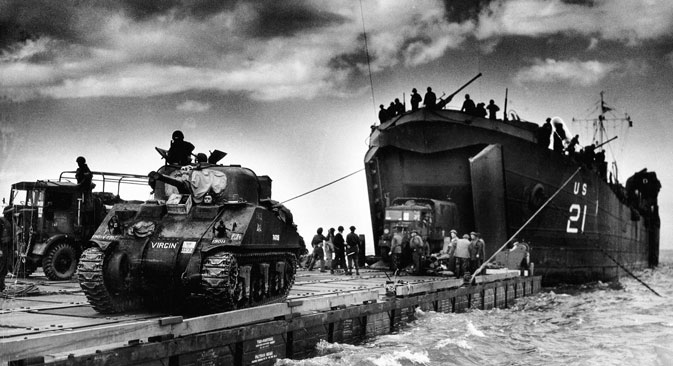

The U.S. Coast Guard manned USS LST-21 unloads British Army tanks and trucks onto a "Rhino" barge during the early hours of the invasion on Gold Beach. 6th June 1944. Normandy, France. Source: Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock_photo

On June 6, 1944, hundreds of thousands of Britons, Americans, and Canadians landed in Normandy in the largest amphibious operation in history, becoming brothers in arms with the Soviet soldiers who were locked in savage fighting on the Eastern Front.

But at that moment, when millions in Europe were sacrificing their lives in the struggle for what they believed in, a game of deceit was unfolding in government offices in Moscow, London, and Washington. Europe was at stake, and possibly the whole world as well.

The second front was created amidst a complex geopolitical game in which the Allies looked far ahead and, even at the beginning of the war, were trying out the new post-war world roles for their states. Before the war, the Soviet Union and the West were, if not enemies, then at least antagonists.

Landing of the allied forces in Normandy. Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock_photo

There were no illusions

that peace would reign after the victory over the common enemy, but the harsh

military reality continued to dictate its own terms.

Bearing the brunt

On June 22, 1941, the Soviet Union was essentially fighting a war not only with Germany, but with most of Europe, not to mention the fact that Turkey and Japan could have joined in at any moment.

Britain and the U.S., whose politicians had criticized the USSR almost as much as they had Hitler’s Germany in their speeches before the war, were aware that the Soviet Union was instrumental in their fight against the Axis Powers.

On June 6, 1944, hundreds of thousands of Britons, Americans, and Canadians landed in Normandy. Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock_photo

Joseph Stalin first brought up the issue of a second front on July 18, 1941. First, he suggested to Churchill to "drop 25-30 divisions in Arkhangelsk or transfer them via Iran to the southern regions of the USSR," or to use aircraft from airfields in the Crimea to destroy the center of the Reich’s petroleum supply – the Romanian oil fields in Ploiesti.

London and Washington hesitated when it came to the issue of providing aid to the USSR, not only due to their rejection of the Communist regime, but also because of the fact that a blitzkrieg in Russia could have achieved the same results as the one in France.

As "official" English historians Butler and Gwyer point out, "no one wanted to lose valuable military resources in the chaos of the crumbling Russian front when these resources could be used in any other place." On November 6, Churchill told Anthony Eden, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who was on his way to Moscow, to not “make any promises.”

The second front postponed

But things changed in December. It became clear that the blitzkrieg against Russia had failed. Moscow, London, and Washington were negotiating until May, which resulted in the USSR’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov traveling to England and the United States, where treaties were signed to form an alliance in the war against Nazi Germany and its allies in Europe.

Molotov needed guarantees of a second front, which he was able to obtain from Roosevelt. In London, however, when the Commissar asked to "involve at least 40 German divisions in battles with Western Europe," Churchill evaded giving a direct answer.

According to British historian R. Parkinson, Roosevelt’s promise also turned out to be unreasonably optimistic. That same day, on June 1, the British Chiefs of Staff Committee spoke out against the plan to invade across the British Channel in 1942. On July 23, Stalin stated in a letter to Churchill that the issue of a second front in Europe was beginning to take on a "frivolous character."

Star-crossed lovers found each other 60 years after wartime romance

It should be noted that the retreat of the Soviet army in the summer and fall of 1942 made the possibility of aid from the Allies even less likely, not more. Doctor of Historical Sciences and Soviet Ambassador to Germany (1971-1978) Valentin Falin described the West’s attitude toward the USSR as follows: "The only thing the Allies did was discuss concerns: how to not miss the moment of truth when the Third Reich begins to lose ground, how to ‘hinder the Bolshevization of Europe’."

By the end of the Anglo-American conference in Casablanca, it became clear that in fact the opening of a second front would be postponed until 1944.

The preparations of the Allies in the Mediterranean and their subsequent landing in Sicily changed little for the USSR. After mobilizing all its forces and means, Nazi Germany launched a third summer offensive against the Soviet Union in Kursk on July 5, 1943. Stalin recalled and then replaced the Soviet ambassadors in Washington and London.

Professor Oleg Rzheshevsky, Doctor of Historical Sciences, who took part in the war himself, notes some consistency in the actions of the Allies: "History repeats itself. In anticipation of the next Wehrmacht summer offensive, the Allies announced the postponement of the second front.

Supplies of military equipment to the USSR were reduced, or even stopped completely. This was in 1942, and the same thing happened in 1943. The conclusions drew themselves."

Concession

The events that unfolded during the summer and fall of 1943 on the Soviet-German front dramatically changed the entire military and political situation. It became clear that Germany was doomed and that the USSR was capable of achieving victory on its own. The decision to launch a second front was made on November 28,1943 at a conference in Tehran.

From 1943 onwards, the leadership of the USSR regularly received intelligence reports about secret contacts between the German opposition and the U.S. and Britain. The Battle of Kursk was still going on when Roosevelt, Churchill, and their closest advisers allegedly discussed the following question during the negotiations in Quebec: Would the Germans “help” Western military forces enter Germany in order to assist in the fight against the Russians?

Operation Rankin was approved, along with the plan for a landing in Normandy, Operation Overlord. Rankin was based on reaching an agreement of non-resistance of the Wehrmacht in the case of the Allied landings with the disaffected German elite. At the same time, it would allow the USSR to occupy a significant part of Europe a lot sooner.

On May 24, 1944, the U.S. Department of State informed the Soviet Embassy in Washington that "two emissaries of one German group recently approached the American representatives in Switzerland with a proposal to overthrow the Nazi regime.”

This was a warning to Moscow that the Western powers had a fallback option for ending the war with Germany that would be developed if the USSR would not learn to respect the wishes of its allies.

The plan came to a halt

when Claus von Stauffenberg unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Hitler. The

Reich began a compulsive cleansing of the army and all government agencies of people

involved in conspiracies and dissidents. The Western Front’s backup plan did

not pan out while the Fuhrer was alive.

The second front

Opening a second front did not end the controversy, but it did accomplish the main goal. Fascism was defeated and order was restored in the world, albeit with a "Cold War" backdrop.

Could the USSR have defeated Germany without the help of the Allies? One of the most famous and popular modern Russian military historians, Alexei Isayev, claims that it could have.

"Indeed, the Red Army could have pressed on, and it is unlikely the Germans could hold it back. But, nevertheless, the losses would have been much larger." Although it came late, Western aid probably saved hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers.

"The allied soldiers carried out their duty honorably. Their contribution to the defeat of Nazism is not detracted by Churchill’s escapades or Roosevelt’s behavior.

“Everyone who supported the Soviet people in combat with the Third Reich with solidarity, supplies of food, medicine, weapons, and vehicles deserves appreciation." This assessment of the second front’s contribution by Doctor Falin is, in our opinion, the most accurate summary of what happened 70 years ago.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox