The year is 1654. Plague rages in Russia; furthermore, a total solar eclipse occurs in the same year. The devout priest, Avvakum, perceives these as God's wrath for the church reforms of Patriarch Nikon, whom he regards as an apostate. Avvakum preaches against the reforms and becomes one of the leaders of the Raskol - the splitting of the Russian Orthodox Church and of the Old Believer movement. He is thrown into prison, from where he begins to tell his story...

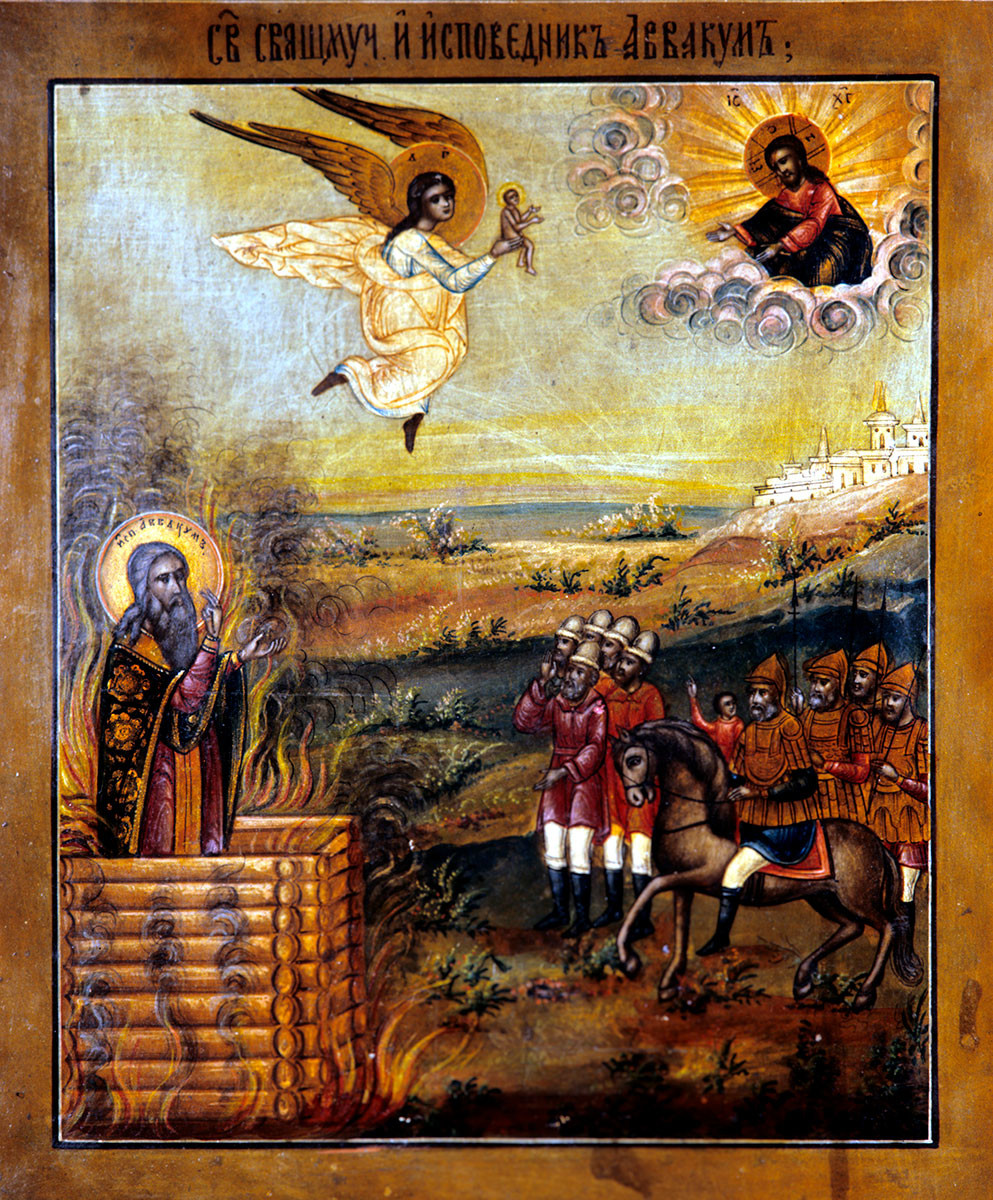

An icon of Saint Avvakum from the late 17th - early 18th century

State Historical MuseumThe future literary author Avvakum Petrov was born in a village in the Nizhny Novgorod Region into the family of a priest. In the Life he writes that at the age of 21 he became an assistant priest (deacon) and, by the age of 31, had "risen" to become an archpriest (protopope), which was quite a senior rank in the Russian Orthodox Church. Even Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich knew and respected him.

Avvakum was an active campaigner against injustice and defended those who needed protection. As a result, he often ended up in trouble, crossing the path of influential people. Once he refused to give his blessing to the son of a noble boyar, and on another occasion he rescued an orphan girl from the attentions of a local "senior official". Avvakum was castigated and beaten, and one day his house was even attacked.

He fled from his persecutors to Moscow, where a church reform had just begun. Patriarch Nikon had just introduced a number of changes to church practices, including a prescription for Orthodox Christians to make the sign of the cross using three fingers, not two. Avvakum responded to the changes with anguish and watched in horror as Nikon forcibly enacted the new rules and severely punished those who disobeyed. The latter were thrown into prison and some particularly devoted monks had their fingers and tongues cut off.

Old Believer Boyarina Morozova's arrest scene pictured by Vasily Surikov, 1887

Tretyakov GalleryFor his refusal to use three fingers when making the sign of the cross and for preaching against the reforms, Avvakum was exiled to Siberia for several years. Subsequently, he was allowed to return to Moscow in the hope that he’d accept the reforms. The Tsar himself came to persuade him, but Avvakum was adamant. Further attempts to get him on board with the reforms were abandoned and he was thrown in prison, from where he began to tell his story.

Pyotr Myasoyedov. The Burning of Protopope Avvakum, 1897

Museum of the History of Religion, St. Petersburg, RussiaWhile in prison, Avvakum continued to preach, and so he and his companions were executed: They were burned alive in 1682.

Old Russian literature effectively traces its roots to the genre of the biographical "life" (vita). A description of a saint’s life would be compiled after his death by monastic chroniclers, following precise rules laid down by the church. They would narrate how piously the saint had lived and what miracles he had performed. Avvakum's Life is different if only because it was written during his lifetime and by the subject of the biography himself. At the same time, the text is vividly dotted with actual names, locations and detailed descriptions. Avvakum also mentions miracles - at the end, he lists the times when he had healed individuals and delivered them from demons.

Sergey Miloradovich. Avvakum in Siberia, 1898

Museum of the History of Religion, St. Petersburg, RussiaAnother innovative feature of Avvakum’s story is that he writes a great deal about his own feelings, sinful thoughts, mental torments and doubts. For instance, he describes how a young woman came to him and confessed her wanton behavior, and how this ignited within himself a lecherous spark ("I was afflicted myself, burning inwardly with a lecherous fire"). He naturally overcame it. Much later, Leo Tolstoy described similar mental torments in his diaries and also in his prose - for instance, The Kreutzer Sonata.

Avvakum's Life is also a polemic. The archpriest gives his views on the most diverse aspects of faith and life; he debates with other priests and sets out arguments against Nikon in defense of the "old" beliefs.

In his A History of Russian Literature published in English in the early 20th century, Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky writes that Avvakum not only ranks among the leading Russian writers, but that no one has since surpassed him "in the skillful command of all the expressive means of everyday language for the most striking literary effects".

The standard view is that the Russian literary language that we still use in speech and in writing to this day was shaped by Alexander Pushkin. Before him, an "elevated style" was employed in literature - words and phrases that were not encountered in the spoken language. Avvakum, however, was the first to use colloquial language in written texts.

Protopope Avvakum. Reproduction of the icon from the Pokrov Cathedral at the Rogozhsky Cemetery of Old Believers'.

Vladimir Vdovin/SputnikThe archpriest starts his narrative by apologizing for his intention to express himself with utmost simplicity: "I love my native Russian tongue and I am not apt to adorn my speech with philosophical verses." He even combines vulgar speech with musings about faith and references to Christ. Here, for example, is how Avvakum describes a mentally unbalanced guard who comes into his cell: "I cropped his hair and washed him and changed his clothes—there was no end to the fleas. I was locked up with him, the two of us lived together, and the third present with us was Christ and the most immaculate Mother of God." And in the next sentence he says that the guard was soiling himself.

The archpriest is also capable of expressing himself in a lofty manner, particularly when writing about people who have suffered for their faith. In his description of human misery, such as the hunger and hard labor of convicts, he becomes altogether poetic. "The river was shallow, the rafts heavy, the guards merciless, the cudgels big, the clubs knotty, the knouts cutting, the torture savage—fire and the rack!—people were starving".

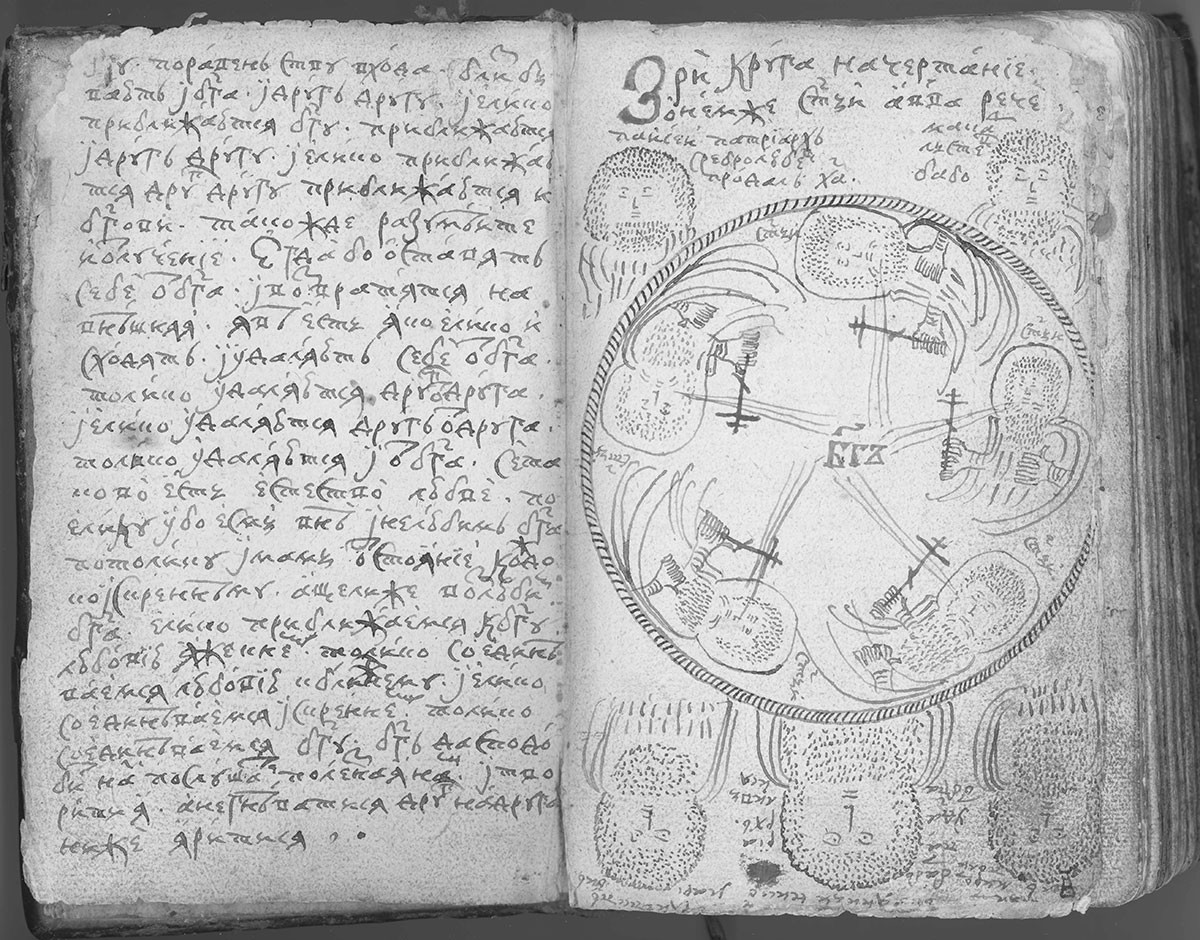

Avvakum's manuscript

The Institute of Russian LiteratureHis Life was banned and it circulated only among Old Believers in manuscript copies. Its first appearance in print only came as late as 1861. Remarkably, this was when Dostoyevsky was writing his Notes from the House of the Dead.

Many saw Avvakum as crude and unrefined, but everyone was full of admiration for his language. "There it is - living Muscovite speech!" wrote Ivan Turgenev. Leo Tolstoy read extracts from the Life to his family, praised the dissenter Avvakum and called him an "excellent stylist". Fyodor Dostoyevsky also rated him highly. In his Diary of a Writer, he propounds that his language is "indubitably multifarious, rich, multifaceted and all-encompassing", and that it would be impossible to translate Avvakum's work into any foreign language - "it would result in gibberish".

Despite Dostoyevsky’s urging, the Life has been translated into English several times. The latest translation, by Kenneth Brostrom, came out in the Russian Library series in summer 2021 Columbia University Press.

Archpriest Avvakum. The Life Written By Himself

Columbia University PressThe publishers describe it as one of the most important works of Russian literature because its "colloquial Russian, its language and style served as a model for writers such as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Gorky". The latter, whose protagonists seem to have come out of the pages of Avvakum's Life, pretty much regarded the schismatic cleric as the first Russian revolutionary. "The language as well as style of the Archpriest Avvakum's letters and his Life remain an unsurpassed example of the ardent and passionate speech of a fighter."

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox