Aces of 586 the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment (L-R): Lilya Litvyak, Katya Budanova, Masha Kuznetsova near the Yak-1 fighter. Source: RIA Novosti

On the first page of Lyuba Vinogradova’s fine book about Soviet women pilots, she compares Hitler’s attempted invasion of Moscow in 1941 to Napoleon’s in 1812. Vinogradova centers her comparison on the neo-gothic Petrovsky Palace, built on the road to St. Petersburg in the late 18th-century as a rest house for traveling royalty. Napoleon sheltered here as Moscow burned and the palace later became an aeronautical academy, whose alumni included cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. By World War II, when Vinogradova takes up the tale, the palace’s rooms are noisy with “a more motley assembly than they had ever witnessed,” directed by women in uniform.

Vinogradova’s skill as a writer is to see both the larger, historical picture and the vivid, individual detail. In the introduction of the book, she writes of her fascination with “stories about peoples’ experiences.”

Born in Moscow, Vinogradova describes herself as “not an historian,” but she has worked in many Russian archives. She helped research Antony Beevor’s skillful patchwork of human stories in Stalingrad and many other books. She collaborated with Beevor again on the translation and editing of Vasily Grossman’s diaries in A Writer at War.

|

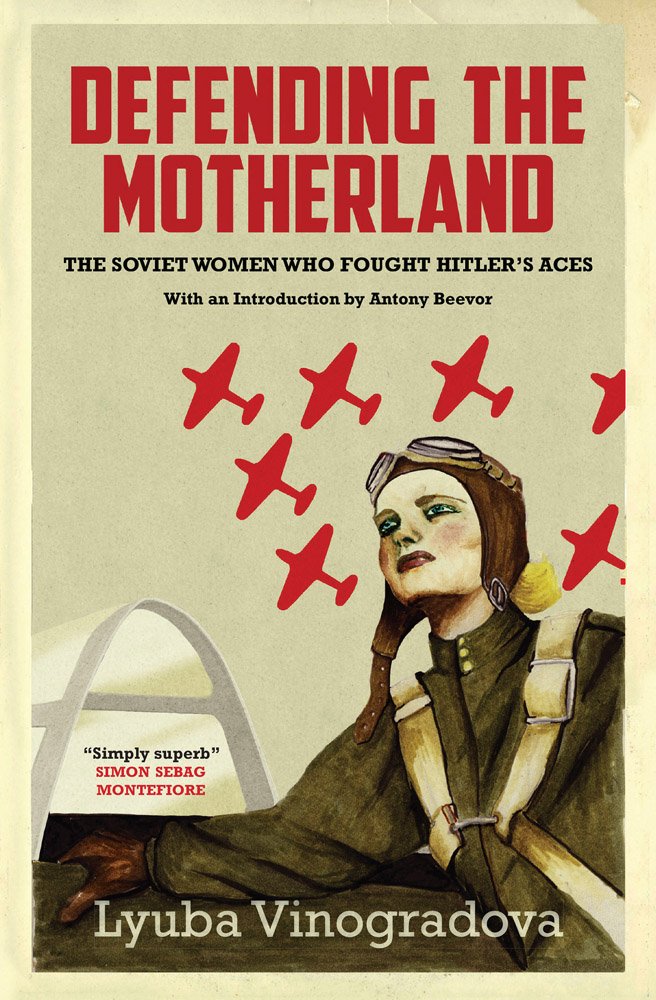

Lyuba Vinogradova - Defending the Motherland: The Soviet Women who Fought Hitler’s Aces (Maclehose Press, April 2015) |

Introducing Vinogradova’s new book, Beevor calls her theme “a unique phenomenon in the history of modern conflict”, which also tells us a great deal “about Soviet society under Stalin.”

Arch Tait, who translated Vinogradova’s book from Russian, has captured her slightly breathless style as she details the lives of these diverse and courageous women, from penniless poultry farmers to budding astronomers.

The female pilot corps consisted of three units, one of which was the feared “Night Witches.”

But Vinogranova’s book is not a simple tale of idealism, heroism and survival. Marina Raskova, whose record-breaking adventures as an aviatrix inspired “millions of Soviet women,” is soon revealed as a secret officer of the NKVD, the KGB’s murderous precursor.

Legendary pilot Valentina Grizodubova later said bitterly of Raskova: “I have no doubt that people suffered because of her.” Vinogradova’s awareness of context and complexity show how one generation’s idols can become uneasy ghosts. In the cold, retrospective light of history the image of young Raskova, dressed in military white, skywriting “Glory to Stalin!” at the annual Soviet air show Tushino Aviation Day, is more chilling than heart-warming.

There is plenty of real heroism in “Defending the Motherand,” which includes first person accounts from survivors. The Night Witches switched off their engines to glide silently, but hitting an unexpected snowstorm in March 1942 was like “flying though milk;” four women died in the disorientating whiteness, where “lights on the ground … began to seem like distant stars.”

Lilya Litvyak, the “White Lily of Stalingrad” was the first woman who came to Vinogradova’s attention and her story forms a narrative thread throughout the book. A beautiful, formidable fighter pilot, she was killed in her early twenties, a death both emblematic and poignant. Her sudden disappearance led to conflicting rumors: that she was captured alive or that she had crashed, leaving only scraps of parachute-silk underwear and bleached blonde hair. In her last letter to her mother she wrote: “I have a burning desire to drive those German reptiles out of our land…”

During World War II, nearly a million women served in the Soviet forces and Vinogradova, whose next book will cover female Red Army snipers, has unearthed a rich seam of historical detail in charting their relatively unknown stories.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox