After the competition was over, Vadim Buskov, head judge (pictured), spoke to reporters: “Speaking purely in terms of the rules, any team that accepts help from other teams is automatically disqualified. Source: Artem Zagorodnov

February 25, 2013, Sibneft Gas Station, one hour out of Novgorod

I’m in heaven. I was preparing to write about the lack of prepared or hot food—you know, hot sandwiches, fries, warm baguettes, bagels--available at Russian rest stops just as we stopped at a Lukoil gas station that sold hot dogs and burgers! I was so sick of eating cold cuts and fruit in the car, and I was eager for a hot, American-style meal. I ate two hot dogs and fell asleep like a content bear, spread out across the back seat.

Just after two in the morning, we hit the last target we could reasonably reach on this part of the journey. The team got out of the car in subzero temperatures so I could take a picture of them in front of the local post office (proof we were there). We then drove the remaining 150 miles to Novgorod, one of the country's oldest cities, considered a cradle of Russian democracy.

Novgorod had once been the bustling capital of the Novgorod Republic, a large medieval Russian state that stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Ural Mountains and enjoyed strong ties with Europe in the 12th to 15th centuries, that is until Ivan the Terrible’s army seized the city. The region had enjoyed a much more representative and democratic government than other Russian states, in part because of its strong trading ties with Western Europe.

Today, Novgorod remains a very charming and distinct city, a mini-St. Petersburg, that I enjoy visiting. A local military band played a series of farewell hymns as we took off for the remainder of the journey.

Up until this morning, I had been placing larger and larger mental bets on how much I would be willing to pay for a warm shower, shave and hot breakfast.

Because we arrived two hours before the entire group was to reassemble inside the Novgorod Kremlin at 8 a.m. to begin the second major stretch, we stopped at a downtown hotel. I couldn't deny myself this luxury, even if it cost about $80 for effectively 90 minutes. I got my shower in earlier than expected and was feeling very clean and refreshed for the morning meeting.

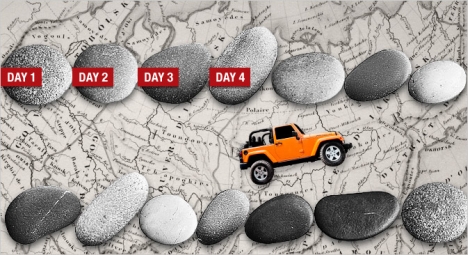

The map of the 2013 Expedition Trophy route. Click to enlarge |

But my team was still stinging a bit from major failures on February 24th. The first mistep was due to the deep snow (if you recall from yesterday’s blog, we kept having to pull ourselves out with ropes). We finally decided to turn around after a local hunter on a snowmobile told us the village we were looking for didn't even exist even though it had been designated a destination by the organizers.

The team missed a second target because it was located in a border region, 18 miles from the Finnish border, and we needed a special permit to enter. We had assumed these two failures were due to confusion on our part or the organizers' own mistakes.

Today, at the February 25th meeting, the organizers announced that both traps had been set intentionally. The explanation, something from a Kafka novel, went like this: “There are 36 targets designated in the instructions we provided you. Most of them will never be attempted by any team; just because they are there doesn't mean the targets are real. So choose your targets wisely.”

This led to an uproar. We weren’t the only team that lost half a day or more pursuing an impossible objective. This may have also influenced the result of the Expedition's second “special track,” which began immediately after the meeting just outside the city.

As in Murmansk, the jeeps lined up side-by-side to complete a 100-meter dash across rough terrain and high snow mounds.

|

| The Expedition teams help the priests overcome a snow mound. Source: Artem Zagorodnov |

This time, however, when the organizers yelled “Start!,” all but one group refused to budge. It was a boycott of this part of the competition: Most teams simply decided the points weren't worth the effort of digging through dozens of feet of snow and the potential damage to their jeeps and equipment. Only the church priests dug away feverishly but unsuccessfully at the first giant snow mound in front of them.

“I wouldn't call it a boycott; we're just tired,” explained Nikolai of the Trust team.

After an hour or so, the other teams got tired of simply standing around in the freezing weather and began helping the priests make it through. An excited announcer yelled into his microphone: “What we've been trying to achieve for the last six years with these expeditions has finally happened! You've finally realized that you're not competing against each other, but against the organizers.

This is what the spirit of Expedition is all about!” However some contestants felt this sudden promotion of Kumbayah camaraderie was a convenient way of covering up waning enthusiasm.

After a few minutes one of the priests grabbed the microphone: “This is what spiritual goodness and being a human being is all about! I'm very proud of all of us. I call on the organizers to distribute the points we'll win among all the teams evenly.”

After the competition was over, Vadim Buskov, head judge, spoke to reporters: “Speaking purely in terms of the rules, any team that accepts help from other teams is automatically disqualified. But there are things more important than rules that can come out during a game like this...” (I found it to be a very Russian approach to sportsmanship). The priests would continue competing.

Source: Expedition Trophy

The time had come for journalists to be assigned to new teams, based on whether reporters wanted to try the long and treacherous route or the short and “pleasant” route.

The most challenging path is through Baikonor Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan—the historic launch site of both the first satellite and the first person in space. The shorter trip is through Russia's Ural Mountains.

I chose the Kazakhstan route of and found myself among a friendly team of employees from the Taganrog-based Lemax Group, a conglomerate involved in gas production equipment, bricks and retail across Southern Russia—more about them in tomorrow’s blog.

They were kind enough to let me grab some McDonald’s before we began the next excruciating leg of the journey. I now realize I am reliving my childhood in as much as every time I see a McDonald’s out a car window, I beg the driver to let me grab something.

View the slideshow. Source: Expedition Trophy

Our mission this time is to make it as close to the cosmodrome as possible within the next 24 hours. At 6 p.m. Moscow time, the organizers will launch five rockets containing weather-balloon equipment and GPS tracking devices. Our goal is to recover at least one of them after they fall to earth – no easy task considering they will most likely fall somewhere in the middle of the vast Kazakh steppe.

Even if we drive nonstop we'll still be around 600 miles from the likely launch location by the time they're sent up. Oh, and we're competing against at least three other teams.

Our only hope is that at least one of the rockets will fly in our direction so we'll be able to pick it up and make the next Siberian location on time. The team has said they have no regrets about choosing the difficult route despite the fact that they'll almost certainly lose the competition if we fail to recover one of the space objects. Off to Kazakhstan!

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox