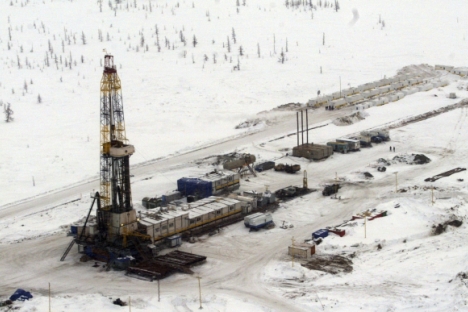

Rosneft oil rig seen at the Rosneft's Vankor oil field in eastern Siberia, about 2,800 km (1,740 miles) east of Moscow. Source: AP

Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin toured South Korea, China and Japan in mid-February 2013, meeting local political figures and the management of leading national corporations.

The only document signing took place in China, where Rosneft signed a memorandum with China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (SINOPEC) on considerably increasing Russian oil supplies to that country. Russian Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich later discussed the memorandum in greater detail at a meeting of the Russian-Chinese intergovernmental commission on energy cooperation.

Russia, China discussing credit schemes for oil, gas supplies - Russian Deputy Prime Minister

Rosneft may supply China with additional 9 million tonnes of oil

Rosneft to attract Chinese, Korean investment to Arctic shelf

According to Dvorkovich's spokesperson, Rosneft could boost its current crude-oil supply to China by up to 9 million tons. Dvorkovich also implied that China might grant Rosneft a loan to implement the new agreement. Rosneft had earlier dismissed a Reuters report that Beijing could lend the company $30 billion in exchange for doubling the existing crude-oil supplies.

At present, Russia supplies China with 15 million tons of crude oil per year, along the East Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline. The ESPO throughput capacity is set to be doubled in the future. In the meantime, Rosneft could resort to a swap scheme, supplying 7 million tons of crude oil a year to Kazakhstan's Pavlodar refinery; in exchange, Kazakhstan's KazMunaiGaz state company would dispatch the same volume of crude oil to China via the Atasu-Alashankoupipeline section.

Russia is keenly interested in boosting oil exports to China, because the current export volumes are not sufficient for the implementation of several joint projects. Back in 2010, Rosneft and PetroChina — a subsidiary of China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) — set up a 49 to 51 joint-venture to build a refinery in Tianjin.

The $3-billion facility with an annual capacity of 10 million tons was originally planned to become operational in 2012. The joint venture expected to make profit not only from crude-oil processing but also through petrol retail via a network of 300 filling stations across China. According to Dvorkovich's spokesperson, the extra crude oil that Rosneft plans to supply to China is meant specifically for the Tianjin project.

As it happened, oil was not the most important topic on the agenda of Sechin's Asian tour. The trip turned out to be largely about advertising shelf projects in the Russian Arctic and promoting international cooperation in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry. These two topics dominated the discussions in each of the three countries on Sechin's itinerary.

In South Korea, the Rosneft CEO showcased the Russian market opportunities to LNG specialist KOGAS and world-leading shipbuilder STX, which specializes in shelf equipment. His audiences in China included CNPC, SINOPEC and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC).

In Japan, Sechin made presentations for the oil and gas producer Inpex, the petroleum exploration company Japex, the Sakhalin Oil & Gas Development Co. (SODECO), and Rosneft's current Sakhalin-1 partners, Itochu and Marubeni.

Between the two, Rosneft and Gazprom hold 80 percent of all licenses for Russia's Arctic shelf. Under Russian law, private companies can only compete for those licenses which have been given up by the two state-controlled majors, which originally obtained them without going through the tender-based bidding process.

Even before the government started awarding shelf licenses to the industry giants, it was understood that Rosneft would gain control of the oil-bearing structures, whereas the gas-bearing ones would go to Gazprom, says Sberbank CIB analyst Valery Nesterov.

However, it quickly transpired that the shelf could not be carved up this way; its structures were poorly explored, and the proven reserves were expected to be made up of natural gas by between 50 percent and 70 percent. As a result, according to Sechin, the Rosneft-controlled structures have been found to hold 21 trillion cubic meters (741 trillion cubic feet) of gas, and those structures already being developed in Kara Sea hold 11 trillion cubic meters of gas.

Shelf hydrocarbons are expensive to extract and will be impossible to sell domestically. The Russian Economics Ministry forecasts that gas prices on the Russian domestic market will not rise to $150 per 1,000 cubic meters until 2015, although the world prices currently stand at $350. In Europe, which currently consumes 70 percent of all Gazprom exports, demand for natural gas is declining steadily.

According to a forecast by the Institute of Communications and Computer Systems of the National Technical Institute of Athens (commissioned by an EC Directorate-General), by the year 2030, annual natural gas consumption in Europe will have dropped to 545 billion cubic meters — down from almost 570 billion in 2010.

{***}

ВР and ExxonMobil, for their part, predict that the natural gas market will boom before 2030. The International Energy Agency says China will be the greatest consumer (634 billion cubic meters a year), and that the country's annual natural gas imports are set to reach 200-300 billion cubic meters. China will account for 56 percent of overall Asian growth in natural gas consumption.

Russia is increasingly turning to Asia for its hydrocarbons exports. According to Sechin, the only way to cash in on the country's Artic gas reserves is to liquefy and export them. Sberbank CIB's Nesterov says the window of opportunity to sell Russian LNG to Asia will be in 2018-2022; if Russia fails to carve a market niche during that period, it will be driven away by Australia, East Africa and the Middle East.

Rosneft touts Gulf of Mexico deal, Arctic exploration

Gazprom, which holds the monopoly on Russian gas exports, has its own interests in the LNG market. The giant's policy is stifling the development of smaller independent producers, who are finding it impossible to acquire financing for their projects.

Gennady Timchenko, co-owner of Russia's second largest gas producer Novatek (which is involved in the Yamal LNG project), told Forbes last autumn that Gazprom Export "has not signed a single contract with consumers yet [for the Yamal gas], nor has it given us any promises" to that effect. Novatek then initiated the drafting of an Energy Ministry bill on liberalizing the LNG market.

Rosneft's Sechin joined the fight against Gazprom's monopoly in early 2013. By mid-February, President Vladimir Putin appeared to back the drive by making the first-ever public mentioning of the possibility of gradually liberalizing the LNG market. According to Dvorkovich, the government could come up with a solution by the end of March. He noted, however, that possible liberalization steps should not result in LNG and traditional natural gas competing head-on on the same markets.

Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak has previously stated that deregulating the LNG market was possible on the level of both individual projects and geographic locations. Nesterov believes the government will introduce amendments to support individual independent projects while formally preserving Gazprom's LNG monopoly. This, however, will require Rosneft to have such LNG projects already on hand.

This is actually what Sechin's Asian mission appears to have been all about: one such possible project could be Rosneft's joint LNG-production facility with ExxonMobil as part of the Sakhalin-1 project. The two companies are aiming their effort at the Japanese market, which has been extremely LNG-thirsty following the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

ExxonMobil is one of the few foreign companies — alongside Eni and Statoil — which participate in the development of the Russian Arctic shelf. The U.S.-headquartered corporation is planning to invest $3.2 billion in the development of Rosneft's oil deposits in the Kara and Black seas.

Rosneft is also in talks with China about LNG exports. According to Dvorkovich, the Russian oil giant expects to reach a basic agreement by late March — in time for the planned visit to Russia by China's new President Xi Jinping. Dvorkovich notes that, although the basic terms and conditions can be defined within weeks, the detailed contractual liabilities will take several months to formulate.

Whatever the case, the very fact that Beijing has signed up to buy 65 billion cubic meters of gas a year from Turkmenistan, against the backdrop of protracted and stalling talks with Gazprom, might prove beneficial to Rosneft.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox