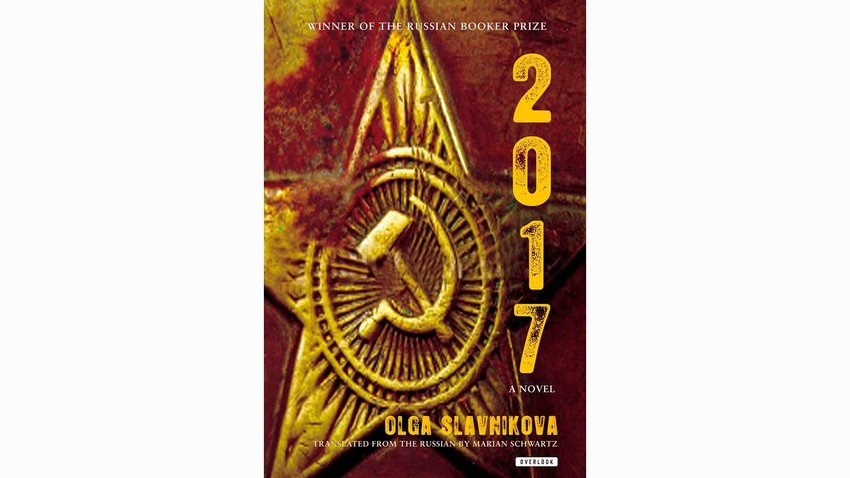

In the mythical Riphean Mountains, gem prospectors, called rock hounds, search for precious stones. On the streets of a Russian city, romance unfolds against the backdrop of the centenary of the 1917 revolution—seemingly a call to repeated violence. Olga Slavnikova weaves these parallel plots and settings together in “2017,” an ambitious, postmodern contribution to a revered literary tradition. Slavnikova’s strange, genre-defying novel, winner of the 2006 Russian Booker Prize, finally made it into English in Marian Schwartz’s luminous translation.

There is a great heritage of Russian Sci-Fi, most of it decidedly dystopian. George Orwell borrowed shamelessly from Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 “We”. Several recent novels have set their action a few years in the future to create a satirical alternative present: Tatyana Tolstaya’s “Slynx” and Dmitry Glukhovsky’s “Metro 2033” use post-apocalyptic scenarios.

Slavnikova flirts with the sci-fi genre. She winks at rejuvenating nanotechnologies, flashes a few holographic toys and flutters some comic predictions: a female American president with a multiracial rainbow of adopted kids; a fashionable nightclub with an “erotic striptease based on Dostoevsky’s plots.” A more serious prognosis is found in ecological catastrophe, springing from human greed and carelessness, which is poisoning the mineral-rich Ripheans (reminiscent of Slavnikova’s native Urals).

The anniversary of the revolution reinforces the idea of a recurring national destiny. Many 19th-century Russian artists embraced a rebirth of folk art and Slavic heroes. For Slavnikova, this stylistic nostalgia created an “historical dreaminess in their weak and impressionable heirs.” History becomes a virus and then an epidemic, spreading finally to Moscow where the toppled monument to murderous security chief, Felix Dzerzhinsky, is resurrected. The novel coasts close to reality here since Moscow’s former mayor suggested just such a reinstatement in 2002.

Slavnikova imagines a fake, but bloody civil war, as inevitable as it is inauthentic. The striving for authenticity, rejecting the superficial sparkle of wealth and the “culture of copies,” is a keynote of the novel. This is not an exclusively Russian problem, but part of a “terrible, global passivity.”

The protagonist, a gem-cutter called Krylov, relishes the transparency of quartz; his polishing is an attempt to reveal what he sees inside. Despite this background in a lovingly-depicted trade, Krylov’s aimlessness nudges him towards the ranks of Russian literature’s famous superfluous men. In fact his ex-wife, Tamara, declares that most of the human race is now superfluous, irrelevant ‘to the economy and progress.’ Tamara runs a funeral business that profits from reinventing ‘the worst kitsch Russian commerce had to offer’; she even offers her clients a lottery where they can win a Caribbean holiday.

The women in Krylov’s life are disappointingly allegorical. Tamara is fleshy and glamorous, worldly and cynical, while Krylov’s lover, the mysterious Tanya, is slim and spiritual. Krylov and Tanya’s poignant and fragile relationship recalls that of Anna and Dmitry in Chekhov’s “Lady with a little Dog” mixed up – in this case - with a spy thriller. Tanya is a frustratingly elusive character, identified with the legendary “Stone Maiden,” one of the rock spirits who occasionally threaten to lead the novel veering off into the thickets of magic realism.

Deep-rooted paganism and folklore are just two of the facets of Russian culture the book begins to explore. “2017” is packed so full of ideas and images it sometimes threatens to explode under the pressure. Its strength is in its linguistic subtlety and ingenuity. The opening chapters are dauntingly long-winded, but – like the Riphean Mountains – these dense hills of text hide invaluable riches.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox