Nikolai Miklukho-Maklai, Russian ethnologist who excelled in the studies of Oceania

RIA NovostiIn the mid-19th century when European expansionist power was at its peak, anthropologists and the scientific fraternity in the West circulated racist theories that attempted to justify slavery and colonialism. Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay, a scientist, who was born in what is now Russia’s Novgorod Region, was at the forefront of fighting these theories.

“Europeans only believed in liberty, equality and fraternity for other Europeans, while at the same time propagating ‘master race’ and ‘natural selection’ theories that said the people of color were meant to serve the white man,” says Dhara Wettasinghe, a Sri Lankan anthropologist, who studies the work of Miklouho-Maclay.

Miklouho-Maclay was inspired by Charles Darwin and worked as an assistant for the great German scientist Ernst Haeckel. “It was during his travels with Haeckel, who also held racist views, that Miklouho-Maclay vowed to disprove supremacist theories,” Wettasinghe says, adding that his kindness endeared him to people everywhere. “The inhabitants of Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, gave him his second surname, which roughly means a benevolent person.”

Miklouho-Maclay obtained his higher education, in fields such as humanities, medicine and zoology, in Germany. He met Haeckel at the University of Jena.

In 1866, when he was 20, the Russian scholar travelled with Haeckel to the Canary Islands for an expedition. “This trip had a profound impact on his life,” says Wettasinghe. “He travelled with Haeckel to several other countries before setting off on his own on expeditions to places such as Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia.”

While his mentor Haeckel believed that certain races were culturally backward, Miklouho-Maclay worked to disprove this.

In 1871, the Russian scientist moved to what is now called Papua New Guinea, becoming the first scientist to settle among and study people who had never seen a European. “His main objective was to make a comparative study of racial types in Oceania, but the experience reaffirmed his anti-colonialist stance,” says Wettasinghe.

Although the Papuans were initially puzzled to see a man with European features, they grew to appreciate the man who they believed came from the moon. Over the course of a year, Miklouho-Maclay formed close bonds with the people, who didn’t even know how to light a fire when he arrived, but already had complex social structures.

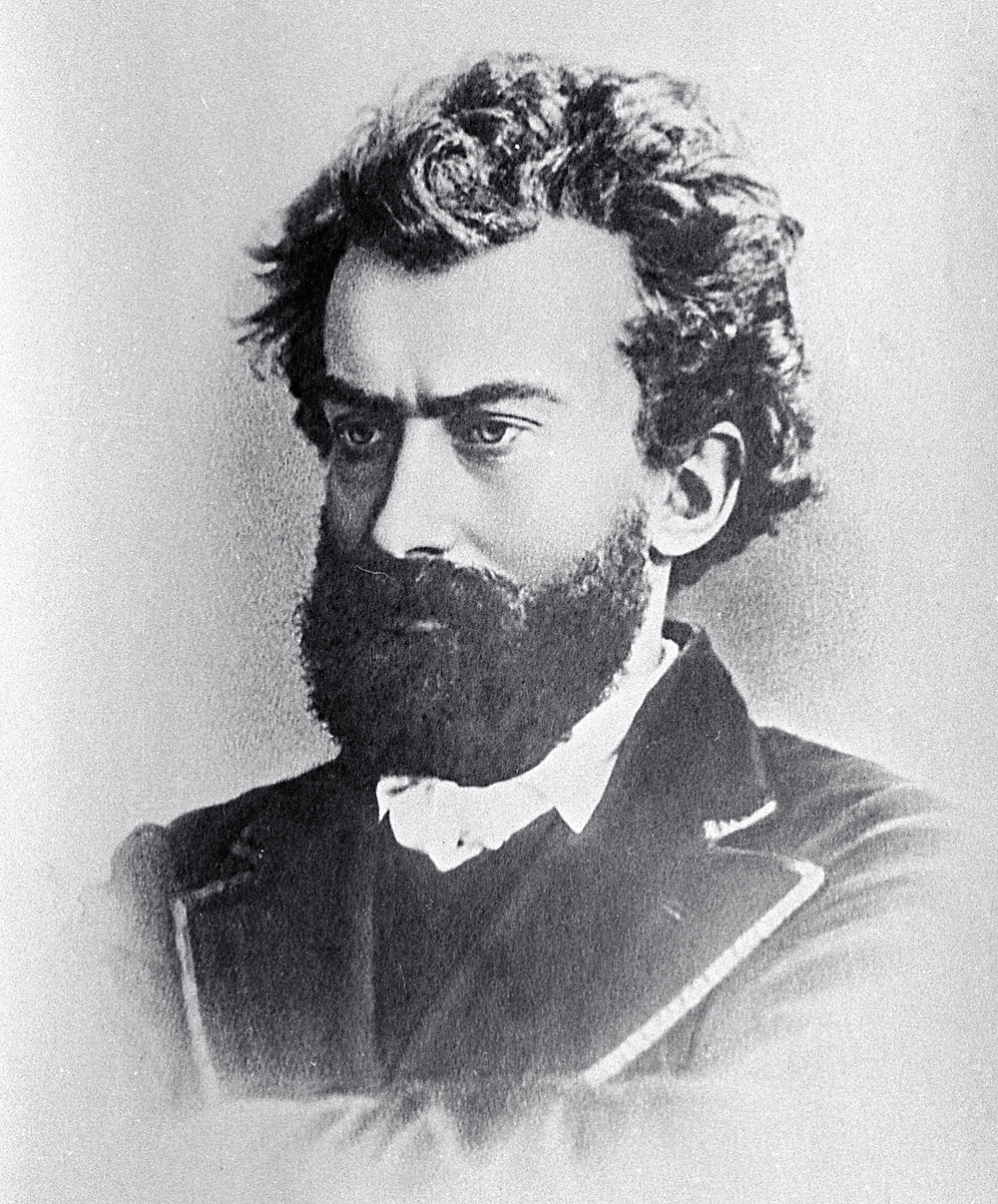

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay. Source: Wikipedia

Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay. Source: Wikipedia

He studied their language and customs and became a part of their society. The Russian scientist shared plant seeds with the Papuans, provided medical treatment and even helped to settle disputes between tribes. It is even believed that the Papuans were so attached to Miklouho-Maclay that they offered him a bride to stay back.

To this day, the Russian scientist is considered a hero in Papua New Guinea, where there are several monuments in his honor. The country’s northeast coast is called the Maclay Coast.

“There is no ‘superior’ race,” Miklouho-Maclay wrote after finishing his research in Papua New Guinea. “All races are equal because all people on Earth are the same biologically. Nations merely stand upon different steps of historical development. And the duty of each civilized nation is to help the people of a weaker nation in their quest for freedom and self-determination.”

A true polymath, his passion for biology stayed strong. In 1878, Miklouho-Maclay moved to Sydney, where he set up the country’s first marine biological research institute.

By that time, he was already a well know figure in Australia’s scientific community. “He published 34 research papers for the Linnean Society and was an honorary member,” says Wettasinghe.

The Russian scientist’s connections to Australia were cemented when he married Margaret-Emma Robertson, the daughter of the Premier of New South Wales. His descendants still live in Australia.

Right until his death, Miklouho-Maclay fought against slavery. It was his recommendations that led the Dutch government to stop slave traffic in the eastern part of Indonesian archipelago. He also fought for the land rights of the peoples of Papua New Guinea.

The Russian scientist went to St. Petersburg in 1887 to present his work at the Russian Geographical Society. He would never return to Australia. Miklouho-Maclay died in April 1888 of an undiagnosed brain tumor at the age of 41.

He earned the praise of both the scientific community and intellectuals such as Leo Tolstoy. “You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind, sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits,” Tolstoy said. “I do not know what contribution your collections and discoveries will make to the science for which you serve, but your experience of contacting the primitive peoples will make an epoch in the science for which I serve i.e. the science which teaches how human beings should live with one another.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox