Willem Defoe(L) and Mikhail Baryshnikov performing 'The Old Woman.' Source: Lucie Jansch

“On one occasion a man went off to work and on the way he met another man who, having bought a loaf of Polish bread, was going his way home. And that's just about all there is to it.” So runs Daniil Kharms’ story An Encounter. In its entirety. Not, on the face of it, especially promising material for theatrical adaptation. It has no character psychology, no plot, no time and no setting. It is irreducible; it would take longer to describe than to quote. It is a world of casual violence, falling bodies and food queues, across which move hapless “characters”, all observed by a studiedly indifferent narrator. So why have theatre practitioners, from the British theater company Complicite to American Robert Wilson, wanted to put Kharms on the stage? And how do different audiences respond to his vision?

There is a strong visual element to Kharms' work. One aim of theater is to produce strong images that burn themselves into the audience's memory and suggest meanings beyond their context. Kharms used to play with this himself, often going to the opera in a fake moustache and telling everyone he was his own twin brother. Robert Wilson's production The Old Woman, which toured Europe in 2013 and ran in New York in June 2014, played on this, with Willem Defoe and Mikhail Baryshnikov made to look identical and mirror each other for much of the show.

Defoe said he and Baryshnikov were “extensions of each other,” which was especially effective when the narrator was interacting with other characters. It looked like he was having conversations with himself, suggesting that perhaps all of this was going on inside his head and other characters were a projection of his own neuroses.

Source: Youtube/CalPerformances

A New York Times review compared Defoe and Baryshnikov to Laurel and Hardy, and it is true we are very much in the world of the silent movie, with deadpan naives struggling to act logically in illogical situations. A young theater company, Clout Theatre, recently adapted some of Kharms’ work into a show called How a Man Crumbled, which they toured around various theater festivals across the world. Their production, like Robert Wilson’s, very much seized on the similarity to silent cinema. They performed The Old Woman in silence with piano accompaniment and snatches of dialog projected onto the back wall.

Clout Theatre’s extensive tour gave them interesting insights into how Kharms’ landscape fared in different countries. According to Plaige Sacha, the company’s co-founder, “The German audience was most responsive to the mix of slapstick and philosophy,” while in China, where they had never heard of Kharms, the main preoccupation was with the story’s religious elements. “Do you believe in God?” the narrator asks first a woman and then his friend, who considers it an improper question.

The Chinese audiences, Sacha said, “kept asking about Dostoyevsky,” and indeed some saw The Old Woman as a sort of punishment without a crime. There certainly is a religious dimension to The Old Woman, where the narrator finds a kind of peace at the end in a prayer position, submitting himself to his fate. A lively post-show discussion threw up the questions whether he had been redeemed, is there anyone to redeem him, and does he even need redeeming?

The chief difference between audiences in London and Moscow was what they found funny. The English audiences, mostly unfamiliar with Kharms, were nonetheless ready to laugh from the start. They were there to be entertained. In Moscow, although the audience all knew Kharms’ children’s poems, they were reticent to laugh at first.

|

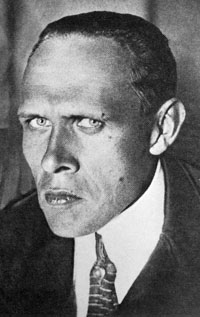

| Daniil Kharms. Source: RIA Novosti |

According to Sacha, this difference became acute in the final scene of the play, which was a version of Kharms’ story Rebellion. It is arguably the most political in Kharms’ oeuvre; a group of “gentlemen” – perhaps military figures – recommend to each other the drinking of vinegar. One gentleman silences everyone with his statement “I shall not be drinking vinegar.” No-one seems to know what to do with this “rebellion”, and the rebel eventually leaves. The other gentlemen reinstate their plan to drink vinegar, shouting “death to the rebels!”

In Clout Theatre’s production this became an extended set-piece with growing tension in the long awkward silences. The gentlemen were visibly pained and shocked by the “rebellion”. In London the audience was bemused by this ending, but in Moscow they were “crying with laughter in the awkward pauses.”

Perhaps this shows an important cultural difference between the two nations, with the British being amused by Kharms’ quieter ironic tone – what the critic Tony Wood called his “yawning nonchalance” – and the Russians responding to the broader satire. Or perhaps, after over an hour in Kharms’ mind, the London audience simply found the relentless breakdown of meaning and convention too tiring and confusing without an understanding of Kharms’ cultural background to guide them.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox