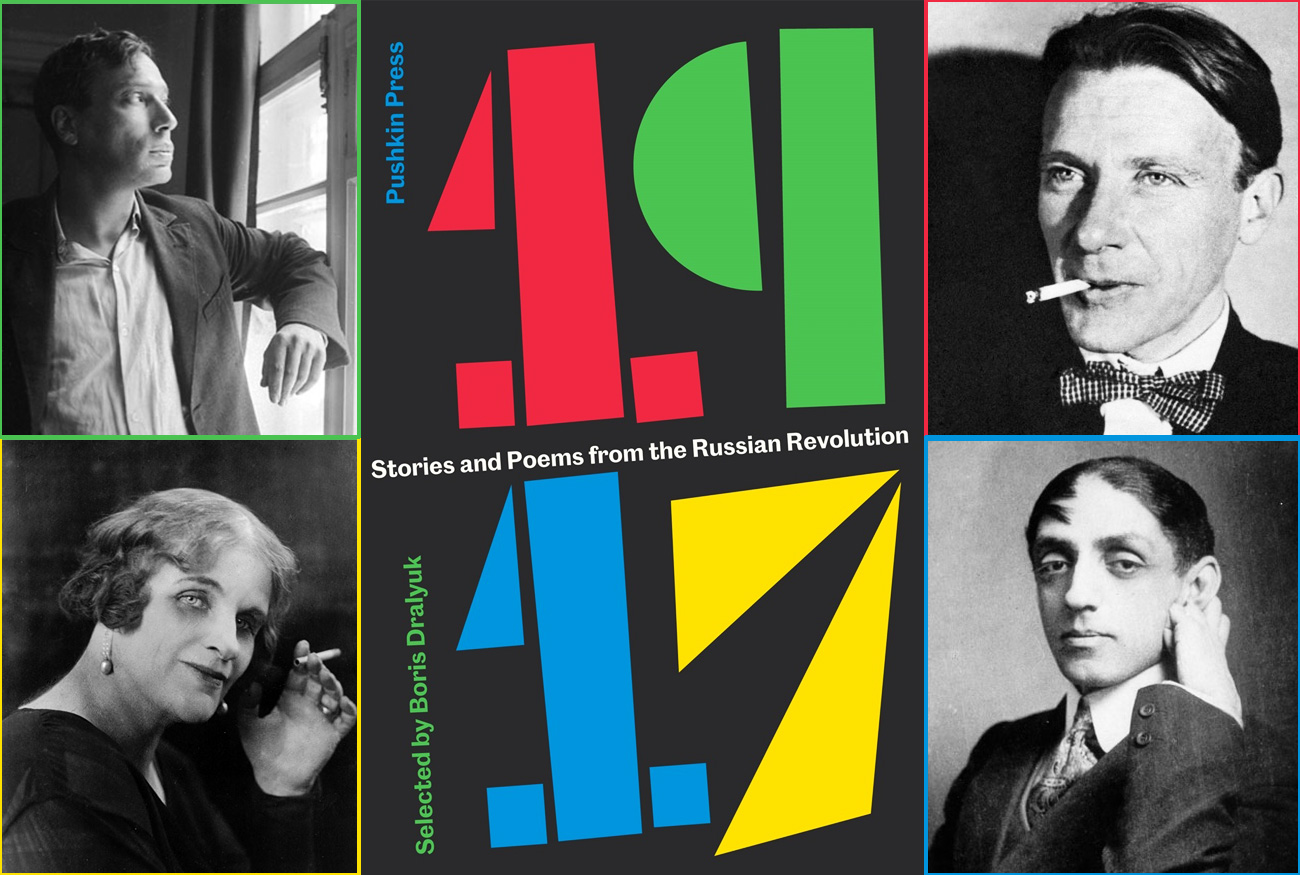

'1917: Stories and poems from the Russian Revolution' book cover. Clockwise around from left above: Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Bulgakov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Teffi (Nadezhda Lokhvinskaya)

Open sources '1917: Stories and poems from the Russian Revolution' book cover. Clockwise around from left above: Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Bulgakov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Teffi (Nadezhda Lokhvinskaya) / Open sources

'1917: Stories and poems from the Russian Revolution' book cover. Clockwise around from left above: Boris Pasternak, Mikhail Bulgakov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Teffi (Nadezhda Lokhvinskaya) / Open sources

A revolutionary book for revolutionary times. To some readers the moments of mayhem evoked in 1917, a brilliant new anthology, might seem strangely familiar. The sense of a world turned upside down, of peering into a sudden, vertiginous abyss, of violently divergent views and wildly differing predictions. One hundred years after the Russian Revolution this collection feels twice as timely. As the eccentric philosopher, Vasily Rozanov, wrote in The Apocalypse of Our Time, “everything has been undermined, everyone has been undermined.”

Boris Dralyuk. Source: Press photo Boris Dralyuk. Source: Press photo |

The poetry and prose in this new anthology was written between early 1917 and late 1919, and provides vivid snapshots of triumph and tragedy in those chaotic years. The collection opens with an unusually upbeat poem by Marina Tsvetaeva, and ends with Mikhail Bulgakov’s first published piece of work, a lament that asks, “What will become of us?”

In between, many less well-known authors add their conflicting – and often conflicted – viewpoints. Boris Dralyuk, translator and the executive editor of the Los Angeles Review, selected and edited the texts for the book, as well as translated some for his own. His aim is not to retell the history of the Revolution, but to recreate the “heady brew of enthusiasm and disgust, passion and trepidation that intoxicated Russia and the world as the events unfolded.”

The alcoholic metaphor is apt. In “Stolen Wine,” the opening section of 1917, Tsvetaeva (in Dralyuk’s translation) writes how raided cellars flooded every gutter, reflecting “a moon the color of blood.” Other writers are more hopeful. Boris Pasternak’s “Spring Rain” was written soon after the first revolution in February 1917, and it celebrates the energy of a collective chorus as the “surf of Europe’s wavering night” broke onto Russian streets. Poet Mikhail Kuzmin bursts joyously onto the page with “Russian Revolution,” exhorting readers to “Remember this – this morning after that black night,” conveying the “dizzying” sense of a world reborn.

Even language is reinvented by revolution. “Tough sandpaper has polished all our words,” writes Kuzmin, calling the revolutionaries “Renovators of language…” In Dovid Bergelson’s story, “The Red Train,” passengers wake to see a train “from the front – with a big red flag” and find they have no words left. “We look at one another mutely, as if learning to speak.”

The poems also reflect a disruption of form. Traditional lines struggle to hold extra syllables. Dralyuk comments that Tsvetaeva’s “half-sprung, half-reeling rhythm”, mirrors her “apocalyptic themes and imagery.” The brutal onomatopoeias of Alexander Blok’s “The Twelve” help balance this work on a strange, precarious ledge between stirring ode to revolution and elegy for a fragmenting past.

The prose in the second half of the book is often dynamically poetic. Alexander Kuprin’s “Old Story” of Sasha and Yasha, translated by Josh Billings, starts as dynamically as its protagonist -- “Nika the famous fidget. Nika the flea. Nika the nit. Nika who bounces around like a bucking nanny goat.”

Violence and uncertainty hide behind beguiling, child-like images -- a pilot who relies on a toy monkey, and a cadet who pretends he can play the drum. The unsettling strangeness of these war stories reflects their underlying ambiguity. A horrifying “true story” begins with a fairy tale image -- “By a sea of the deepest blue, at the foot of the green Crimean mountains, stretched out the tsar’s estate…”Translated from Yiddish by Michael Casper, Bergelson’s “Scenes from the Revolution” are glowing vignettes that encapsulate this sense of unease. The simple image of a red train, crossing snowy fields, contrasts with the “troubled hearts” of the watching passengers. Bergelson’s second, equally brief tale, conjures a “Bellybutton” dancing – grotesque and bestial – through happy crowds. The scene echoes Gogol’s disembodied nose, satirically roaming the streets of St. Petersburg, and prefigures Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog with its deep skepticism about the new social order.

In the center of this essential anthology are two pieces of characteristically sparkling prose by the satirist Teffi. Dralyuk calls her “one of the great, and most accessible, chroniclers of the tumultuous twentieth century.” Both sketches, translated by Rose France, feel disturbingly relevant today. The darkly comic dystopian vision of future bourgeois women queuing to be beheaded, in fashionable Marie Antionette wigs, symbolizes the ease with which social cataclysm can be normalized.

Teffi’s embittered essay, “A Few Words about Lenin,” mocks the incompetent infighting between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks that has obscured the “great idea of socialism.” Like much contemporary political farce, genuine stupidity outstrips parody. Teffi seems to speak directly to our times, warning us, amid the “triumphal procession of illiterate fools and willful criminals,” to listen to the wisest voices we can find.

Join the meeting with Boris Dralyuk at London's Pushkin House on Jan. 17 and at Sands Studio on Jan. 20. Read more>>>

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox