|

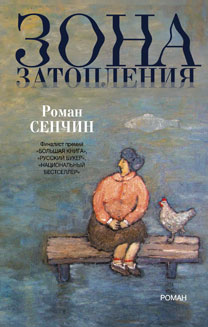

| 'Flood area' by Roman Senchin (released in Russian March 16, 2015), Elena Shubina Publishing House |

The sun slowly descends towards the taiga until, on touching the tops of larch trees, it immediately begins to dim and fade from view. Dusk sets in half an hour later and the diesel generators are put to full blast. The next three hours are the best time of day for the village, which becomes very cozy. You can watch TV or mend your underwear by lamplight – or your winter clothes, which will soon become so indispensable.

There was a time when the whole village had power 24 hours a day. There was even talk that it would be connected up to the Ust-Ilim hydroelectric plant, but that was later ruled unprofitable. In addition, construction was approved for another hydroelectric plant further down river that will submerge Pylevo under its water reservoir. The power outages began after that.

Things get particularly tough in November and December, when there is hardly any daylight at all; the sun only creeps slightly above the horizon and sinks at four in the afternoon. Darkness fills the cottages too. It feels as if you are at the bottom of a pit or in a lair. The situation improved a touch in the late 1990s, and though you couldn’t switch on the TV when you wanted, at least you were guaranteed to have some light inside your home in the evening.

It is nice to spend those last few hours before nightfall outdoors. It is cool outside, but not cold, and it makes you want to sit on a bench or a porch and talk with a dear, long-time friend, to think, to reminisce. The sounds and smells become more acute at dusk. The short grass in the yard has a slightly pungent yet pleasant scent and you can hear the sound of the nearby sandbank. The muggy smell of the cattle-pen is wafting over; the milked cows are sighing, the pigs are nuzzling the walls of their enclosure, the hens are settling onto their perches, bickering and then calming each other down with their soft clucking.

Natalya Sergeyevna’s house is packed with people, but they are all trying not to make any noise; they are speaking in half-whispers and picking up objects with extra care, gingerly, as if they are doing it without the host’s permission.

The majority of the visitors are either sitting or standing in the kitchen, discussing tomorrow’s funeral and trying to resolve outstanding issues. For example, how to transport the coffin to the cemetery. All the remaining trucks are broken, but using a cart would be too embarrassing. After all, it is not the 19th century anymore. The available options are either to carry the coffin, with several people taking turns (the journey is not far but it is mostly uphill), or to take it in the Toyota.

The Toyota belongs to Dmitri Arkadyevich Privalikhin, a cousin once removed of Natalya Sergeyevna’s husband and the father of a successful businessman, Oleg, whose nickname has been Alligator since childhood – partially because it sounds a bit like “Oleg”, but perhaps mainly because of his bulldog determination in everything he tackles. Oleg moved to Krasnoyarsk in the 1990s, made a fortune in trade and presented his father with the 4x4. And now Dmitri Arkadyevich has offered to take his elderly female relative to the cemetery.

“I’ll lift up back door, secure it, and we’ll put the coffin into the trunk,” he says.

“Into the trunk,” smirks an old man by the name of Merzlyakov.

“This is a proper trunk, not like in a Lada! If I take down the back seat, it’ll give you six-and-a-half feet of space!”

“Quiet!” says Valentina Loginova, hushing Privalikhin in alarm. She is the youngest woman present, although she is also on the cusp of old age.

“It’s a big car,” pipes up Zhenka Glukhikh. He came here straight from the cemetery and has already had two small shots of vodka. “It looks like a hearse as it is.”

“The most important thing is that it can go to places that all-terrain vehicles can’t always manage.”

In walks Ulyana Pavlovna Ignatova. She is tilting to the left with each step, as if her left side is heavier than the right.

Ulyana Pavlovna comes from a family of exiles. There used to be many of them in the village and the nearby area, but some left as soon as they could, while others have died. All that now remains of them are surnames passed down to children and grandchildren - Krikau, Sneider, Gafner, Ekkert, Shroo, Kaikher – and crosses from non-Orthodox traditions on their graves. Ulyana Pavlovna is the last exile in Pylevo who remembers another land, far away, which she was forced to leave and come here.

She was born somewhere in Lithuania or Latvia; she does not like speaking about her past, but the locals know that her family was exiled to Siberia after the war for links to either the Germans or to the Forest Brothers. They settled in Bolshakov, a village nearby, on the river, some 45 miles away. Several years later Ulyana married Ignatov, who brought her here – to Pylevo. She has lived here since, giving birth to five children.

In the 1980s, she was visited by several young people from her birthplace. The conversation was difficult and ended with her husband Ignatov yelling, as he was pushing the visitors out of the gate, “She is not returning anywhere! Her home is here!”

They left. Ignatov died three years later. By then their children had already left home, and Ulyana Pavlovna was left all by herself. She was growing old and decrepit. She was no different from the local people; perhaps only her voice was different. Not her words, but her voice, which had an alien timbre. Older villagers say that it was a joy to listen to her when she was younger – it was like the cooing of a dove. Even now her voice stands out, and villagers only have to hear her to smile and recognize who it is.

***

Roman Senchin was born in the Republic of Tyva in Siberia in 1971. He moved to Moscow in the 1990s and is now deputy editor-in-chief of the Literaturnaya Gazeta cultural newspaper. One of his best-known novels, “Eltyshevy”, is written in a genre known as rural prose, with nondescript losers for main characters. The critic Lev Danilkin sums it up in this way: “‘Eltyshevy’ is ‘Robinson Crusoe’ the other way round: a clear degradation of the human spirit, losing out to the outside world in every department.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox