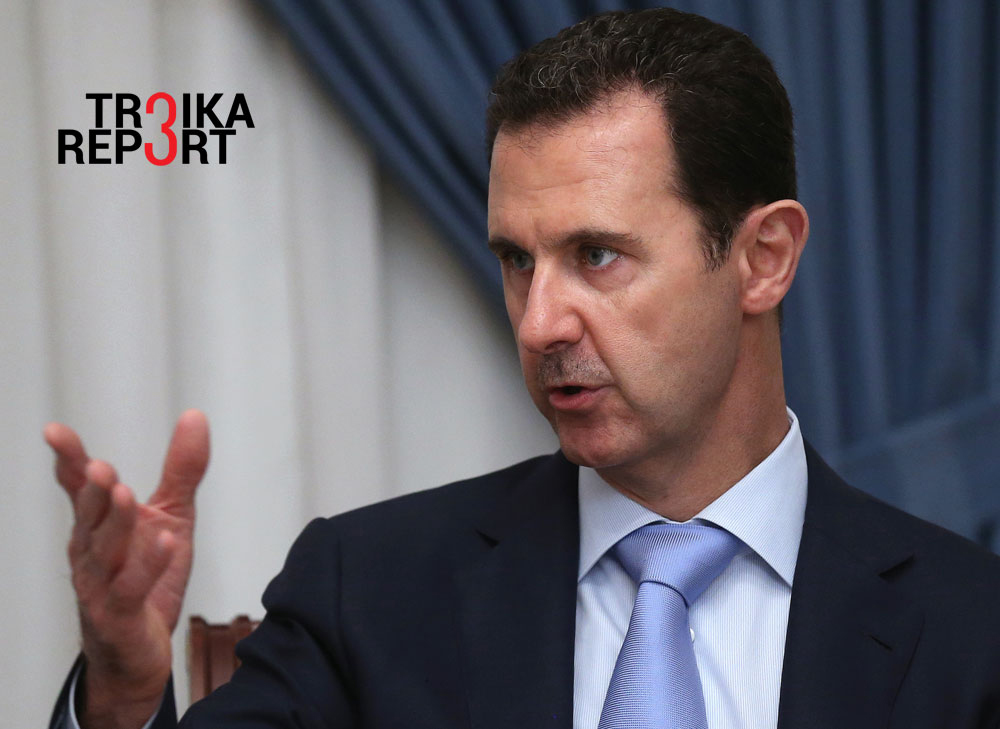

“Bashar al-Assad will not necessarily play by the letter and spirit of the ceasefire agreement," Russian pundits said

Valery Sharifulin/TASSThe accord on a ceasefire in Syria, due to enter force on Feb. 27, raises as many questions as it provides answers.

Brokered by two main stakeholders, Russia and the United States, and reportedly endorsed by the regime in Damascus and by at least some factions of the opposition, the same opposition that has been poised for more than four years to topple Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, the deal is haunted in the public domain by three sentiments: the cautious optimism of the diplomats, the skepticism of the experts in Arab world affairs, and the cynicism of the adversaries on the battleground.

The course of negotiations of the ceasefire was something of a roller-coaster, with its ups and downs. All throughout the inevitable horse-trading and secret deals around the talks, the Syrian army, under the cover of Russia airstrikes, continued its advances.

On the one hand, the military gains of the regime of Damascus narrowed the scope of manoeuvre for the Syrian opposition, leaving them without “strategic depth” for a dignified retreat. But pinning against the wall those regarded as a bona fide negotiating party was no good either since it could force the opposition into fighting to the very end.

On the other hand, the de-blocking operation targeting Aleppo made little distinction between an assortment of paramilitary formations belonging to either moderate Islamic or radical Islamist groupings that for years had besieged the strategic city in the north of the once unified country.

For the regime of Bashar al-Assad, any delay in the more or less smooth retake of the lost occupied territories could become a setback, slowing down the pace of the offensive, and providing breathing space for his enemies, who would use it to regroup, rearm, replenish ammunition stocks, and then strike back.

Moreover, any ceasefire is the very beginning in a sequence of events, the interlude to a prolonged process. It is sort of a merry-go-round because each and every term and condition of a final settlement has to be regularly “revisited” for the purpose of monitoring whatever progress has been made and specifying the ways to deal with the new challenges that emerge.

Grigory Kosach, an expert on the politics of the Arab world and professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities, assessed the feasibility of turning the ceasefire deal into a launching pad for a transitional political process in Syria in comments made to RBTH:

“Bashar al-Assad will not necessarily play by the letter and spirit of the ceasefire agreement. He has just announced that he will hold parliamentary elections on April 13, which does not seem to bode well with the existing agreements,” he said.

Kosach refers to the road map approved in November by world powers, which stipulates a six-month period to conduct Syrian talks aimed at producing a consensus among the warring parties to change the constitution and hold free elections within 18 months.

However, he also pointed out that there was no real sign that Riyadh was taking the issue of a ceasefire seriously.

“I scanned through most of the Saudi Arabian dailies the day after the ceasefire announcement and in the wake of the traditional Monday meeting of the government presided over by King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud. There was not a single mention of the agreement to hold fire. As long as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf monarchies do not sign up to the deal, its actual worth is subject to serious doubt.”

In other words, despite signatures on the ceasefire accord, nothing is set in stone yet – the implementation of the agreement may run afoul.

Meanwhile, in a speech marking Defender of the Fatherland Day, the annual celebration of Russia’s armed forces (also viewed as the day of manliness and masculinity), Russian President Vladimir Putin committed his foreign policy to convincing and persuading Russia’s allies in the region to observe the ceasefire.

Putin expressed hope that the United States would do its bit by influencing regional actors close to its foreign policy orbit to do the same.

These might be the right tactics. But with Washington’s credentials as the long-term security provider in the Middle East considerably undermined, it is not a given that the Sunni kingdoms will lend Washington an eager ear, as they did previously.

This is not the only minefield ahead. With the incumbent president Assad, still cornered and harbouring often-murderous wrath, Moscow could find itself in an awkward position. On this point Kosach strikes the nail on the head: The Syrian president is a tough cookie, and we might well see the “tail wagging the dog.”

Like the Bull of Baghdad, as Saddam Hussein was known, the embattled strongman of Damascus may pursue a hidden agenda, despite being sincerely thankful to Moscow for turning the tables.

Moreover, any foundation for an inter-Syrian dialogue to bury the hatchet of sectarian hostilities requires meaningful compromises by all sides. Yet how can this materialize when there is still misunderstanding on who can be called a “moderate” Islamist?

Then, if financial donors of the Syrian opposition and those regional powers that are arming and guiding local jihadists decide to derail the ceasefire, they have a plethora of capabilities to do it.

For the moment, the negative factors seem to outweigh the positive gains, but this discouraging forecast can hardly be dismissed as the result of brooding over exaggerated bad omens while reading leftover coffee grounds somewhere in Ankara or Riyadh.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox