our severity. Both Russia and Latin America tend to share the feeling of an epic, of belonging to great history. “The most interesting people live in the Soviet Union,” Marquez always said. One of the Soviet readers copied One Hundred Years of Solitude by hand. Then she explained this act by saying: “I wanted to know which one of us was crazy, him or me.” The creation of Marquez with his whores and dictators was a revelation to us. It is amazing how they even published him.

Presumably, it is due to his communist views.

Of course. You have to remember that he had been friends with Fidel Castro since 1948. Cuban dissidents told me that Fidel financially supported Marquez’s popularity. And Fidel meant the Soviet Union and petrodollars. He visited our country about fifteen times.

The first time he came to the Festival of Youth and Students, spent one month here and wrote an extensive essay titled “22,400,000 square kilometers without a single Coca-Cola advertisement”. Then he came in the time of Gorbachev, by his personal invitation. He visited the editorial office of the Soviet magazine Ogonyok and met with the stage director Spesivtsev, who at that time was staging “One Hundred Years of Solitude”. He put on makeup and began to show the actors how to act. And then suddenly, he stopped coming and taking an interest in our country. There was a great tragedy in his life, as he himself said – the collapse of the Soviet Union. After 1991, Russia no longer presented any interest for him.

Originally published in the Ogonyok magazine.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox