Cabaret singer Maslennikova

Archive Photo Cabaret singer Maslennikova / Archive Photo

Cabaret singer Maslennikova / Archive Photo

The first official brothels opened in St. Petersburg in the middle of the 19th century. Medical and police committees were set up in 1843 to register prostitutes, and one year later a law on prostitution was passed. It regulated the living conditions in brothels and outlined the rights and obligations of their owners. By the turn of the century both the brothels and tastes in women had changed, but the fundamental system of this legal business remained.

The brothel keeper was a woman between 30 and 60 years old who resided in the brothel. The keeper's primary responsibility was to have her girls registered with the medical and police committees. She was also responsible for maintaining order in the brothel, as well as making sure that prostitutes followed the rules of hygiene and that the girls' papers were up to date. For her troubles, the madam took two-thirds of a prostitute's earnings.

Many madams abused the girls because of their disenfranchised status, often robbing them of their earnings. Prostitutes found themselves in virtual slavery and often were unable to leave because of the large debts to their madam.

After registering with the police, the prostitute’s internal passport was taken away and she was issued a yellow identity card, or ticket, hence this category name. The girls had frequent medical examinations, and worked in a specific brothel. Later in the 19th century, the authorities introduced strict accounting, enabling yellow-ticket prostitutes to officially make money and to shake off the madam's stranglehold on them.

Yellow-ticket prostitutes included both educated women, who spoke several languages, and completely degraded women operating in dirty and squalid dens and skid row bunkhouses.

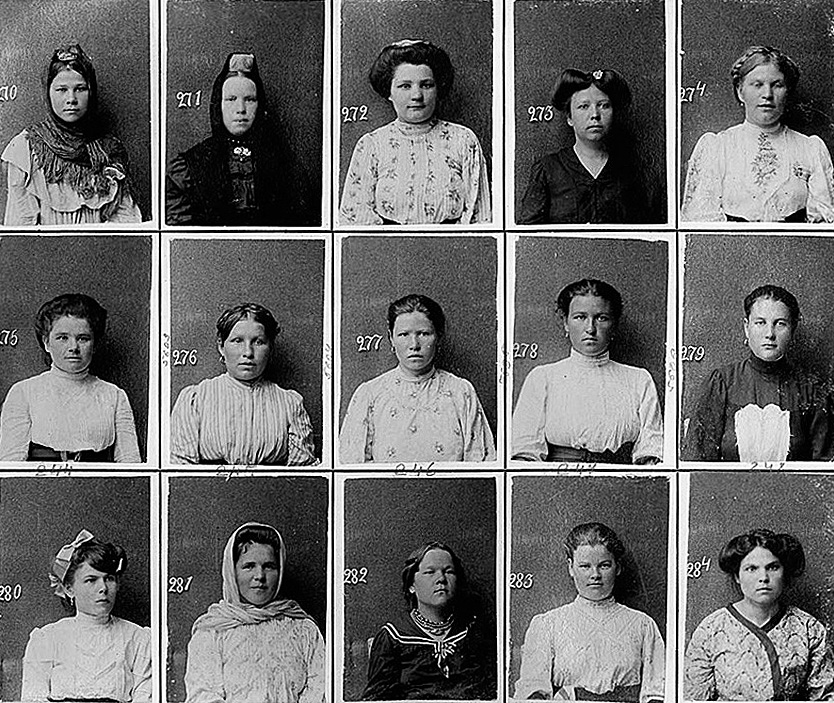

Prostitues in Russian Empire / Archive Photo

Prostitues in Russian Empire / Archive Photo

In his novella, Junior Captain Rybnikov, Aleksandr Kuprin described a top-rate brothel:

“This establishment was a cross between an expensive brothel and a luxurious club, with its smart entry, a stuffed bear in the lobby, carpets, silk curtains and chandeliers, and lackeys in frocks and gloves. Men would come here to end their night after the restaurants had closed. Here you could play cards, enjoy expensive wines, and choose from a wide variety of beautiful, fresh women, who would be rotated frequently.”

A solitary sex worker not associated with any brothel was known as a blank-sheet prostitute. For the most part these girls were caught in police raids and forced to register with the medical and police committees. They were issued special blank sheets, hence the name.

Blank-sheet prostitutes were the least secure of all sex workers. Not working in a particular brothel, they found themselves dependent on the landlord of their rented room, or were forced to risk their lives walking the streets alone on a nightly basis. These girls were frequently assaulted by criminals and psychopaths. In a series of violent murders in St. Petersburg in 1908-10, blank-sheet prostitutes were the main target.

Not all independent streetwalkers, however, risked their lives. There existed a subcategory of so-called aristocracy prostitutes, those who entertained their patrons in quality apartments. St. Petersburg newspapers in the early 20th century frequently ran advertisements similar to the ones below:

“A girl without a past, with an irreproachable reputation but without any means will eagerly offer all she has to anyone willing to lend her 200 roubles.”

or

“A young, merry girl who loves life and its delights would like to come in the service of an old man for decent remuneration.”

It should be noted that ordinary blank-sheet prostitutes were banned from the city center. St. Petersburg's Alexander Park had a scandalous reputation in the early 20th century. Most of the girls operating in the park had close links to the city's criminal underworld.

By the beginning of World War One, the number of St. Petersburg sex workers operating without yellow tickets or blank sheets had grown incomparably higher. These unofficial streetwalkers were often very young girls, and this secret prostitution market was under complete control of criminals.

Secret prostitutes did not undergo medical examinations, and therefore ran a much greater risk of getting infected with sexually transmitted diseases, which began to spread rampantly. Around 50% of all prostitutes had syphilis in 1910; by 1914 their share had reached 76%.

Prostitutes without blanks, detained by police. / Archive Photo

Prostitutes without blanks, detained by police. / Archive Photo

At the same time, child prostitution was thriving in St. Petersburg. Some girls were offering sex services in exchange for a box of sweets or a nice dress. They were controlled by adult female pimps, who often passed the girls off as their younger relatives. There were even brothels for those who preferred very young girls, sometimes just 10 years old.

By February 1917 the “liberating” revolution liberated morals, too. The medical and police committees were dissolved, effectively outlawing all prostitutes, who could no longer expect any help from the state.

Revolutionary Russia abolished prostitution as a profession that did not fit into the communist concept of a new, liberated woman.

This is an abridged version of the article first published in Russian by Arzamas Academy.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox