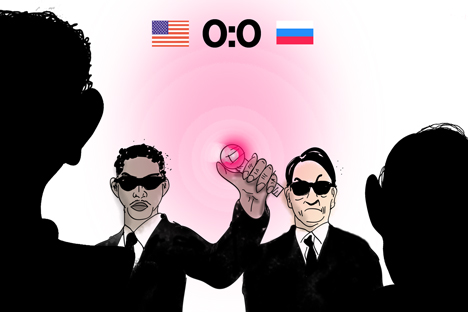

Drawing by Niyaz Karim. Click to enlarge.

Before U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s first visit to Russia, which took place just three months after his appointment, the trip was accompanied by such adjectives as “long-awaited” (or even “belated”), “important,” and “crucial.”

These labels indicate that the visit was accompanied by high expectations that Kerry’s meetings might help to ease the tensions between the U.S. and Russia that have increased in recent months.

The reset of bilateral relations suggested by Vice President Joe Biden and pressed jointly by Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton a few years ago has gradually exhausted itself, leading politicians and experts to talk about a need for a new reset, although a new reset would likely repeat the fate of the first one.

The whole idea behind the reset was to leave behind the contradictions that affected bilateral relations in the past. These include the 2008 conflict in South Ossetia, NATO-led intervention in Libya, President Vladimir Putin’s refusal to visit the U.S. in 2012 for the G8 summit, followed by the Magnitsky list and the Russian response.

This long series of events has brought Russian-U.S. relations down to one of their lowest points in recent history. In February, Biden suggested making a new effort at increasing cooperation and now this message has been delivered to Vladimir Putin by Secretary Kerry.

While such an initiative would be welcomed, any expectations surrounding one should be scaled down, and the focus of a new start or re-reset should be on the long-term.

First of all, if a new reset if takes place, it won’t last long. Recent history indicates that an international crisis in which the U.S. and Russia are on different sides takes place every three to five years.

In 1999, after a start of the war in Kosovo, Russia cut its relations with NATO. In 2003, the two countries took a different approach towards Iraq.

In 2008, Russia fought against a Georgian military that had been armed, trained and funded by the U.S. Washington and Moscow have found themselves on different sides of so many different arguments in the past that it is unrealistic to expect this not to happen in the future.

Domestic and global issues forcing Russia and the U.S. apart can and will arise. It is only a matter of time.

Second, expectations for the relationship are never exactly the same on both sides, especially after a successful high-level meeting. With a very centralized decision-making system, Russia’s international affairs policy center is in the Kremlin.

The U.S. foreign policy mechanism, on the other hand, is more balanced since there are various bodies participating in it, many of which are not subordinate to the executive branch. Differences in political systems result in a policymaking misbalance.

For example, the U.S. president cannot stop a Congressionally approved decennial defense program based just on a successful meeting with his Russian counterpart. Moscow leadership, on the contrary, fails to understand why there is sometimes a decade-long pause between a negotiation and policy-level progress in the U.S.

As a result, there is a mutual lack of trust: Moscow sees promises without fulfillment, while the U.S. lacks reliability and transparency in Russia’s foreign policy.

Third, a reset will have its enemies. The two countries share a long history of controversial relations, and any attempt to change that faces internal opposition. Either within the electoral framework or during a midterm reshuffling, domestic political players will ask those trying to restart the relationship what previous efforts have achieved.

Russia and the US to call conference on Syria

Russia, U.S. agree to encourage Syrian government, opposition to negotiate - Lavrov

Putin expects to meet personally with Obama in the near future

Photo of the day: US Secretary of State John Kerry walks at the Red Square in Moscow

President Obama had to defend his relations with Russia against Republicans; former President Dmitry Medvedev had to defend his cooperative approach towards the U.S. from a broad range of critics including members of the ruling United Russia party and Putin’s inner circle. There is no reason to think this will not happen again in the future.

So what can a fresh start achieve? Kerry’s visit will allow the two sides to continue high-level talks on nonproliferation, cyber security, terrorism, Syria and missile defense, among other issues. This all constitutes a very narrow security-related scope that will achieve a certain amount of progress until tensions increase again.

The one way to get bilateral relations out of this reset-crisis pendulum paradigm is to expand the scope of the relationship beyond the security arena. With very limited U.S.-Russia trade and investment contacts, one area where seeds of progress could be planted is with people-to-people exchanges in education and science.

In the 1960s, France and Germany launched an exchange program for young people to repair relations after World War II. Some 8 million people have taken part in that program.

When Japan decided to open itself to the world on a new scale in the late 1970s, it started a large-scale exchange program that has brought thousands of recent graduates from around the world to teach foreign languages in Japanese schools.

Following a proposal by Barack Obama, China and the U.S. recently launched a joint initiative to encourage Americans to study in China.

In Russia-U.S. relations, that part is largely missing, especially after the U.S. cut funding for the prestigious Muskie graduate level fellowship program for talented young Russians. Yes, international educational and scientific exchanges take lots of time to bring results, but their benefits can hardly be overestimated.

According to Oxford University research, $1 spent on investment promotion brings $189 in foreign direct investment. That can by multiplied by at least two or three times for joint projects in education and science.

The Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, established jointly by Russia’s Skolkovo Innovation Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, may be one of the few remaining long-term projects that can bring the two nations together by bridging the gap between their future scientific and entrepreneurial elites.

More effort is needed to bring the countries closer.

Presidents Putin and Obama will finally meet in June after a year-long pause and then they are to meet again in St. Petersburg at the G20 summit in September. Most likely, they will resolve some of the standing issues, declare progress on some of the remaining and announce a better stage in the bilateral relations.

However, if they went beyond that and launched a new people-to-people public diplomacy track, they could bring the relationship to an entirely new level.

Alexey Dolinskiy is a partner at Capstone Connections consultancy. He graduated with a Master's degree in Law and Diplomacy from the Fletcher School and got his PhD in political science.Currently he works in corporate diplomacy in the Asia Pacific region and in Europe.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox