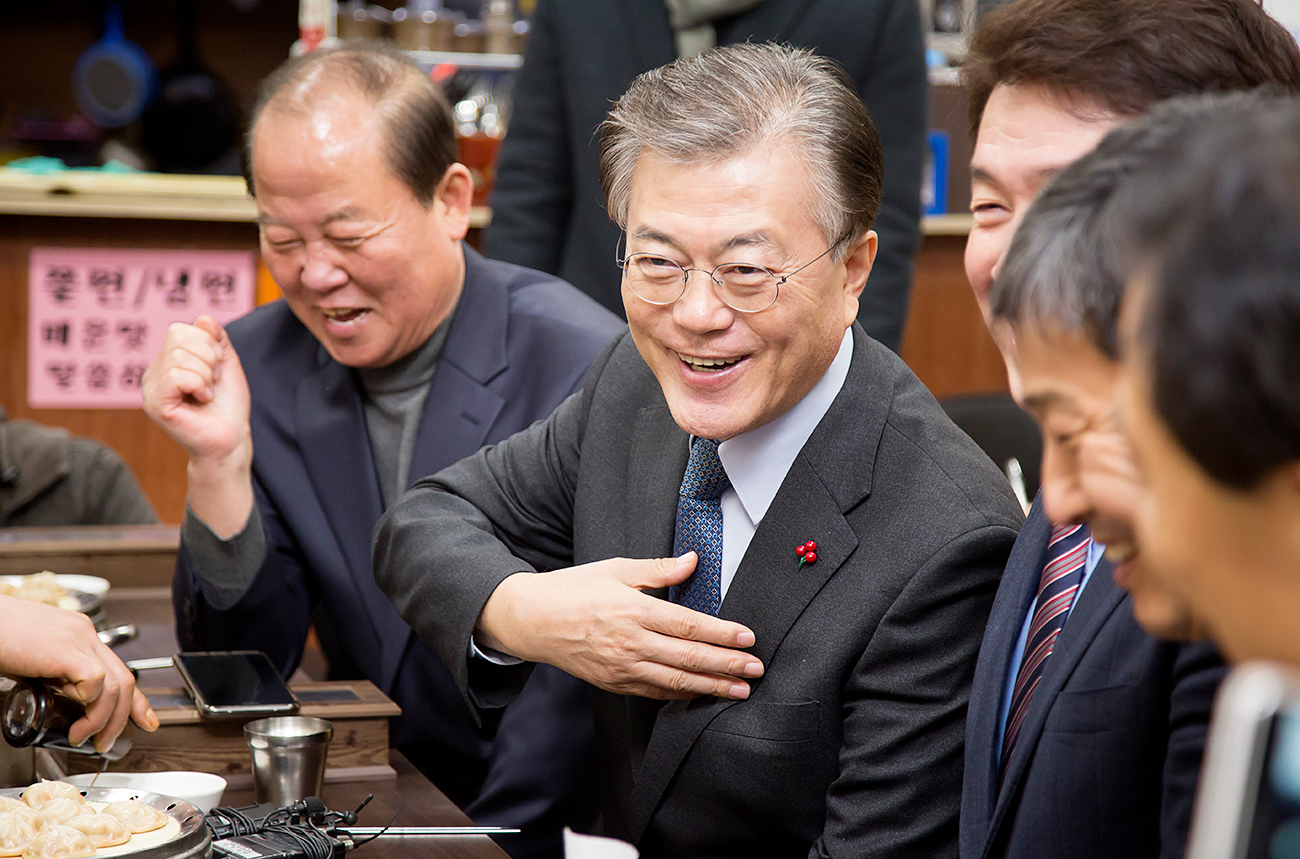

Moon Jae-In (C) has a good chance of becoming the next South Korean President.

AFLO/Global Look PressOfficially the election campaign in South Korea has not yet begun but in reality, it is a common feeling that President Park Geun-hye will be removed from office and elections will be held in the spring of 2017.

Despite the fact that the situation remains dynamic, and political forces are actively working on building new alliances and blocs, the main contenders for the post are already known. This allows us to make assumptions about which Korean politicians would be most favorable for Russia.

Every election in South Korea is a confrontation between the country’s two major ideological forces: the conservatives and the so-called South Korean progressives.

The conservatives support a hard line in relation to North Korea and are believed to follow the U.S. foreign policy. The ruling Saenuri Party, President Park Geun-hye and her government belong to this group.

Although South Korea's progressives are not planning to break their alliance with the United States, they are trying to build a more or less independent foreign policy.

The most obvious difference between the conservatives and progressives is seen in how they view their policy towards North Korea.

To make it short, the progressives are more likely to actively develop cooperation with Pyongyang or at least try to act in this direction.

There are 5 or 6 potential candidates for the presidency of South Korea. The main favorite is the representative of the opposition progressive camp - Moon Jae-in, 64.

In the last presidential election he lost to Park Geun-hye by a small margin, and now has a very good chance of taking revenge, if early presidential elections are announced.

According to surveys conducted on Feb. 1-2, Moon Jae-in may win the presidential election by a margin of up to 30 percent or more from his closest rivals. This is a giant gap by the standards of South Korean politics.

“The second echelon” comprises of politicians from various camps whose ratings vary, according to the latest survey, in the range of 7 to 10 percent. Their exact positions may vary each week, so there is not much sense in building an accurate hierarchy.

Among them are South Chungcheong Province Governor Ahn Hee-jung, 51, Seongnam Mayor Lee Jae-myung, 52, one of the leaders of the opposition People's Party Ahn Cheol-soo, 54, and the Prime Minister and currently acting President Hwang Kyo-ahn, 59.

The first two are ideologically in the same camp as Moon Jae-in, although they occasionally criticize him.

Successful businessman and university professor Ahn Cheol-soo is also from the opposition, but has recently begun to shift from the progressive camp in the center, trying to attract conservatives.

Prime Minister Hwang has never declared an intention to participate in elections as a candidate, but in any case he is clearly a conservative.

Prior to Feb. 1, there was another major player, who was considered the main rival to Moon Jae-in. Ban Ki-moon, who on Jan. 1, completed his term as the UN Secretary General, returned to Korea and became actively involved in the election campaign.

He was consistently in second place after Moon Jae-in, judging by the polls, but quite unexpectedly announced his decision to withdraw from participating in the elections.

The precise reasons can only be guessed, but, as experts believe, a combination of factors may have played the role: corruption scandals involving his family, underestimating the realities of Korean politics, and also realization that the gap with Moon Jae-in continued to grow.

It is widely believed that potential voters did not pay heed to the Ban Ki-moon’s ideas of “a united nation” under his leadership.

Former UN Secretary General clearly gravitated to the conservatives, although he expressed the desire “to unite all without distinction of political views, and regions.” However, Ban Ki-moon has ‘fizzled out.’

The Russian factor does not play any significant role in the election platform of any candidate, and if an “expert on Russia” appears among advisers to politicians, this role is often laid on those who have a very rough understanding of Russia.

Russia is primarily remembered when there is a discussion about solving the North Korean problem.

The main topics that foreign policy platforms of potential presidential candidates are built on are the relationships with the United States, China, Japan and North Korea.

The most favorable South Korean President for Russia can be judged, for example, by what the candidates think about the placement of the THAAD system on the peninsula. Another area that can directly affect Russia’s interests is the North Korean policy vector of Seoul.

With these limitations in mind we can say that the progressive camp may be the most “suitable” for the interests of Russia.

The current favorite in the presidential race, Moon Jae-in, consistently advocates to at least postpone the deployment of missile defense systems of the United States in Korea. Seongnam Mayor Lee Jae-Myung agrees with him.

It is noteworthy that even a representative of the progressive wing of Ahn Hee-jung believes that Seoul, which has already signed an agreement on the deployment of missile defense systems of the United States, should comply with the signed agreement. He, however, calls for a dialogue with Russia and China to avoid a conflict.

On the other hand one must admit that Moon Jae-in has already begun to move in the direction of THAAD deployment.

Progressives are also more ready than conservatives to intensify their dialogue and further economic cooperation with North Korea.

Again, this is in the interests of Moscow, which, although does not approve of Pyongyang’s nuclear blackmail, still believes that problems should be solved with negotiations and not just through pressure and sanctions.

In addition, inter-Korean cooperation would give an impetus to the Russian-North Korean projects that Moscow always wanted to connect with Seoul as well.

These include the Hasan-Rajin logistics project, possible proposals for the supply of gas or electricity from Russia to South Korea via its northern neighbor, as well as a railway connection.

As Russia does not play any significant role in South Korean domestic politics, Russia’s sole hope is that Park will be replaced with someone who would be a little easier to work with.

Despite the clear differences on the question of the U.S. missile defense system and the North Korean issue, and a certain amount of stagnation in relations, Russia and South Korea under President Park Geun-hye have managed to avoid conflicts.

After the U.S. and Europe gave hints about softening anti-Russian sanctions, South Korea began to actively look to invest more in Russia.

There are many challenges in this area such as political problems, identifying mutually beneficial areas and improving Russia’s investment climate. Unless these problems are addressed, there’s little that a new South Korean President can do to improve economic ties with Russia.

Oleg Kiryanov heads Rossiyskaya Gazeta's Asia Bureau in Seoul

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox