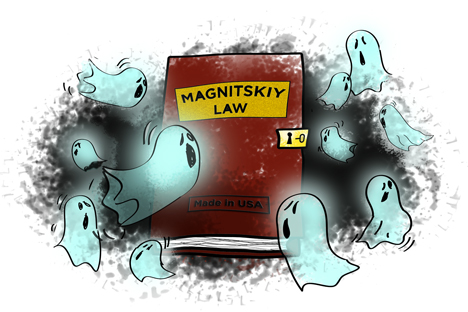

Drawing by Niyaz Karim. Click to enlarge the image.

The news about the posthumous trial of Sergei Magnitsky, a tax auditor who died in a Moscow pre-trial detention facility in 2009, has sent a tsunami wave of excitement, almost exhilaration, through the Western media community.

“A medieval show trial,” “an absurd,” “a travesty”—are just a few of the most popular definitions used by Western journalists to describe the Magnitsky tax evasion case being heard at the Tverskoy District Court in Moscow. Allusions to the literary masterpieces by Nicolai Gogol, Franz Kafka and Mikhail Bulgakov were abundantly invoked.

Completely lost in this cacophony of condemnations was the fact that the late Magnitsky had a co-defender who is perfectly alive and apparently quite well: William Browder.

Browder, in addition to being Magnitsky’s former boss, is the driving force behind the notorious Magnitsky Act adopted by U.S. Congress at the end of last year. In the case, Russian law enforcement officials allege that Hermitage Capital, an investment fund owned by Browder, used illegal schemes designed by Magnitsky to evade $16.8 million in taxes.

Curiously, one of the tax evasion tools seemed to involve the creation of sham investment subsidiaries of the Hermitage Capital, making the reference to Gogol’s “dead souls” particularly relevant.

In the years following Magnitsky’s death, Browder has been insisting that his primary goal was to reveal “the truth” about what happened to his former subordinate. Yet, when the opportunity to tell his side of the story presented, Browder turned out to be much less forthcoming.

Last year, a former Moscow police officer, one Pavel Karpov, whom Browder had repeatedly implicated in Magnitsky’s death, launched libel and defamation proceeding against him in the High Court in London. Instead of using the podium of the High Court to tell “the truth,” Browder instructed his legal team to fight for case dismissal.

There is absolutely no indication that Browder would be available to testify in the Moscow trial, either. True, he’s been barred from entering Russia since 2005; however, he has enough financial resources to send a team of lawyers to Moscow to clear his name and the name of Magnitsky, whom Browder would often call a friend.

But so far, all signs are that Browder would rather play the part of another “dead soul.” Apparently, he prefers “telling the truth” exclusively to a friendly audience of professional Russophobes at the both sides of the Atlantic, without being forced to answer tough questions.

One can understand that putting Magnitsky on trial, however bizarre trying a dead man would appear to be, serves an important purpose for Russia: to prove that the man after whom the anti-Russian Magnitsky Act was named was in fact someone who had committed serious financial crimes.

The only problem with this logic is that the trial comes too late. Instead of carelessly watching Browder’s relentless lobbying of the Act in U.S. Congress, Russia should have become equally relentless in publicizing evidence of Magnitsky’s—and Browder’s—illegal acts.

Now, unfortunately, the Magnitsky trial looks more like a desperate attempt at revenge, a sequel of sorts to the scandalous Dima Yakovlev law hastily adopted by the Russian parliament in response to the Magnitsly Act.

And yet, there is still a lot at stake for Russia in this “dead souls” game. Attempts are underway in Europe to enact anti-Russian laws modeled after the Magnitsky Act. Regardless of the outcome of these efforts, Russia must finally learn how to use soft power instruments to protect its vital interests in Europe, the United States and elsewhere in the world. Otherwise, unfriendly - or even openly hostile - legislations will keep popping up one after another.

In the meantime, the trial has been postponed until March 22 to give the state-appointed defense attorney more time to prepare for the process. We all thus have enough time to re-read Gogol’s immortal creation.

Eugene Ivanov is a Massachusetts-based political commentator who blogs at The Ivanov Report.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox