The manufacturer's museum. Source: The Motovilikha plant

Quality artillery pieces were a core element of the Russian Imperial Army, helped defeat the Nazi forces in 1945 and still provide the bulk of the heavy conventional firepower of Russia’s armed forces. Yet, relatively few people even know the name Motovilikha.

Since the rein of Tsar Peter I (Peter the Great) in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Urals region has been the nucleus of Russia’s military steel-making industry, mining ore and transforming the smelted metal into a full range of firearms and weapons for the army. The foothills of the Ural Mountains were rich with all necessary resources ranging from huge reserves of timber for fuel to a large labor force from nearby villages and a network of rivers for transport.

The southern Urals region was actively developed during Peter’s reign before his successors turned their attention to more central and northern areas. With Russia fighting on numerous fronts in the early 18th century and in need of increasing quantities of weaponry, the still untapped central Urals region provided a platform for creating a new industrial unit.

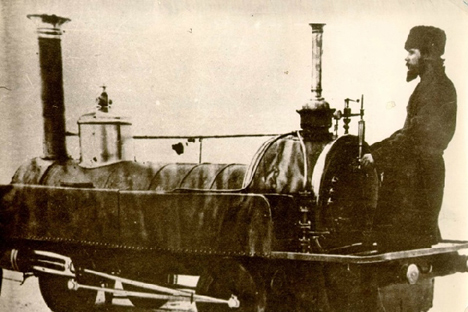

The first locomotive, 1872. Source: The Motovilikha plant

In 1736, Empress Anna Ivanovna ordered Vasily Tatishchev, the head of metallurgy in the Urals, to found a smelter in the Prikamye forests near the Kama River. Initially he was only tasked with producing steel for the existing facilities there. As was standard at the time, his enterprise performed the full production cycle, from ore extraction to the final steel processing and production of ingots.

For half a century the main function of Tatishchev’s plant was to supply crude steel blocks for the manufacture of rifles and large guns. But by the late 18th century the demand for weapons had grown so much that the decision was made to establish a new factory for the additional production of guns near the village of Motovilikha where the workers from the metallurgical workshops lived.

The new Motovilikha guns finally demonstrated their effectiveness in all wars Russia waged in the first half of the 19th century. These included battles against Napoleonic France, the Ottoman Empire, the Poles and Hungarians, while also defending Sevastopol during the Crimean War.

However, the ongoing quest to develop arms production demanded the modernization of the existing facilities, since the innovations of the industrial age could not be implemented using old technology. In the second half of the 19th century, Russia launched a massive refurbishment program for its weapons factories, including at Motovilikha. The scattered metal smelting and gun-casting workshops were united into a single production line and from 1871 work began to combine all weapons factories in and around the city of Perm.

The view from above. Source: The Motovilikha plant

By 1914 every third cannon manufactured in Russia came from here. But even before this it had several major accomplishments under its belt. In 1868, Perm’s gunsmiths created a 60-centimeter cannon that weighed some 45 tons and fired shells weighing 500 kilograms. Referred to as the Tsar’s Cannon, it was intended for Kronstadt, the sea fortress guarding the gulf leading into Russia’s capital, St. Petersburg.

The enterprise also launched the first steamship in the Urals in 1871, the first steam locomotive in 1872 and the first power plant in 1886. The local specialists pioneered new developments in metallurgy and in 1875 they built the world’s largest steam hammer, which weighed a staggering 50 tons and was used in the first open-hearth furnace in the Urals the following year. In 1893, Nikolai Slavyanov, a metallurgist from Perm proposed a new method of welding using consumable electrode, which today is still the main type used in steel production worldwide.

The factory's staff. Source: The Motovilikha plant

World War I boosted production greatly with every fifth gun supplied to the front carrying the stamp of its workshops. After the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the subsequent Civil War, the Soviet authorities invested heavily in the development of heavy industry here and the industrialization of the 1930s led to a complete revival of its production facilities.

In addition to guns, these facilities began to produce a wide range of metal products, from machine tools to machinery, cranes and construction equipment. It was here that the first Soviet steam-powered excavator was built.

However, World War II again required Motovilikha to return to its primary speciality – the manufacture of big guns. In 1941-1945, every fourth heavy weapon fielded by the Red Army was made here, with the plants achieving an eight-fold increase in artillery production.

After the war, production for civilian use began again and the farm equipment, turbines, and mining equipment produced here were widely used in the USSR and abroad. In 1958, the United States and West Germany also bought licenses to manufacture the Perm-built turbine-driven boring unit.

Inside the Motovilikha plant. Source: Igor Kataev / TASS

Niche civilian products were also developed in the difficult transition period of the 1990s, but the advent of the 2000s demanded a rethinking of the enterprise’s function. In 2011, a new ultra-modern artillery production line was launched at the Motovilikha workshops and it is now the country's only full-cycle artillery production line. According to its development plans, total annual sales of the new facilities should reach $1 billion by 2017, as this nearly 300-year old enterprise completes its transition to a company firmly rooted in the future.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox