Hamid Ismalov: 'Any writer who writes in Russian is a Russian writer.' Source: Personal archive

Uzbek writer and journalist, Hamid Ismailov fled Uzbekistan in 1992. He eventually found himself in London, where he works for the BBC World Service. Here he talks to RBTH about life, literature and the need to accept otherness.

Russia Beyond The Headlines: Can you explain why you were forced to leave Uzbekistan in 1992?

Hamid Ismailov: There was a threat of my imminent arrest. The Uzbek government didn’t like the political writing I had done as a correspondent for Literaturnaya Gazeta.

I was summoned to the police and they opened a case against me so I had to leave. I went to Moscow and then to France. I left my daughter in Tashkent (she was twelve at the time) and I still have her letter saying: “don’t come to pick me up because the prosecutor’s office is coming round every day.” This was 20 years ago.

RBTH: So you went to Moscow and then France? How did you end up in London?

H.I.: Yes, we were hiding in Moscow. One friend of mine – a top guy in the writers’ union – told me they had sentenced me to death in Tashkent so I was hiding in friends’ flats, living the life of Salman Rushdie. I had a year in France on a scholarship and then stayed in Germany, again with friends. The BBC found me there in 1994 when they were setting up their Central Asian Service.

RBTH: Earlier, you lived in Moscow, from 1984 to 1992. What influence has Russian culture has had on you? Do you see yourself as a Russian writer?

H.I.: Russian literature is in my blood. I read a lot of contemporary Russian literature and I often write in Russian. I started to write my novel,

“The Railway,” in Uzbek, but one publisher said it would never be published there so I rewrote it in Russian.

Any writer who writes in Russian is a Russian writer. Russians have always had different ethnic origins. Pushkin had Ethiopian roots and Russia is an ethnically diverse country.

RBTH: Your novel “The Railway” was translated by Robert Chandler and published in English [by Harvill Secker] in 2006. It’s set partly in 20th century Uzbekistan and evokes the old silk route, now a railway, as a way to look at the history of Central Asia. How did you come to write this novel?

H.I.: This novel was set during the Soviet times and I was thinking about that time and that there were many different national literatures all talking about themselves, but none of the reality of the melting pot, which had existed all around me since my childhood. This reality was missing in literature so I decided to recreate it.

In one of my sleepless nights in Tashkent in 1992, I tried to remember each house on the street where my granny lived when I was a child and I realized that what I considered an Uzbek neighborhood was completely different. There were Mordva, Chuvash, Tartars, Jews, Gypsies, Koreans, Tajiks…

In writing the novel, “The Railway,” it was hard to find a main character. You have to give a voice to everyone. Everyone has a story to tell and a voice in the choir of these nations. The novel was considered a representative of postmodernism although I had never intended to write a postmodern novel. It was very widely reviewed and there was even a review in the “Big Issue,” which I was particularly proud of.

RBTH: Apart from the fact that it’s a wonderful book, do you think there were other reasons why people paid your novel so much attention?

H.I.: I think it was high time for people to learn more about Central Asia. In 2005, there was a massacre in Uzbekistan so the country was in the headlines for a while.

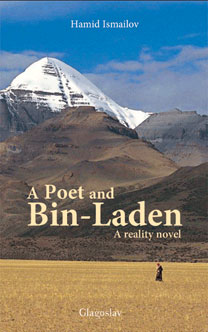

RBTH: Your latest novel in English, “A Poet and Bin-Laden” [translated by Andrew Bromfield; Glagoslav 2012], looks at more recent Central Asian history and combines documentary, poetry and fiction. What made you choose such an experimental form?

|

| By Hamid Ismailov, Glagoslav, 2012 |

H.I.: The novel is about a poet who ends up with the Taliban. In his manuscript, which forms the second part of the novel, there is a story about two Mughal brothers. It’s a story of fratricide and the conclusion is that radicalism of any kind always finds its own otherness. It is not about a clash of cultures; if the Americans all disappeared tomorrow, these extremists would kill each other. If you are a radical like this, even your own otherness becomes your enemy.

So, the documents in the first half of the novel are the raw material from which Belgi, the poet, creates the quintessential literary form: the story about fratricide, a symbol for radicalism which never stops finding otherness. Either you accept otherness in whatever form or you don’t and you fight it. This is what the novel is about.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox