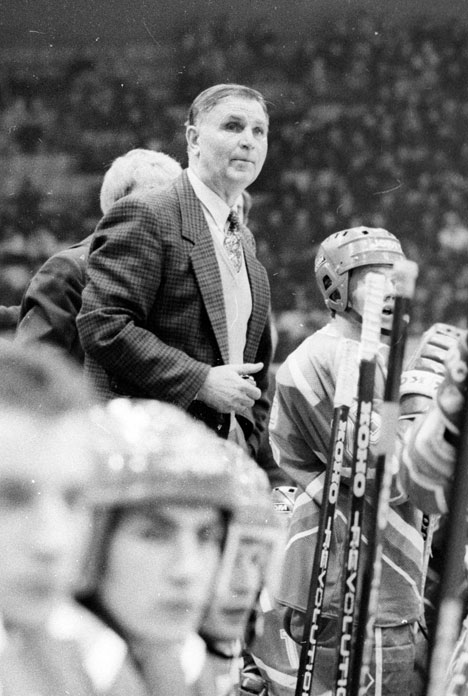

Viktor Tikhonov and the Team USSR, 1991. Source: ITAR-TASS

For many Russians, the death on Nov. 24 of hockey coach Viktor Tikhonov spelled the end of an era.

North American hockey fans respected him as an adversary, whether his Soviet team was overcome, as by the U.S. in the Miracle on Ice at the 1980 Olympics, or unstoppable, as in the three Olympics after that.

Tikhonov, who died aged 84 after a long illness, was never a household name in North America though. In Russia he was a national hero, but more than that, a symbol of an entire age.

Calm and authoritative, with alert eyes, he was a reassuring presence for many, the embodiment of a long-ago time when Soviet sporting dominance was unquestioned and deservedly so. Until the end, he was keen to restore that dominance, as his former goalie Vladislav Tretiak, now head of the Russian Hockey Federation, remembered.

"He devoted his entire life to hockey,” he told the R-Sport news agency. “Even when I was with him in hospital, we were discussing what needed to be done … to raise the Russian national team to the very highest level.”

In Tikhonov’s 1980s heyday, any loss by his Soviet team was a shock. Even during the pain and chaos of perestroika, victory at the 1988 Olympics showed there was still a place – the ice – where the Soviet Union was thriving. At his final Olympics in 1992, he led the Unified Team, which brought together most of the newly-independent ex-Soviet nations for one last shot at gold. It was rare moment of unity at a time when Soviet Union, so recently a superpower, had fractured into 15 countries.

By then, however, it was not just Tikhonov’s team that was an anachronism. His coaching style had been inherently bound up with the Soviet system and, though he tried to continue as coach of Russia and his old club CSKA Moscow, it was never the same.

Tikhonov’s career embodied a very Soviet way of looking at sports. Athletes were servants of the state, working for achievements that would boost national glory and show the superiority of Marx and Lenin. If that meant bending the rules, no problem.

In a time when the NHL’s professional players were barred from the Olympics, Russian pros were free to chase medals – the state officially considered them soldiers who played as amateurs. That rationale gave Tikhonov complete control over his players’ lives, since he was officially their officer and they were his soldiers. Using CSKA – the army’s hockey club – as the base for his Soviet national team, he could confine players to barracks, forcing them to train for much longer than their rivals from other countries.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, that all broke down. The system clung together for one more year to win a swansong Olympic gold, but its foundations had crumbled. In the late 1980s, Tikhonov had already been forced to keep some players out of the team for fear they might defect to the West in pursuit of the riches on offer in the NHL.

With the Soviet state gone, they were no longer his soldiers and they left the barracks, many going on to become legends of the NHL, such as Slava Fetisov and Pavel Bure. In cities like Detroit and Vancouver, they were the North American household names that Tikhonov, despite his glittering career, never quite became.

His passing is an opportunity to reflect on the passing of that Soviet sports system and how it influences Russia today.

The idea of sports as a means to achieve national glory is there in almost all countries, but it remains especially strong in Russia, where poor performances by a national team can still prompt furious denunciations by ministers and members of parliament.

That mentality was especially prominent in February as Russia topped the medal table at its home Winter Olympics in Sochi. In an echo of Tikhonov’s career, Russia was frequently strongest in sports in which its athletes depend on lavish government support and those from other countries often subsist on meager sponsor payments, but its hockey team of NHL stars failed to make it past the quarter-finals. Zinetula Bilyaletdinov became the latest in a line of Russian coaches who have failed to match Tikhonov’s feats in the six Olympics since his third and last gold medal.

But that’s not to say Sochi was a carbon copy of the Soviet sports mentality. Far from it. With a couple of exceptions, modern Russian coaches and the powerful Sports Ministry may have much more authority over athletes than in the U.S. or Britain, but it pales in comparison with the modern Chinese sport machine, let alone the Soviet Union.

Born in 1930 in Stalin’s Moscow, trained as a locksmith at the age of 12 during the Second World War, as a hockey player for the Air Force club, then as coach of the Soviet national team, Tikhonov lived his most of life in service to the Soviet state. While many of the ideas that permeated his career remain in modern Russia, most of the conditions that shaped him are long gone.

With Tikhonov’s passing, his methods and his many achievements move deeper into the realms of history.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox