Sakhalin Island through the eyes of Chekhov & now

In 1890, Anton Chekhov undertook the tedious journey to Sakhalin, even after knowing that he was ill with tuberculosis. “Hell,” was how he described the island, where the Tsarist regime established a penal entrenchment colony.

During his 3-month stay, he witnessed whippings, confiscation of meagere supplies and forced prostitution of women Sakhalin Island, Chekhov’s single largest work, is more a journalist account than literature and brings to the reader’s attention, the horrors of life in a giant 19th century prison colony.

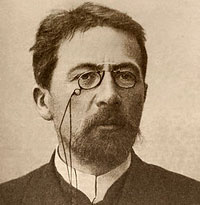

Osip Braz. Portrait of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (1898)

wikipedia.orgIn 1890, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov did not have the luxury of an 8 hour 40 minute flight to far-off Sakhalin Island from Moscow. In his two and a half month journey through Siberia, the great writer used various modes of transport including trains, ferries and horse carriages to get to the island, then a penal colony.

Just 7 kilometers separate the westernmost point of Sakhalin from the Russian mainland, but as in Chekhov’s time, there is no bridge that links the island with the mainland.

Today regular ferry services operate from Vanino in the Khabarovsk region and Kholmsk in southern Sakhalin. Islanders often complain that the ferry is a popular route for criminals from other parts of Russia and former Soviet republics to come to the now oil-rich island.

When Chekhov took the ferry across the “cold and colorless roaring sea” to get to a northern Sakhalin port, it was actually used to transport those who were considered the worst of criminals.

The way these convicts were treated saddened the great writer. “On the Amur steamer going to Sakhalin, there was a convict who had murdered his wife and wore fetters on his legs,” Chekhov wrote in his book Sakhalin Island. “His daughter, a little girl of six, was with him. I noticed wherever the convict moved the little girl scrambled after him, holding on to his fetters. At night the child slept with the convicts and soldiers all in a heap together.”

When Chekhov arrived on the island, he witnessed the brutality of its inhospitable climate and the utter lack of facilities for the prisoners. He considered the island a frozen “hell.”

The city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk did not exist in its present form when the writer visited it, as the Japanese occupied the area after the Russo-Japan War of 1905 and almost changed it completely. But Chekhov wrote about the settlement of Vladimirovka, which is now in the periphery of the island’s largest city and administrative centre.

The settlement had 46 houses and 91 inhabitants in 1890 and was a linear-shaped colony. Among its residents were Polish deportees. Names such as Kovalsky, Kriminetsky and Krakowsky are still common on the island.

In 2013, Vladimirovka has a collection of small dachas and a few larger wooden independent houses. Immigrants from places as far away as Armenia and Kyrgyzstan stay in the smaller houses and renting a flat for these blue-collared workers, who survive on odd jobs, is next to impossible.

Long-term Russian residents also complain about the poor infrastructure in a place that is just a few kilometres away from the modern glass and steel buildings of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk that house international oil companies. The common complaints heard on the streets of Vladimirovka are the irregular water supply and the lack of safety at night.

The area is also oddly called Shanghai, since many of the poorer Koreans, who were left behind on the island, when the Japanese were evicted in 1945, stayed in Vladimirovka. The idea behind the name, say local historians, is that this was looked on as an Asian area. Visitors from the real Shanghai would undoubtedly be shocked that such an area, even if unofficially, shares a name with their great city.

Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky

Most of Chekhov’s time in Sakhalin was spent in the small town of Alexandrovsk-Sakhalinsky, a quiet port in the northwestern part of the island. It was here that the conditions of life horrified the writer. In fact, the last section of the short story ‘The Murder’ is set on a Sakhalin Island prison, and Alexandrovsk is believed to be the setting, since it housed the largest of the island’s prisons.

Alexandrovsk was the administrative

There still a few traces of 1890 in the town, although thankfully the penal colony was shut down a very long time ago. Chekhov would have seen the former treasury building, a wooden log house built ten years before he arrived on the island. It is believed to be the oldest surviving man-made structure on the island.

The house where the writer lived still stands and is now a small museum with items from the period when Chekhov was on his mission.

From penal entrenchment to voluntary migration

Although Chekhov would have certified the island as the worst place he had ever seen, on account of the untold human suffering that he witnessed there, the 20th and 21stcenturies brought a lot of changes to Sakhalin. The Japanese occupiers rapidly developed the southern part of the island and post-1945, many highly-skilled specialists were encouraged by the Soviet authorities with good salaries and accommodation to come and settle down on the island.

The decision to actively explore the vast oil and gas reserves on the island’s shelf in the early 2000s not only brought foreign specialists

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox