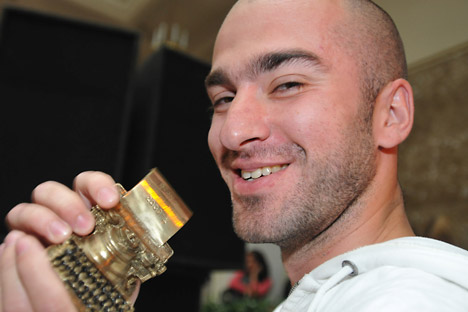

Russian writer Alexander Snegirev. Source: ITAR-TASS

A young and promising architect who depends heavily on his own parents finds himself a lonely single father after a freak accident. His teenage son Vanya, who has Down syndrome, comes home lugging a painting of a woman covered in oil, called the “Petroleum Venus.” Improbable coincidences lead the two to the painter, the painter’s two daughters and, eventually, more significant characters. The biggest surprise is the protagonist of his novel, who, despite a successful career, very willingly turns away from his glamorous lifestyle and long-legged girlfriend to raise his handicapped child by himself.

|

| A cover of "Petroleum Venus" |

This somewhat bizarre modern-day fairytale, despite its unlikely twists and turns, reads easily and quickly, narrated in a simple, unpolished voice. When I meet author of the novel, Alexander Snegirev, at the Read Russia stand at Book Expo America 2012 in New York, I find it easy to imagine that he modeled his protagonist on himself. Snegirev, 31, is the same age as his character, tall and smartly dressed. Although Snegirev is a little reserved, you feel a strong, inherent gentleness in him.

Snegirv’s career blossomed quickly after winning the Debut Prize for young writers in 2005. Having no connection in literary circles, he was skeptical of his own chances but sent in several short stories, thinking he had nothing to lose. The prize put him in the limelight, journals began publishing his prose and two years later, a novel, “How we bombed America,” was published.

The author himself hadn’t expected to make a living in literature – he studied architecture first before becoming disenchanted by its emphasis on mathematics rather than art, and switched to political science. He does not come from a literary family, either, though he mentions his grandfather, an accomplished “writer” of complaints. “He was good at writing official letters to the authorities. Apparently he wrote complaints so beautifully that they kept agreeing to his demands and raised his pension.” On a more serious note, he credits his father for instilling in him a love of stories. “I was four when he started reading fairy tales to me. And to teach me to read and write, my father started writing me letters from Petrushka, the hero of the fairy tale. I believed it, and I started writing back to Petrushka – my father helped me, and we would leave the letters in my box of toys for exchange.” He regrets that these letters were lost, and says that this experience taught him the basic procedure of reading and writing – he was always thinking about what and how to write so that Petrushka would enjoy reading his letters.

Although he jokes that he writes in a simple language because he cannot write in a complicated way, Snegirev considers his main task as a writer is to be a filter – the end product, his prose, should be pure, simple and clear. “And to write a simple and clear story, a lot gets thrown out,” he says. Used to writing for his own pleasure, it took him a while to see his own writing as literature, or to think about who his readers are, what they think about him. “I write what I would like to read myself,” he said. “To be honest, it’s a matter of self satisfaction; of writing what would give me pleasure to read. If there’s something you would like to read but you haven’t read it yet – write it yourself.”

He has just finished writing a novella about a young man who discovers that his grandfather was once a member of the notorious NKVD under the Stalin regime—one who killed civilians. Accustomed to thinking of such people as monsters, the protagonist is unable to accept the fact that he himself is related to such a monster and as a kind of trauma suffers a split personality. The plot examines recent history; and the issue of Stalin’s legacy is one that divides Russians to this day, Snegirev said that the theme of inheritance is something everyone can relate to. “It’s the struggle of every person. “Every man, no matter what his relations are with his father, rebels a little against becoming like his father.”

In “Petroleum Venus,” the mentally challenged Vanya is free of the typical rebellion from his father. Vanya does what he wants – he picks up a painting from a car crash site if he wants, he asks to wear lipstick, and in the most absurd scenes (of which there are many), he is the only one who is not confused and upset. His father learns a lot more from him. In many ways, Vanya is the yurodivy (holy fool) of the novel; the light that illuminates people’s follies and makes people reflect.

“Petroleum Venus,” translated in English by Arch Tait, will be available in February 2013.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox