Zinaida Gippius was an eminent and significant Russian poet, prose writer and critic. Her poetic and cultural influence went hand in hand with her refusal to conform to prescribed notions of femininity. Admired by writers such as Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein, Gippius was a central figure in the established cultural elite of her day, despite being highly subversive. Yet today, in the West, she is all but forgotten.

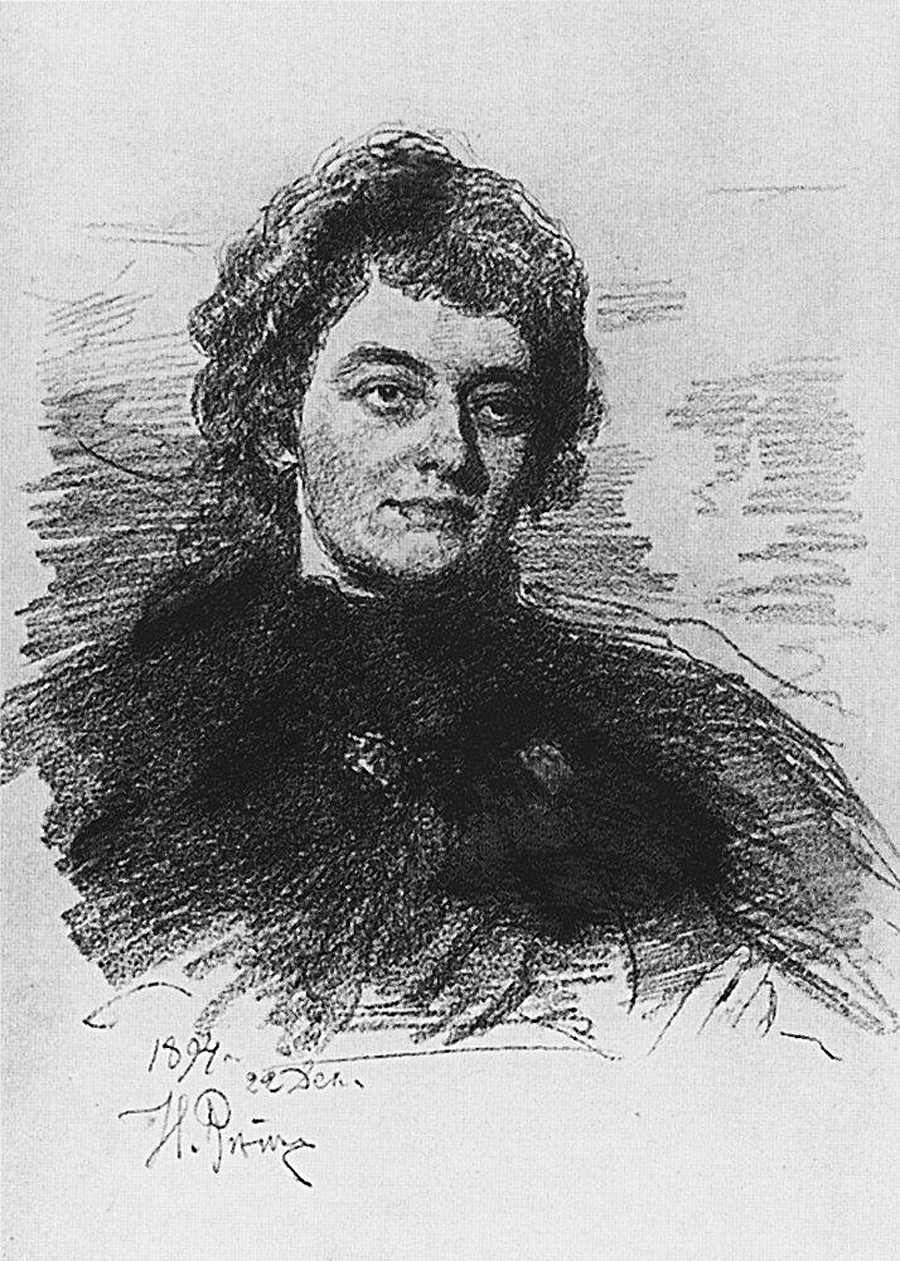

Portrait of Gippius by Ilya Repin, 1894

Isaak Izrailevich Brodsky flat Museum, St. Petersburg.Born in Belyov, Tula (112 miles south of Moscow), on Nov. 20, 1869, Gippius started writing poetry at an early age. She moved to St. Petersburg in 1889 after marrying Dmitry Merezhkovsky, who was a significant poet, writer and literary critic in his own right. The pair soon became key figures in St. Petersburg’s literary elite, hosting illustrious salon gatherings and becoming acquainted with leading figures such as Maxim Gorky, Anton

Following the October Revolution in 1917 and the subsequent civil war, Gippius and Merezhkovsky joined the exodus of many prominent writers,

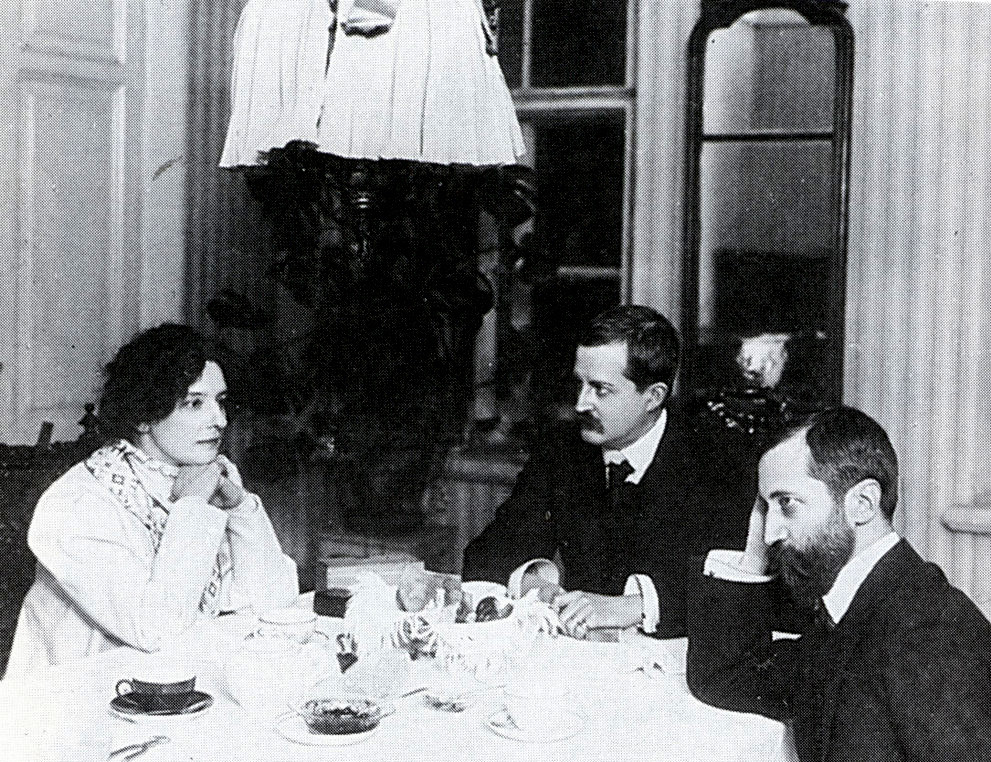

Gippius, Filosofov and Merezhkovsky in 1920

Archive photoGippius was an innovative poet who was firmly at the heart of the first wave of Russian Symbolism, and many subsequent Symbolist poets based their technique on her experiments with rhyme and meter. Symbolist writers saw the written word as a means of apprehending an infinite, transcendental truth, and Gippius played with decadent motifs and themes of the sacred and the profane.

She formulated an ideology that “art should materialize only in the spiritual,” and her spirituality – like many other aspects of her life – was unconventional and linked to a pursuit of spiritual freedom. “My soul is bare, stripped to the purest bareness,” she wrote in her 1905 poem “The Wedding Ring” – “It has escaped, transcended all its bounds.”

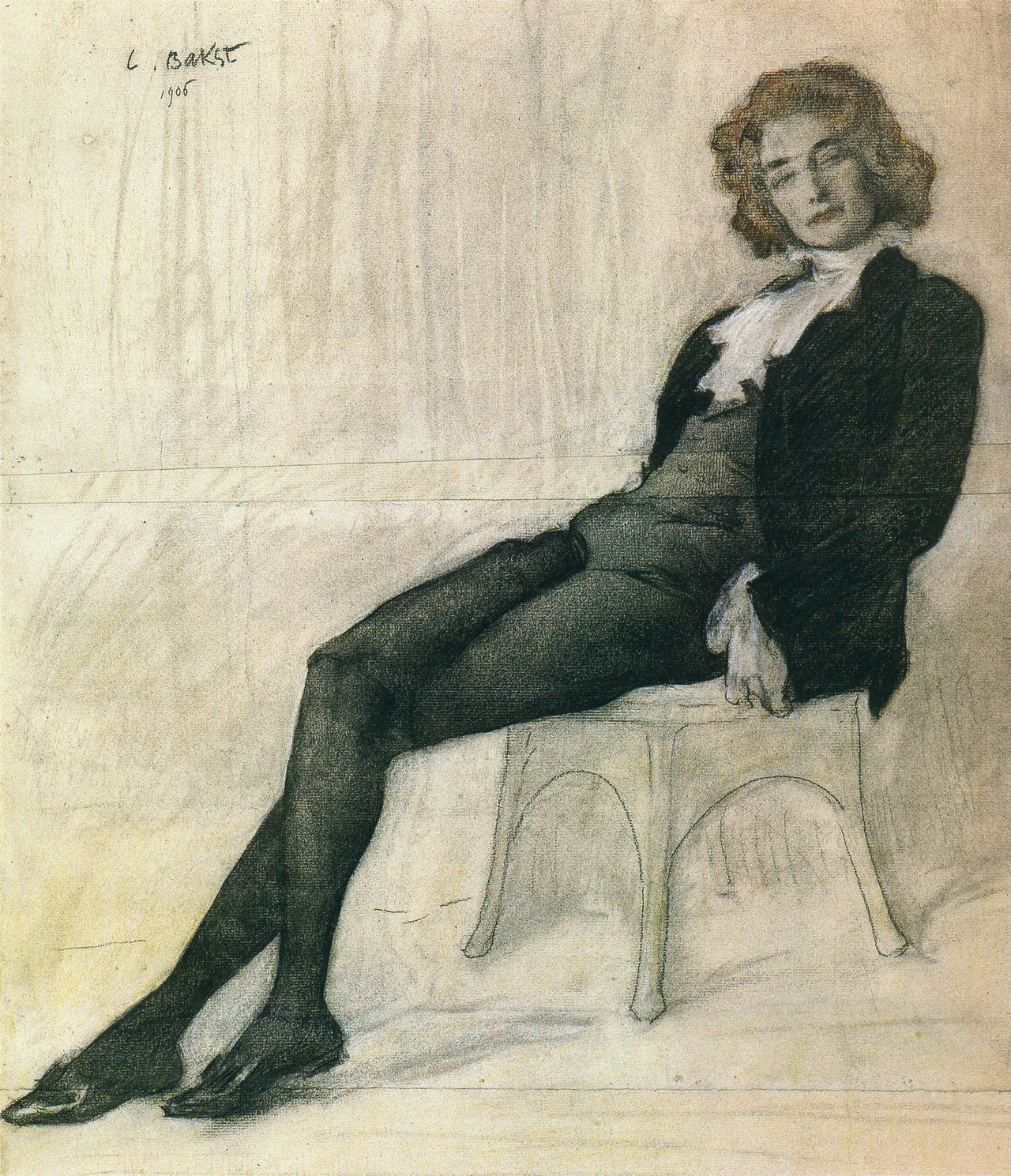

Portrait of Gippius by Leon Bakst, 1906

Tretyakov galleryPoetry was also a space in which Gippius could escape gender expectations. She often adopted a male persona in her

Gippius treated her life as art and used it as another medium through which to explore her creative philosophy. She had a reputation outside of her circle for being a “decadent Madonna” and was likened to the devil. She did nothing to contradict these labels, associating herself with the gothic figure of the spider and using decadent motifs and imagery throughout her poetry:

The silk flares up in flames,

Then turns to a pool of blood;

“Love” is our paltry word

For the

(“The Seamstress,” 1901)

Gippius’s personal style was both elaborate and subversive. She would sometimes wear ostentatiously feminine dress deemed “inappropriate” by many around her, affecting an image and attitude that parodied conventional conceptions of femininity. Andrei Bely, one of the most important Russian symbolists described her as “a human-sized wasp,” going on to say that “a lump of distended red hair … concealed a small, crooked face … the charm of her bony, hipless skeleton recalled a communicant deftly captivating Satan.”

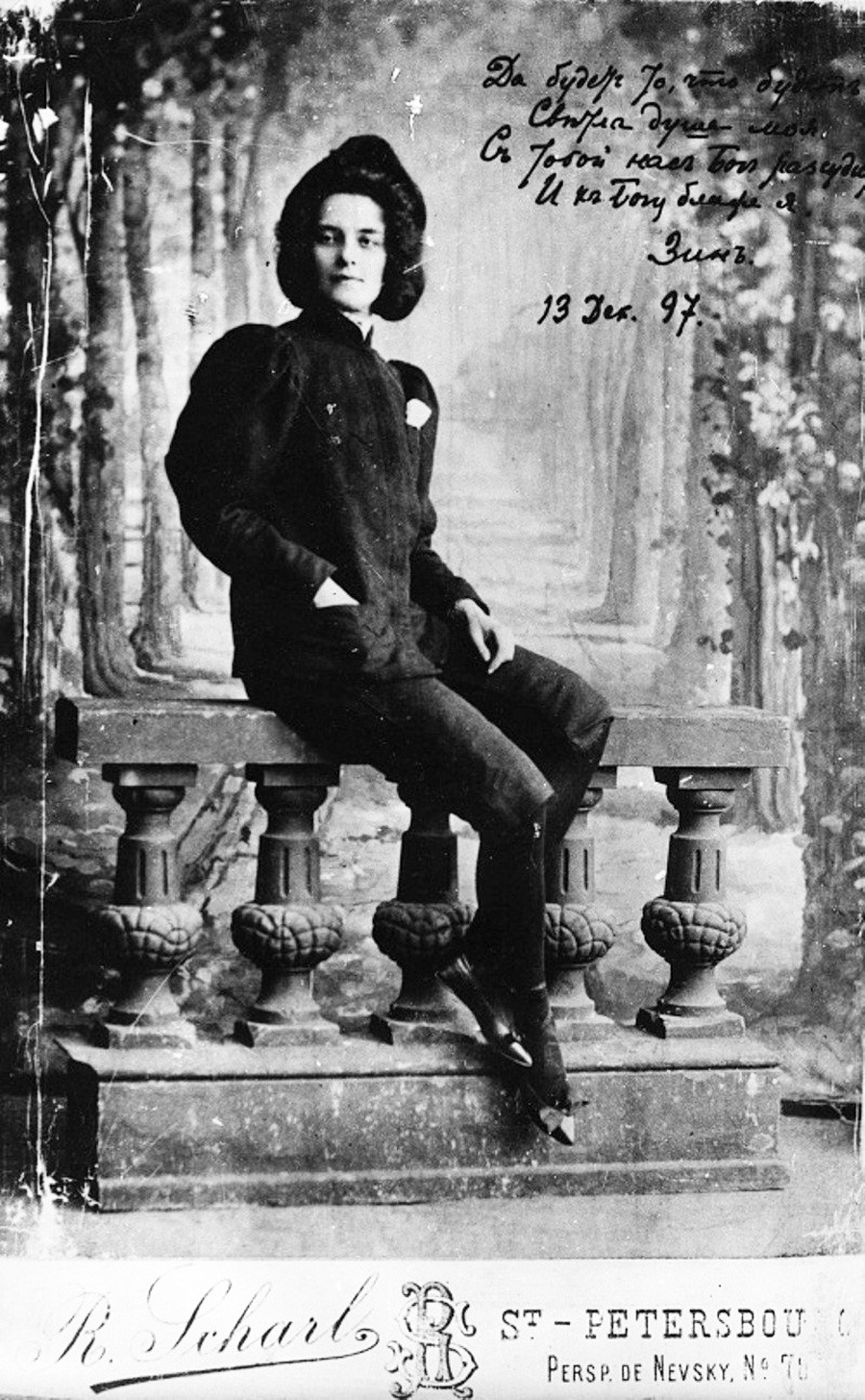

Gippius in the early 1910s

Getty ImagesShe would also frequently dress in male clothes and carry a single-glassed lorgnette, or monocle, much to the horror of her contemporaries. Although unusual, cross-dressing was not unheard of in the early 20thcentury, but Gippius’s presence as a dandy, a stylistically androgynous but essentially male figure, reveals the complexity of her self-crafted identity. The dandy, made most famous in Europe by Oscar Wilde, was typically a decadent and self-conscious individual, interested in artifice and intense artistic sensation, who cultivated an aloof and disdainful demeanor.

Gippius, 13 December 1897

Archive PhotoA fiercely individual woman, Gippius was committed to protecting and cultivating Russian – as distinct from Soviet –

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox