Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk.

Peter Kovalev/TASSFor the second year in a row, the Yasnaya Polyana literary prize, organized by the Leo Tolstoy literary museum and the Samsung Electronics company, has included a foreign literature category. Last year the prize went to the Japanese-American author Ruth Ozeki for her book A Tale for the Time Being. This year the prize of 1 million rubles (around $16,000) was awarded to Nobel Prize laureate Orhan Pamuk. He couldn't attend the ceremony in November because of his lecture schedule at Columbia University in the United States, so he came this February instead to receive his prize and meet with some readers. Following the ceremony Pamuk gave a talk with Fyokla Tolstoya, the writer’s great-great-granddaughter.

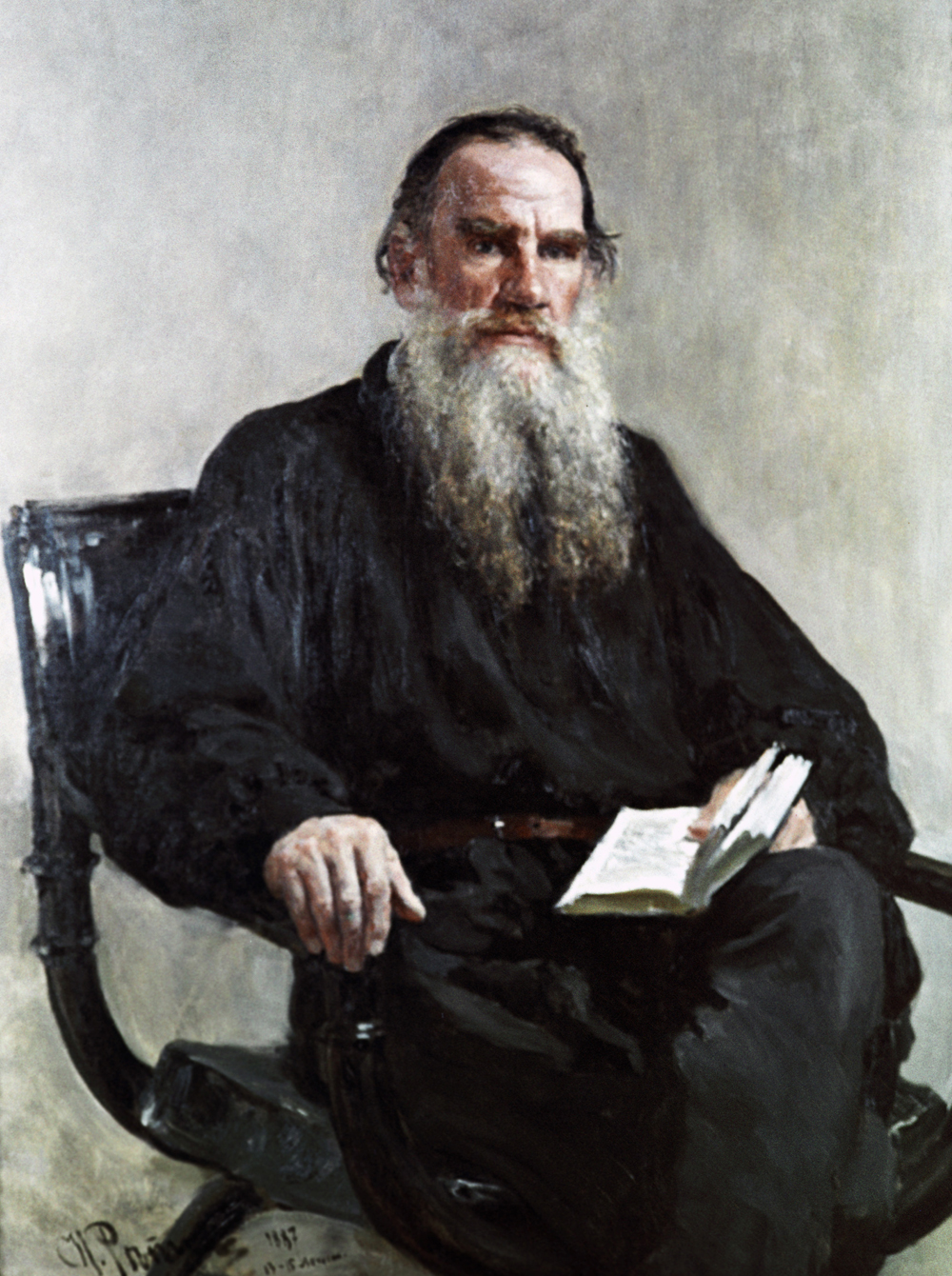

In his award speech Pamuk said that it was something he had “never even dreamt about” and that if you’d told him he would be in this position as a young man, he would have said “don’t make fun of me!” He went on to explain that when he was just starting out as a writer, he cut out and framed a picture of Tolstoy by Ilya Repin, so that the great man looked down on him from the wall as he wrote.

A copy of the portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ilya Repin from the collection of the State Pushkin Fine Arts Museum. / RIA Novosti

A copy of the portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ilya Repin from the collection of the State Pushkin Fine Arts Museum. / RIA Novosti

Pamuk first read Tolstoy when he was around 19 and is happy he waited until this age, explaining “I wouldn’t have understood all his depth earlier.” Now he knows Anna Karenina almost by heart and teaches it in his class at Columbia University.

“I think that Anna Karenina is the best novel ever written,” said Pamuk. “And Dostoevsky’s The Devils – sometimes is also translated as ThePossessed – is the best political novel ever written, so you Russians are lucky.”

Pamuk holds Tolstoy up as the gold standard of literature. “He gives us a sense of what life is like. When you read him you enjoy the details. I like the scene when Oblonsky eats with Levin in a restaurant. I’ve read it so many times: it reads so truthful, rings so natural, and isn’t pretentious.”

Pamuk also feels that Tolstoy infuses his novels with supreme values. Tolstoy has influenced him greatly and taught him “what is important in life.”

Pamuk doesn’t teach creative writing in his class at Columbia University. He feels that talented writers are able to feel their own way through the art. However, he does share some of the secrets he has learnt whilst writing his 10 novels (he is currently working on his 11th). For him, being a writer means talking about yourself in a way that people think it’s about others and writing the facts so that readers believe you have experienced what you describe.

“After my novel Museum of Innocence people asked me whether I had really fallen in love that strongly. I laughed and said that a writer shouldn’t reply either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. You want to tell the truth about how deeply you fell in love, but pretend it happened to your character – that’s the purpose of fiction.”

Pamuk also relates a legendary episode from when Nabokov applied to be a professor of Russian literature at Harvard. Slavic Professor Roman Jakobson was against the appointment, making the scathing remark, “What’s next? Shall we appoint elephants to teach zoology?”

Pamuk wants his students to see him as a writer first and foremost, not a professor, so he says “now I’m an elephant” and talks from an elephant’s point of view.

Many of Pamuk’s novels are historical, and he is currently working on an historical novel that begins in 1900 in the Ottoman Empire. He is carrying out a great deal of research through reading memoirs. However, as he explains, historical fiction doesn’t have to be totally accurate.

“Each historical novel creates its own criteria for accuracy. Take Tolstoy, for example – he is sometimes accused of not being accurate, but it is easy to forget that he was writing many years after the fact. International reader in particular forget that he was writing an historical novel, not a history book, and some 50 years had passed since the events he described.”

Following the talk, many readers asked Pamuk what he reads and would recommend. “In my view, the greatest writers ever are Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Thomas Mann and Marcel Proust,” he said. “I have also been influenced by Borges, Italo Calvino and Vladimir Nabokov.”

“He would look around and say, ‘Wow, there are so many windows, so much bouza to sell here, but the buildings are so high: how can you shout ‘bouza’ loudly enough for them to hear it up at the top? Mevlut is a successful bouza seller because the buildings in Istanbul were only around 2-3 floors high.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox