Source: Anton Churochkin

In the mid-2000s, the Russian State Library (RSL) launched the National Electronic Library project with the aim of digitizing books published before 1831.

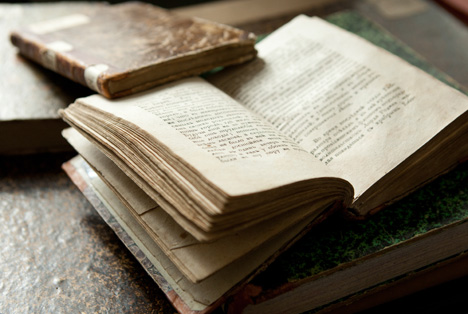

Many important texts have already been scanned; from the hand-written Archangel Gospel of 1092 – the fourth oldest known East Slavonic manuscript – to the Octoechos, a book of Orthodox Church psalms printed in 1491 in Krakow. It is one of the first books to use Cyrillic script and is worth several million dollars – although, of course, it belongs to the state and will not be sold. “These books only used to be released by special permission – and only then to prominent scholars,” explains Tatyana Garkushova from the library’s scanning department as she flicks between priceless ancient manuscripts on her computer screen. Now they are available to everyone at the RSL Digital Library page.

Digitizing the past

“The Russian State Library’s collection of rare books has some 300,000 items in it. As of now, around 9,000 of them have been digitized,” Tatyana continues. The National Electronic Library project, which now unites libraries from all over the country, has recently received the support of the Russian Ministry of Culture.

For centuries taking good care of the paper copies of the texts was the only option available to the archivists. However, with the advent of the digital age – still a mere 30 years old – new opportunities are opening up. “Books are digitized in order to make them accessible to all,” says Roman Kurbatov, the head of the scanning department. “Also, there are other factors to consider as well. In the 19th century, people wrote with zinc-based ink, which eventually starts ‘eating through’ the sheets of paper and coming out the other side. Over time, this makes the text incomprehensible on both sides of the paper.”

“Interestingly, the oldest and most expensive books are the best preserved,” Roman continues. “They were treated with great care from the very beginning: stored in special conditions, rarely opened. We have come across a contemporary French edition of Rabelais dating from about the 1530s. It is in no worse condition than mid-19th-century books.”

The process of scanning must be done carefully so that the scanner doesn’t damage the original books. A book is placed into a special ‘cradle,’ on a soft pad that can be adjusted to the form and width of its binding. There are scanners to fit all formats, from miniature books to A0 size (33.1 × 46.8 inches). They use special lighting that doesn’t damage the ink and paper.

Space technology for Da Vinci

The RSL collection features numerous copies of large and unconventional formats: gift books, large-scale atlases, graphic sheets. To digitize them, the library set up a Metis Systems scanner, which can fit originals up to 20 inches thick and weighing up to 110 pounds. This scanner was recently used to digitize the Atlantic Codex, a 1,119-page manuscript by Leonardo Da Vinci. The engineers who made that scanner previously worked at the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The RSL website is making digital versions of its books available via a web browser or as downloads in .pdf or iPad-compatible format. There are some real treasures in its digital collection, including Paul I’s personal pocket calendar, a mid-17th century Gospel, 16th century books from Francysk Skaryna’s printing house in Prague. The scans are of such good quality that it is possible to see every minute detail of the originals, including etchings and bookplates – small decorative labels used to show the book’s owner.

Scans, of course, cannot give you the feel of holding a real book. “When we were scanning the famous Schneerson library, we found various interesting objects used as bookmarks: goose quills, hairs, necklaces, money, personal notes,” Roman recalls.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox