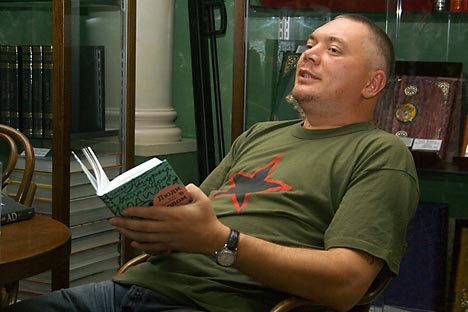

German Sadulaev. Source: PhotoXPress

There are so many things wrong with “I am a Chechen” as a novel. There is virtually no plot and barely anyone who could really be described as a character, apart from fleeting cameos by murdered friends and childhood memories. Even the narrator is a fluctuating presence, while “mama” turns out – more often than not – to refer to the fields and woods of Chechnya itself. German Sadulaev’s fragmented meditation on war, identity and rootlessness is an uneasy mixture of fictionalized memoir and painful lament.

The style is also unreliable, veering wildly between brutal war-time horrors, purple passages of swallows and wildflowers, and historical background information. The self-conscious descriptions of the Chechen landscape are embarrassingly full of phrases like “the breast of our motherland” and over-extended metaphors involving “the scarlet cow of the sun” wandering into the “blue pasture of the sky.”

Despite all these caveats, this is an important and sometimes moving book. The underreported war between Russia and Chechnya needs storytellers who are not serving “either side’s propaganda system,” both of which foster an image of “the Chechen as an enemy of Russia.”

Sadulaev was born in the Chechen village of Shali and moved to Leningrad in 1989 to study law. He still works as a lawyer in St Petersburg, but his personal connections with Chechnya make it impossible to write dispassionately. He often overtly challenges the reader in the novel itself, writing, “I know: it is disjointed, sketchy … There is no central plot. It is hard to read prose like this, right?”

In the end, the visceral nature of Sadulaev’s stream-of-consciousness is as much strength as weakness. The reader is caught up in an emotional outpouring, which editing might have rendered distant or clinical. In his novel, he compares his own writing to “spurts of blood” or to the cluster bombs, banned by the Geneva Convention, whose flechettes embed themselves in the heart of the girl next door.

At one point, Sadulaev compares the documented cases of post-Vietnam suicides with the unnumbered young men in Russia who have killed themselves after active service in Chechnya. “And these were the best of soldiers,” he writes. “There are others … they too have returned.” The message, ultimately, is simple: “We have to conquer evil, to rise above hatred.”

Sadulaev’s Russian publisher in 2006 was the controversial Ultra Kultura. Founder, Ilya Kormiltsev described himself as “a conscious opponent of the present-day Russian political system.” His publishing house was closed down in 2007 when he moved to London, where he died of cancer. In a piece for Vintage Books last year, Sadulaev cited the murder of Anna Politkovskaya and wrote: “There is no formal censorship, but is there freedom of speech?”

There is a fine tradition of Russian writers, including Lermontov and Pushkin, who celebrate the beauty and bravery of the Caucasus. Tolstoy’s “Hadji Murad” opens with the symbol of a crimson thistle. Broken by a cartwheel but “risen again,” the thistle refused to surrender to humans, who “had destroyed all its brothers around it.”

Among recent accounts of the battle-torn region, Arkady Babchenko’s “One Soldier’s War” is the outstanding example. A glimpse of the Chechen perspective is a rarity, especially in English. Sadulaev, like Tolstoy’s thistle, has seen friends and family perish in a brutal conflict. He is wracked with guilt about not having been there: “I should have died.” But the friends that died will never get to write about it; “that’s why I … - the one who remains – write this book.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox