January 19 marks the 150th anniversary of the Russian painter Valentin Serov, who overturned all previous notions of the ceremonial portrait. Serov was born in St. Petersburg into the family of a music critic and composer, but contrary to the laws of continuity chose the life of an artist. // Self-portrait, 1880s

Valentin Serov

Serov’s mother discovered her son’s talent quite early and saw to it that he took lessons from Karl Kopping and the great Russian artist Ilya Repin, whose works include “Barge Haulers on the Volga” and "Reply of the Cossaks to the Sultan." “Paintings this century are stark and forbidding, there’s nothing uplifting in them. I want something uplifting. That’s all I’m going to paint,” said Serov on graduating from the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts. // Portrait of Mika Morozov, 1901

Valentin Serov

1887 saw the appearance of Serov’s most famous painting, “Girl with Peaches,” (1887) which shows Vera, the daughter of renowned philanthropist and collector Savva Mamontov. No other Russian artist ever conveyed the poetry of youth with such captivating freshness or masterful technique. // Girl with peaches, 1887

Valentin Serov

His next picture, “Girl in Sunlight,” is also a celebration of youth, freshness and tranquil joy — a distinctive step towards post-impressionism in which the focus is on the unison of man and nature. “All I’ve ever sought is the freshness that you feel in nature but don’t see in pictures.” // Portrait of Maria Simonovich, 1888

Valentin Serov

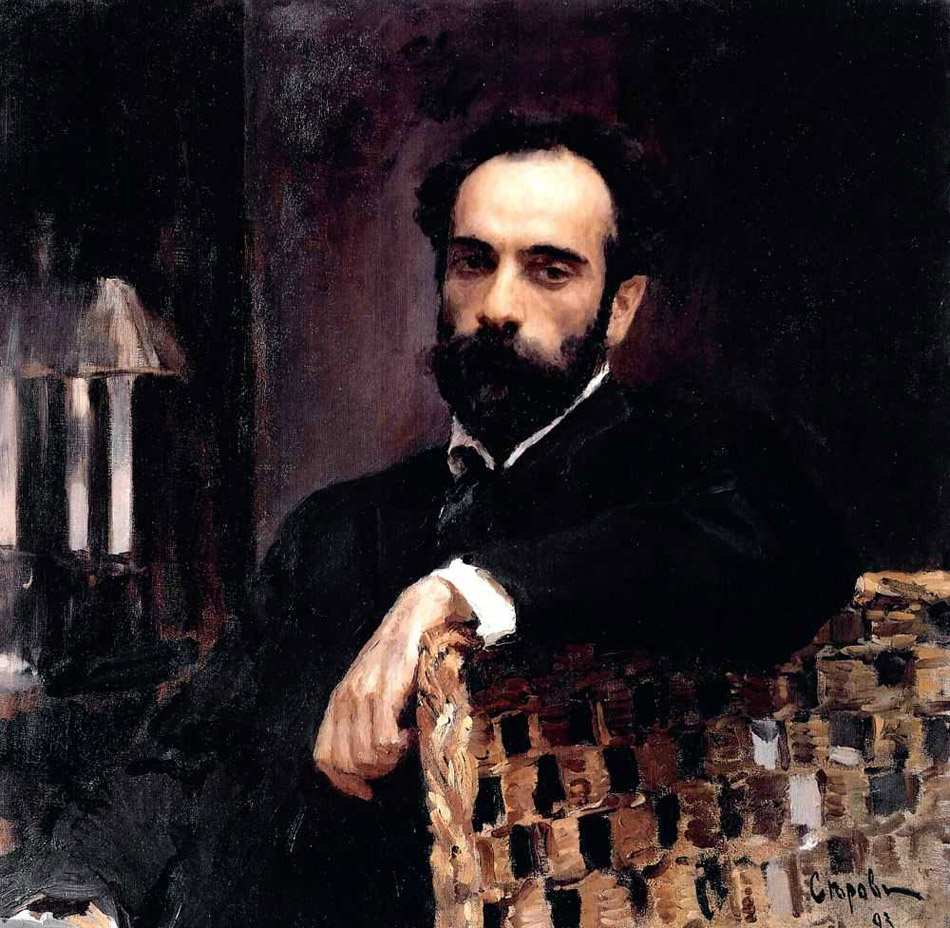

Constantly perfecting his craft, in subsequent years the artist created a gallery of the most famous people of the age, including monarchs and princes, industrialists and bankers, actors and artists. // Portrait of painter Isaac Levitan, 1893

Valentin Serov

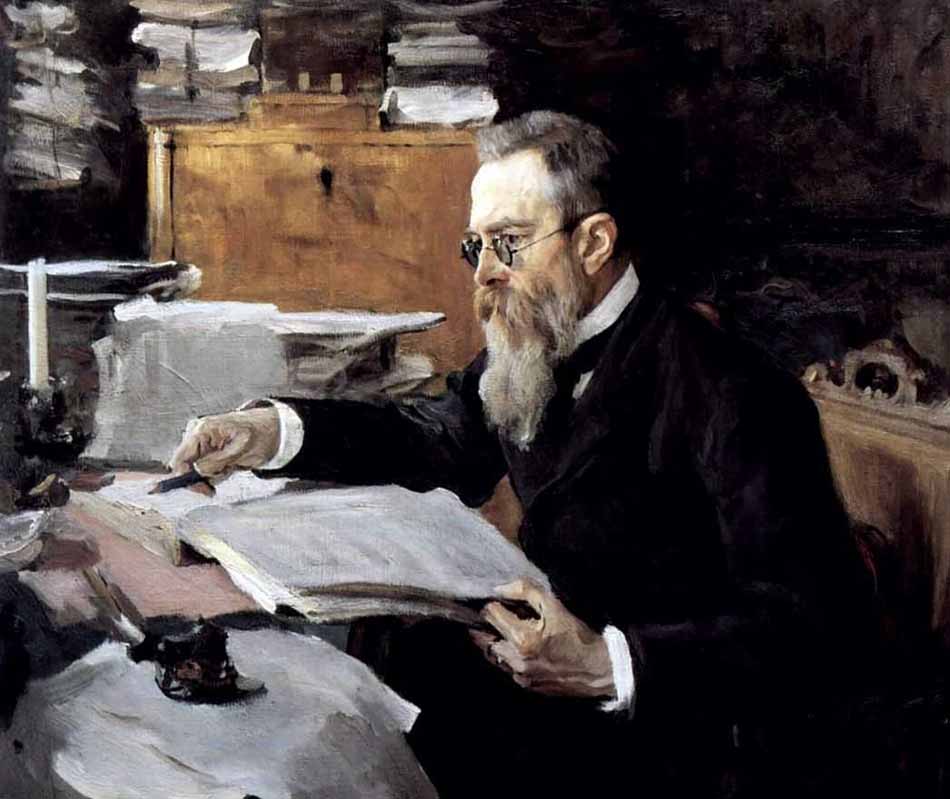

Many ceremonial portraits at the time were painted according to a template. Having found a formula that worked, artists used it repeatedly, depicting their subjects in the same poses time and again. // Portrait of composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, 1898

Valentin Serov

Serov’s formal portraits of the late 19th century did not feature banal poses or static heroic postures: on canvas his models did not turn into ceremonial depictions, but remained themselves. His portrait of Nicholas Romanov is one of the finest portraits of the last Russian emperor. // Portrait of Nicholas II, 1900

Valentin Serov

In the 1900s Serov’s portraits were of celebrated figures marked with the stamp of exclusivity and proud solitude, as if ascended on a pedestal. The disquieting atmosphere of revolution brought such images to life. “This is nothing short of a monument to Yermolova!” wrote the architect Fyodor Shekhtel, so expressive was Serov’s portrait of the Russian actress that it resembled a sculpture. // Portrait of Maria Ermolova, 1905

Valentin Serov

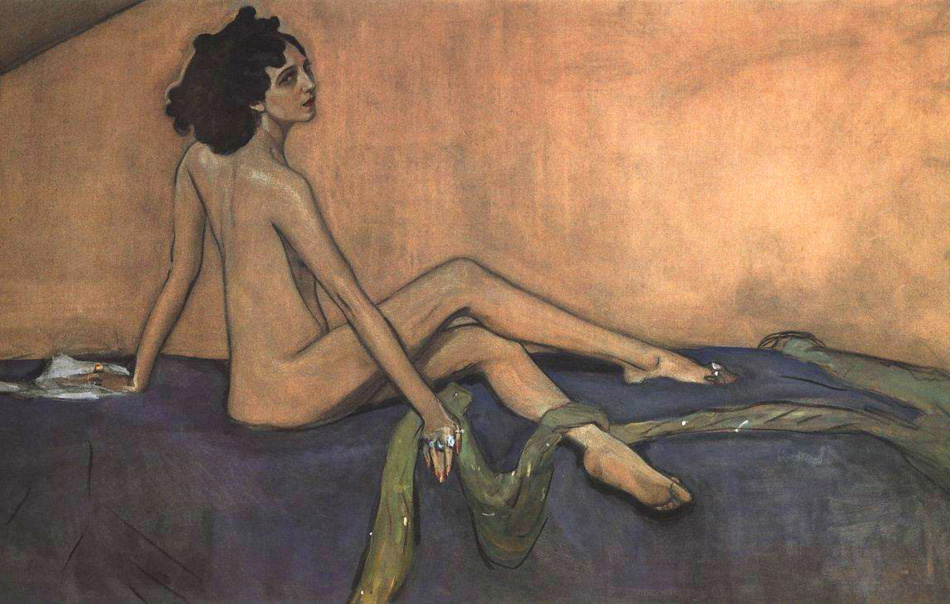

Two of the highlights of Diaghilev’s seasons, the ballets Cleopatra and Scheherazade, were a sensation. The main roles were performed by Ida Rubinstein, in whom Serov saw “Egypt and Assyria miraculously resurrected in this extraordinary woman ... There is monumentality in her every movement — nothing less than an archaic bas-relief brought to life.” // Portrait of Ida Rubinstein, 1910

Valentin Serov

Last autumn “Portrait of Maria Tsetlin” went under the hammer at Christie’s for £9.26 million, becoming at once the most valuable work produced by the artist and the most expensive piece sold during the so-called “Russian auction.” // Portrait of Maria Tsetlin, 1910

Valentin SerovAll rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox