|

| 'Inside the Rainbow,' Redstone Press (September, 2013). Source: amazon.com |

Nonsense and gibberish

A lively performance, featuring music, dance and theater, marked the book’s official launch in the GRAD gallery in London’s Fitzrovia. GRAD’s current exhibition of constructivist models was a perfect backdrop. The script juxtaposed official commentary with excerpts from the poems and stories of Kornei Chukovsky and others.

Chukovsky’s work was, according to a Soviet psychologist in 1926: “an example of the perversion of children’s poetry with nonsense and gibberish.” In Irina Brown’s play, written for the launch party, red-scarfed pioneers reply to the psychologist with: “Once the kittens raised a row:/ Oh, how dull it is to miaow!/ Let us better bark like doggies:/Bow-wow-wow!” Likewise a speech about the “basis of communist morality” is interrupted by a great shout of “ICE-CREAM! МOРОЖЕНОЕ!”

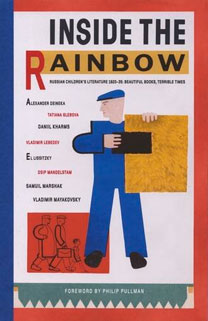

The packed audience included familiar faces from the worlds of art and literature, including children’s author Philip Pullman, who has written an enthusiastic foreword for the new book. Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” trilogy has become a modern classic since the first volume was published in 1995 and is one of the most popular works of contemporary fantasy.

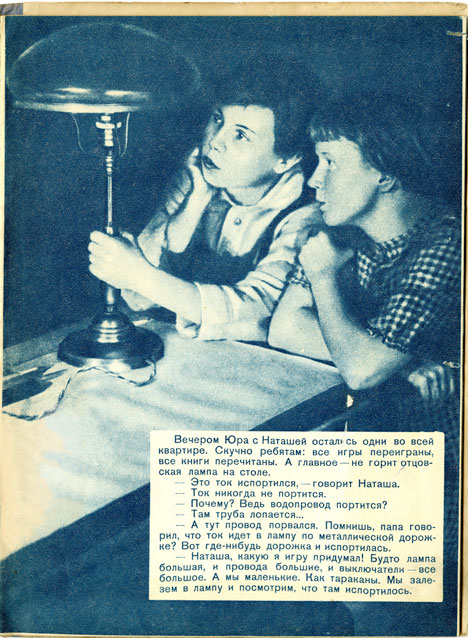

Yura and Natasha alone at home dreaming. Source: Press photo

Ostensibly writing for younger readers, but dealing with complex themes, controversial questions and “the struggle against religious tyranny,” Pullman knows very well that children’s literature can be a powerful platform for big ideas. He ascribes the fact that the “early Soviet period was a miraculously rich time for children's books and their illustration” to growing censorship of writing for adults.

Wit and brilliance

“For a few years Russian children’s books were free of the darkness that descended over the Soviet Union,” Pullman writes, “and the light they shed … sparkling with every conceivable kind of wit and brilliance and fantasy and fun, is here in this book still.” These works are far more, though, than a bright, fantastical refuge from the gathering gloom. Many of them, in terms of style and content, are active parts of an attempt to re-educate children.

“The artistic idiom, both verbal and visual, was … updated,” writes State Hermitage Museum curator, Arkady Ippolitov, in an introductory essay: “In order that children would mesh with the radiant future being built for them, they themselves had to be rebuilt.”

The radical constructivist experiment had not yet given way to the soullessly over-ornate neoclassicism that characterized the later Stalin era. “At first sight it looks like a textbook of suprematism,” said Pullman. He notes how Malevich’s “Black Square” has become Chukovsky’s telephone in Konstantin Rudakov’s classic illustration.

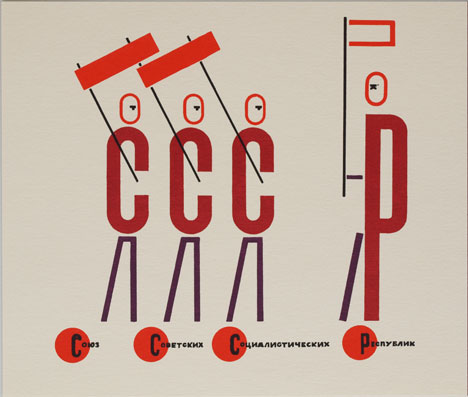

In these pages, you can find El Lissitzky’s cover for Kipling’s “The Elephant’s Child” or Vladimir Tatlin’s cover for a counting book by Daniil Kharms.

USSR poster by El Lissitzky. Source: Press photo

Alexander Deineka brings to the pages of “A Sparkle, An Easy ABC” the same focus and dynamism that characterize his war paintings or his mosaics for the Mayakovskaya underground station in Moscow.

Rhyme and reason

Poetry is notoriously hard to translate and children’s poetry doubly so. Chukovsky’s enduring rhymes and felicitous sound patterns inevitably suffer a little in any English version.

Dorian Rottenburg’s 1970s attempt to render the spirit of the original “Telephone” with simple language and tight rhyme schemes is reproduced in the book. But “I live at the zoo!”/ “What can I do?” “Send me some jam/ For my little Sam” struggles to match the unforgettable rhythms of “Откуда?/ От верблюда./ Что вам надо?/ Шоколада. (otkuda/ ot verblyuda/ chto vam nada?/ schokolada etc)”

For this reason among others, the new book wisely focuses on pictures, with a few poems and stories interspersed. There are also extracts from Lenin’s speeches, or from posters on childrearing; as Pullman observes, “nothing comes without a context.”

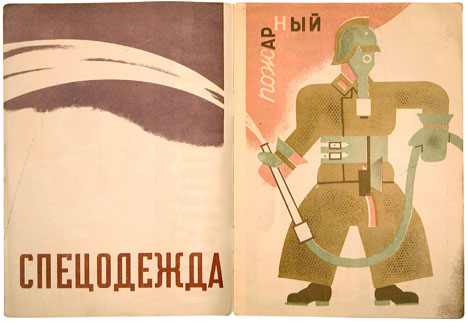

'Special clothing.' Source: Press photo

“Inside the Rainbow” quotes from both the Mandelstams. In an early poem, Osip Mandelstam wrote: “To read only children’s books, treasure/ Only childish thoughts, throw/ Grown-up things away/ And rise from deep sorrows.” There is a “haunting” photo of Osip Mandelstam, after his 1934 arrest; Pullman sees his face as symbolic of “a generation whose creativity was peerless, and by that very fact a threat that had to be crushed.”

Nadezhda Mandelstam later wrote in her autobiography, “Hope Against Hope”: “In the middle of the ‘twenties, when the atmospheric pressure began to weigh more heavily on us, … people at once started to avoid each other… Only the children continued to babble their completely human nonsense...”

The acme of all design

Ippolitov describes Soviet children’s books of this era as “the acme of all design before and after”; but the rejection of modernist experiment, which became official policy in 1932, meant, for many artists and writers, “a publishing ban and, in some cases, physical elimination.”

The books here are all from the incomparable private collection of Sasha Lurye; they contain designs like Lidia Popova’s 1928 illustrations for Mayakovsky’s “Fire Horse,” with its primary-colored blocks of print, or her bold, receding line of matryoshka dolls in a book about toys.

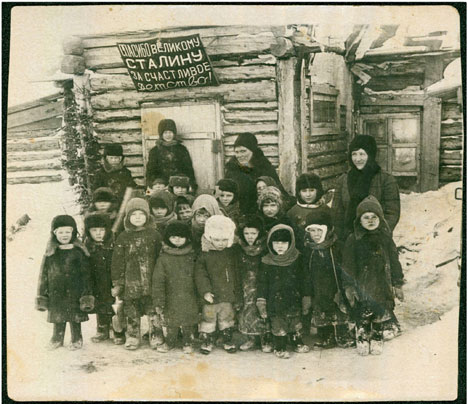

'Thank you, comrade Stalin for our happy childhood,' 1937. Source: Press photo

London-based designer, Julian Rothenstein, founded the Redstone Press in 1986, and has since carved out a distinctive aesthetic niche. Mayakovsky’s early poetry and Osip Mandelstam’s “Journey to Armenia” were among Redstone’s first publications and their stylish 2010 “Russian Diary,” featuring some of the same images reproduced here, became a must-have Russophile accessory.

This book is Redstone’s most ambitious work yet, with more than 300 brilliant pages. Its strength lies in letting these designs coexist with their complex and uncompromising context. There is no sense of trying to ignore the looming horrors of Stalinism; as the subtitle makes clear these pages represent beautiful books and terrible times.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox