Modern lapta. Source: Press Photo

A couple of years ago, a friend of mine went to the U.S., where he teamed up with some other Russians to rent a house jointly. Despite coming from different regions of Russia, they decided to play a game known to every one of them – knives, which involves sticking a knife in the earth to “cut” a part of the opponent’s territory. A call by the neighbors resulted in the police arriving at the premises, but once the officers discovered the peaceful nature of this game, they also quickly learned to play it. Knives has its roots in the obsolete game of svayka, popular in pre-revolutionary Russia.

Svayka

It is no coincidence that the game of svaykawas used as a metaphor for sexual intercourse in one of the ancient Russian epics.

Svayka. Source: Press Photo

The symbol of one of the world’s oldest religious cults, Sivaism, is a lingam, a combination of a ring (a female symbol) and a rod (a male symbol) – the same objects used in svayka, which has deep roots in Russia’s pre-Christian period.

The rules of svayka

The rules of this traditional game were simple. A thick iron ring two inches in diameter was placed on the ground, and the aim of the game was to repeatedly “shoot” the ring with a pointed iron rod, called a svayka, so that the rod would go through the ring and stick into the ground. The weight of the svayka, thrown by hand, depended on the age of the players – from 1.7 lbs for children to 4.4 lbs for adults.

The game was hugely popular among Russians of all walks of life, peasants and nobility alike. Even young princes, brought up in the confinement of royal residences, knew its simple rules. The game was also linked to a major turning point in Russian history.

The last son of Ivan the Terrible, Prince Dmitry, was weak and suffered from epilepsy. When his elder brother Fyodor took the throne, Dmitry was sent to the town of Uglich to protect him from the stresses of court life in the capital. In 1591, when Dmitry was only nine, reports of his death reached Moscow – it was said that Dmitry had mortally wounded himself with a svayka rod when he went into a seizure during a game.

Rumors spread that Dmitry had been killed by boyars who didn’t want him to rule the country – Russians didn’t believe that the prince could continue to grip a rod during a seizure. Whatever the truth, Dmitry’s death marked the beginning of a dynastic crisis for Russia. Known as the Time of Troubles, this period of instability ended with another dynasty, the Romanovs, gaining power. But what about svayka? After the Revolution of 1917 and abdication of the last tsar, it gradually developed into the game of knives.

Lapta

Svayka was mostly a leisure game, but to play lapta,one had to be physically fit. Lapta, a bat-and-ball game very similar to cricket and baseball, requires two teams – one serves the ball with a flat wooden bat, while the other tries to catch it and tag members of the serving team. One important asset of lapta is its cheapness – all you need is a wooden bat and a ball. As well-known writer Alexander Kuprin wrote about lapta, “it requires wit, deep breathing, team spirit, attention, resourcefulness, speed, accuracy, firmness of shot and deep confidence that you won’t be defeated. This game is not for loafers or cowards.”

The origin of lapta is obscure, and there are no signs of it being played in Russia before Peter the Great, who introduced lapta to the Russian army in the early 18th century. Could Peter, who visited England during his trips to Europe, have borrowed the idea of lapta from cricket? We’ll never know, but Peter’s initiative had long consequences: The game was used as a means of physical exercise in the military until the 20th century, when it became popular nationwide.

Official competitions were held only for a short time in the 1950s, but lapta grew into one of the favorite games for children in Russian provinces, where it was played in villages and suburbs. For example, in 1980s in the Russian city of Tambov, lapta was very popular among kids on the outskirts, but children in the city center didn’t even know about it.

In the 1990s, a Russian lapta federation was created and now lapta championships are held in most of Russia’s regions. Yet another traditional game that has recently been rejuvenated is gorodki.

Gorodki

Of all Russian games, gorodki is the most authentic, having few analogues in other cultures. The aim of the game is to knock out groups of wooden pins arranged in various patterns by throwing a bat at them.

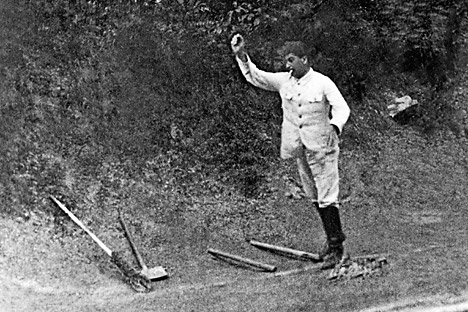

Stalin plays in gorodki. Source: RIA Novosti

The game is most likely to have been invented in Russia in the 18th century. German artist Christian Geissler wrote of gorodki in 1805: “This game is known only in Russia, because it requires considerable strength. It is played by the strong and sturdy people that live in this harsh country… When a big company of Russians gathers, they usually play this game.” The foreigners also noted that upon the end of the game, the members of the winning team usually rode the backs of the losers – a habit that disappeared towards the end of the 19th century.

Gorodki in the 20th century

From the 1930s onwards, gorodki championships were held annually in the USSR; by the 1970s, over 300,000 people in the country played the game. By the end of the Soviet era, the game’s popularity had faded, but it gained a new lease of life in the 90s. Lately, Russian leaders have also demonstrated their love for the game: in 2006, Vladimir Putin was spotted trying his hand at the bat in Izhevsk, and in 2012, Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin showed his skill, knocking down one of the most difficult patterns in one throw.

Gorodki was hugely popular among common folk in towns and villages, and shunned by the nobility, except during military service – count Leo Tolstoy recalls himself and his noble comrades playing gorodki in their army camp in the Caucasus. But when the Soviets came to power and the nobility was swept aside, gorodki stood out as an authentic game played by peasants and proletarians. Many Bolshevik leaders demonstrated their love for gorodki. In his last years, Vladimir Lenin used to play it for a couple of hours every evening; but Joseph Stalin loved the game even more.

“Billiards, skittles, gorodki – anything that required a sharp eye was a sport for Father,” – Svetlana Alliluyeva, Stalin’s daughter, wrote. His country house was equipped with a gorodki court, and he often practiced with his guards. As Eugene Katzman, an artist who visited Stalin at his dacha, recalls: “Joseph Stalin was the best at gorodki . When he aimed with a bat, his face became particularly energetic and expressive, as if he was fighting for his opinion at a party congress”. Stalin often played gorodki with his guests, and was fond of boasting of his mastery of the game.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox