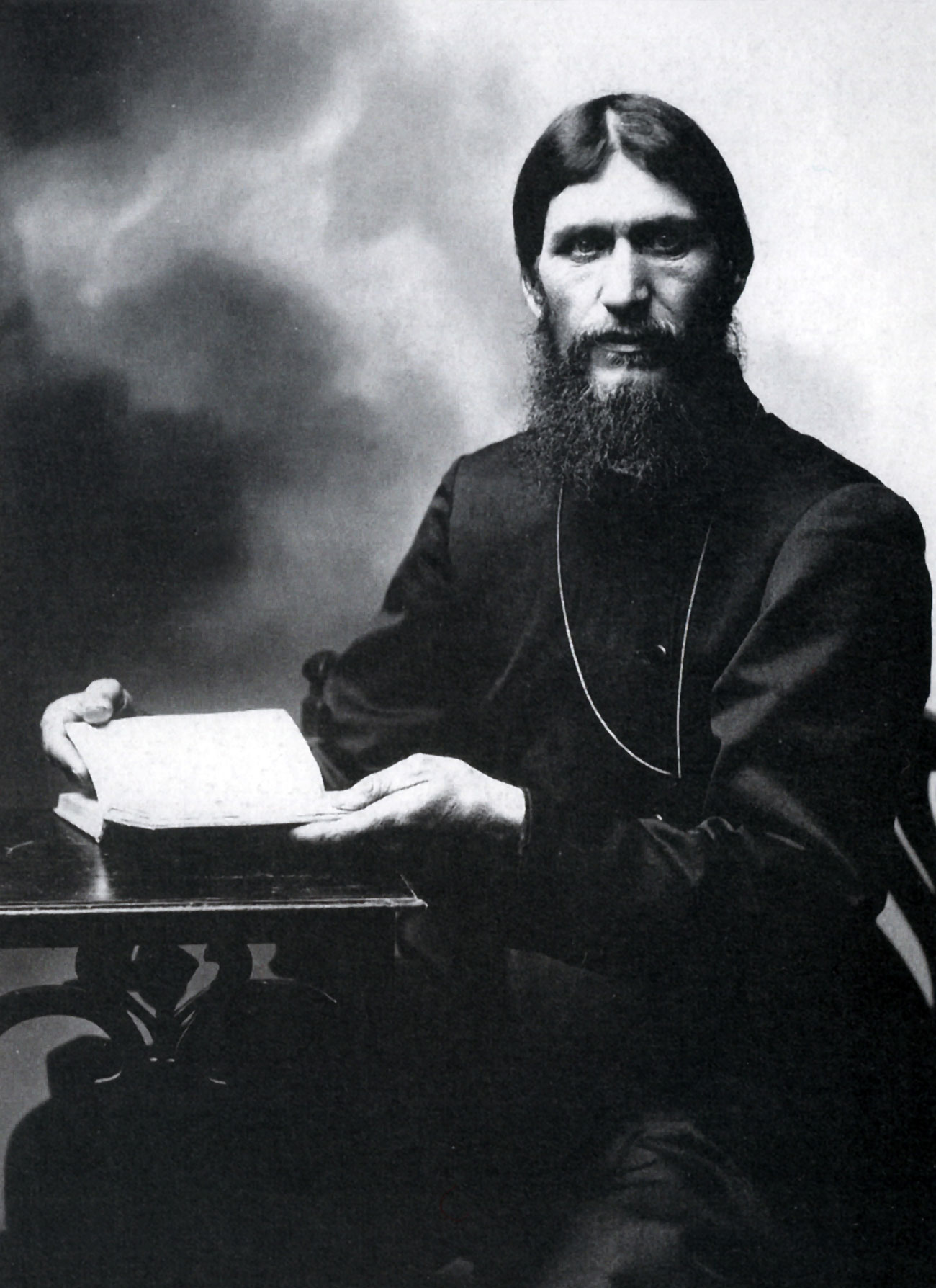

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869 – 30 December 1916) Russian peasant, mystical faith healer and private adviser to the Romanovs.

Photoshot / Vostok-Photo Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869 – 30 December 1916) Russian peasant, mystical faith healer and private adviser to the Romanovs. Source: Photoshot / Vostok-Photo

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869 – 30 December 1916) Russian peasant, mystical faith healer and private adviser to the Romanovs. Source: Photoshot / Vostok-Photo

One hundred years ago, in December 1916, Grigory Rasputin was murdered at the home of Felix Yusupov and his body dumped in the river. Over the intervening century, the story of his unexpected rise and dramatic death has been retold so many times it is now the stuff of legend. Yusupov, during the hideous and prolonged murder, became convinced that Rasputin was “the reincarnation of Satan himself”. But a new biography by award-winning historian Douglas Smith examines the man behind the myth.

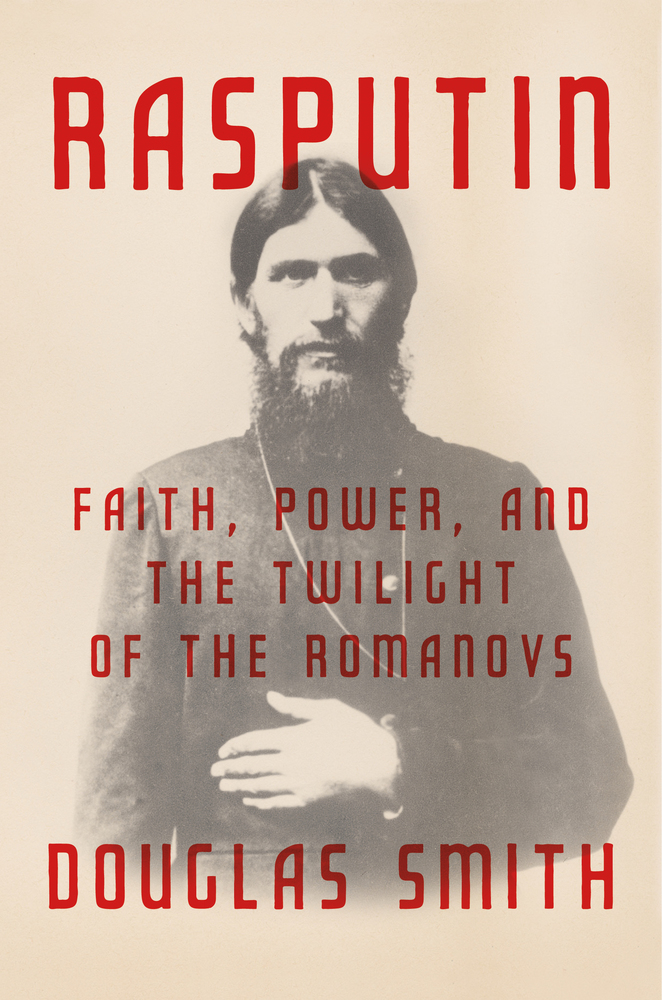

Douglas Smith – Rasputin (Macmillan/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Nov. 2016). Source: macmillan.com Douglas Smith – Rasputin (Macmillan/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Nov. 2016). Source: macmillan.com |

Rasputin remains fixed oxymoronically in the public imagination, Smith observes, as “mad monk” or “holy devil”. His life, one of the most remarkable in modern history, “reads like a dark fairy tale”: an uneducated peasant from deepest Siberia feels called by God to set off on adventures, bewitches the royal family, saves the prince’s life, gets too powerful, and is murdered by the great men of the realm.

“He lived in legend, he died in legend and his memory is cloaked in legend,” wrote the brilliant satirist Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya, known by her penname Teffi, in a fabulously intimate 1924 essay on Rasputin. The piece is one of many gems in a new book of non-fiction, the first ever in English, by Teffi, famous for her sparkling short stories.

The new collection is published in the UK as Rasputin and Other Ironies and in the US as Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me. Anne Marie Jackson has collaborated with Robert Chandler and other translators again to produce a glowing volume of Teffi’s prose, and her version of this essay is both funny and forceful. Teffi describes her encounters with Rasputin and his mythological status: “This man was unique, one of a kind, like a character out of a novel,” she wrote, reveling in Rasputin’s paradoxes: semi-literate peasant and yet counselor to the Tsar? Lustful satyr or saint? “How could anyone not be curious?”

Rasputin’s warning to Teffi: “if they kill Rasputin, it will be the end of Russia. They’ll bury us together” proved chillingly prophetic. Recalling dinner parties with Rasputin, Teffi says she sensed an inner discomfort under his obstinate, hypnotic exterior, that “howling inside him was a black beast.” His political power was undeniable: “He toppled ministers and he shuffled courtiers as if they were a pack of cards.” But after the revolution, she remembered “that black, bent terrible sorcerer”. And, as Smith puts it, his death plunged the whole country into “unspeakable bloodletting and misery.”

Years after meeting him, Teffi gave Rasputin’s autograph to one of his earliest biographers, J.W. Bienstock, whose book was reissued last year in the original French, along with other new biographies, including Frances Welch’s Short Life. Smith’s contrastingly capacious tome measures out a chronological account compiled from archives now scattered across the world. Rasputin includes some extraordinary incidents: tales of friendship and betrayal, scandals, mysteries, miracles, and letters written in blood. He devotes a chapter to Teffi’s account, confirming Rasputin’s love of wine, women and dance.As for his legendary status as “Russia’s greatest love machine”, Smith records that while talk of frenzied orgies and scores of ravaged maidens was fanciful, it is beyond doubt that he had lovers. Even Rasputin’s daughter, Maria, a defender of her father’s legacy conceded that: “Surrounded by women as he was, a man of natural instincts, robust and virile, he may certainly have yielded to many temptations.”

At the same time, paradoxically, Rasputin’s myth had a number of religious guises: as a member of the secret khlystian sect, a pilgrim, prophet or religious elder. It is this heady mix of cult rituals, mesmeric powers and sexual perversion that has fuelled Rasputin’s persistent legend. The same myths have generally deterred serious academics, who – in Smith’s words – saw Rasputin as “too popular, too well-known outside the university to be taken seriously. He had the whiff of the carnival about him, a figure better left to writers of fiction or pop history.” His is perhaps the most recognized name in Russian history, says Smith, citing legions of previous biographies, together with novels, films and songs, like Boney M’s 1978 Euro-disco hit about the “lover of the Russian queen.”

Boney M - Rasputin. Source: Carrie S. / YouTube

The myth continues to spawn bars and nightclubs, ice dances and brands of vodka, while Rasputin remains “practically invisible under all the gossip, slander, and innuendo”. Smith has undertaken an “unusually arduous” search for the truth. In extricating the man from his own mythography, Smith found that Rasputin’s story becoming “the story of Russia itself”. His turbulent biography is a fascinating lens through which to view the “twilight of tsarist Russia” and the violent history of the early 20th century.

Teffi - Rasputin and Other Ironies (trans. Anne Marie Jackson et al. Pushkin Press, May 2016) and simultaneously, in U.S., as Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me (NYRB, May 2016)

Douglas Smith – Rasputin (Macmillan/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Nov. 2016)

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox