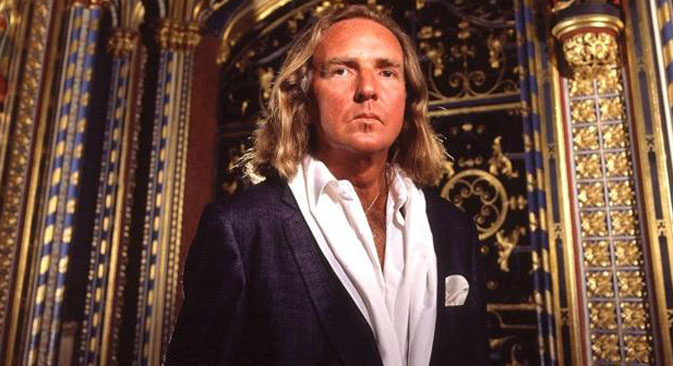

Taverner's music was influenced by Russian culture. Source: Press photo

Sir John Tavener described his compositions as an “icon in sound”: a shimmering, ecstatic contemplation of the divine, the musical equivalent of Orthodox painting. In a career that ranged from singing with the Beatles to memorialising Princess Diana, Russian culture was Tavener’s most enduring influence. But he never made it to the country whose faith, music and literature inspired his work until his death last year at age 69.

A festival at the Moscow State Conservatory was to have marked Tavener’s first visit to Russia, said Professor Konstantin Zenkin, the chairman. Running from September 21-23, “From Taverner to Tavener: Five Centuries of English Sacred Music” will now be a celebration of the work of a man for whom Russia opened the door to a diverse tableau of sounds and beliefs.

“Tavener deeply grasped the style of Russian and Greek sacred music, believing that they preserved the spirit of ancient Eastern Christianity, the spirit of Byzantium,” Zenkin said.

Orthodox ‘homecoming’

Tavener was an idiosyncratic figure—a devout mystic who also collected vintage cars, loved fine wine and recorded on the Beatles’ Apple label (thanks to an early meeting with John Lennon, with whom he swapped music). “Despite his music often being quite challenging in formal terms, he was able to produce work that connected with a huge number of people,” said music critic and composer Sean Martin.

While studying at the Royal Academy of Music, Tavener idolised the work of Igor Stravinsky. The admiration was shared: When Stravinsky came across an early score of Tavener’s, he simply wrote “I know” across the top of the page.

Early works such as “Ultimos Ritos” (1972) were inspired by the Catholic faith. After meeting figures such as Metropolitan Antony of Sourozh, however, Tavener turned to Orthodoxy, to which he converted in 1977. “Orthodoxy gave Tavener a sense of direction and renewed his creative fires at a time when he greatly needed both,” Martin said. “He described his conversion as a homecoming.”

Initial experiments with Russian culture included “A Gentle Spirit” (1977), based on the Dostoevsky story, “Six Russian Folk Songs” (1978) and “St. John Chrysostom,” a liturgical piece that got a lukewarm reception at its London debut in 1977.

Akhmatova’s ‘Requiem’

Tavener’s first major piece to be profoundly influenced by Russia was “Akhmatova: Requiem” (1980), which the composer described as “one of the peak achievements of my middle life.” Ivan Moody, a British composer and Orthodox priest who studied with Tavener in the 1980s, said that the “magnificent” piece marked the apotheosis of Tavener’s relationship with Russian Orthodoxy.

“Though it is not a liturgical work, Tavener's approach to the poetry was spiritual, and for that reason, to Akhmatova's ‘Crucifixion’ poem he added two liturgical prayers in Slavonic,” Moody said. “The use of the deep bass voice and tolling bells adds to this evocation of the Russian Church.”

At the time of the 1981 premiere, Akhmatova’s work was still banned in the Soviet Union; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, who came to London to conduct “Requiem” at the Proms with the BBC Orchestra, was warned by the KGB not to perform it. Rozhdestvensky went ahead with the piece, whose score he was forced to hand over to the authorities upon returning to Moscow. (It would be performed in that city eight years later during perestroika, to great acclaim).

Icons in sound

Tavener’s interest in Orthodoxy deepened in the early ‘80s thanks to Mother Thekla, a nun who became his spiritual guide. He wrote the “Akathist of Thanksgiving,” which premiered at Westminster Abbey in 1988, using her translation of a poem by Orthodox priest Georgy Petrov, written in the 1940s in the labour camp where he would perish. “Musically, it is cold and dispassionate—icy, almost—but the libretto glorifies life in all its aspects,” Martin said, with the phrase “glory to God in everything” repeating throughout.

Under Mother Thekla’s influence, Tavener wrote some of his most successful “icons in sound,” including “The Protecting Veil” (1987). She also provided the text for “Song for Athene,” a simple, moving piece that became Tavener’s most popular work after it was played at the closing of the funeral for Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997.

In the last two decades of his life, Tavener gradually moved away from Orthodoxy into a new Universalist phase. He began incorporating sounds and instruments from a diverse array of faiths and cultures, including Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism. He also started using non-Western instruments such as Tibetan horns.

Tavener’s interest in Russian culture re-emerged in his final years. In 2012, he wrote “The Death of Ivan Ilych,” based on Tolstoy’s novella. Martin was present for the premiere in Manchester last summer. “I was struck by how formidably dark and technically difficult the piece seemed—a very far remove from the consoling simplicity of ‘Song for Athene,’” Martin said. “Given the plot of Tolstoy’s story, it also seemed like a premonition of Tavener’s own death a few months later.”

Tavener in Moscow

Though Tavener never made it to Russia, Zenkin said the upcoming festival has been organised in accordance with his wishes. Tavener’s work is already studied by Russian musicologists and mentioned in the press, he said, but the festival, organised by the British Council, represents an opportunity to popularise it among the Russian public.

The Tallis Scholars and the Intrada Ensemble, under the direction of Peter Phillips, will perform Slavonic text arrangements, English-language compositions such as “The Lamb” (based on William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence”) and the Russian premiere of “Requiem,” a 2008 piece for cello, soloists, chorus and orchestra that draws on the Koran, Sufi poetry and the Catholic mass.

Though Tavener’s music was deeply spiritual, the composer was always open to a multitude of views.

“I think what impressed me above all,” Moody said, “was the sheer openness with which he would discuss theological questions at any time—the way in which he would discuss the Holy Spirit and, say, Dame Edna Everage, whom he enjoyed very much, almost in the same breath.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox