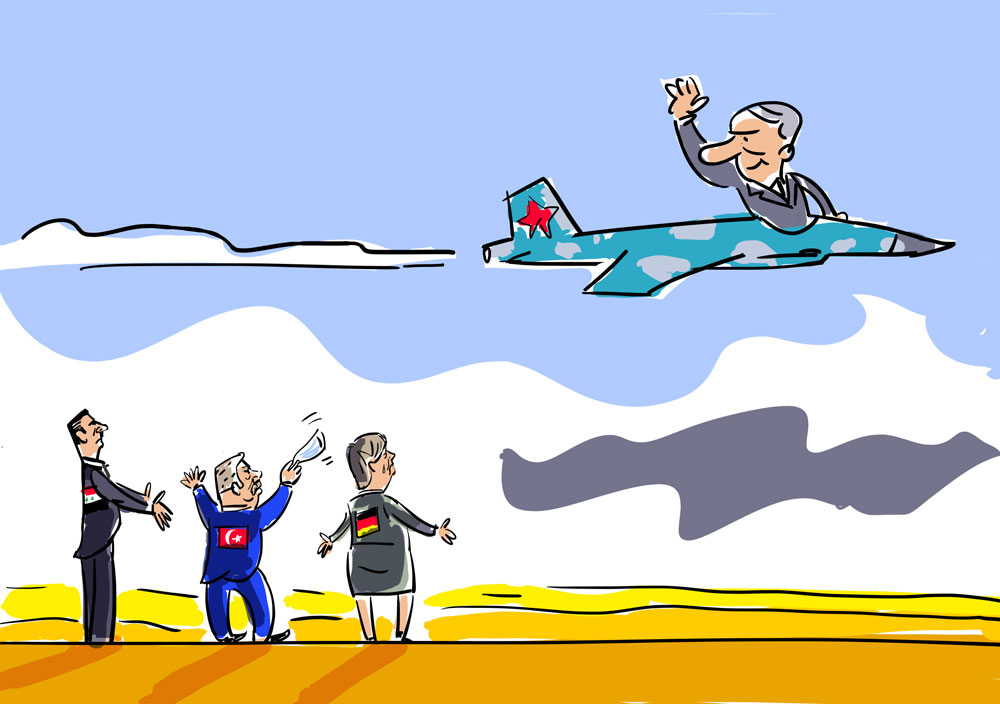

Drawing by Iorsh

The decision to pull Russian forces out of Syria has not only surprised the West but has engendered a significant number of conspiracy theories about the reasons behind it.

However, there was really nothing to be surprised about. Russian President Vladimir Putin goes to the end only when it concerns Russia's security or his plausibility as a leader. If such critical interests are not at stake, the Russian president rather easily "leaves the process."

Moreover, he always "strikes first," something he has admitted on several occasions, but he always "leaves the battle first" also, if it can be done elegantly and without loses. This is the fundamental principle of the Russian "political judo” that has been practiced for many years now.

In a certain way the West, evaluating the consequences of Russia's operation in Syria, has fallen into its own trap of distrust of Moscow.

From the very beginning the Kremlin had emphasized the limited nature of the Russian air force mission and the unwillingness to get involved in a ground operation.

But the West continued to suspect Moscow of having some kind of hidden agenda.

Moscow had said that the operation would continue as long as the Syrian army was fighting the terrorists. However, when Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad's army began pretending to be besieging Palmyra but in reality concentrating its forces in the areas around Aleppo, Russia decided to end the operation.

Moscow clearly demonstrated to Assad that it supports his fight against ISIS and other terrorist organizations but not his attempts to use Russian military potential to solve the problems of his political survival.

Of course, Moscow's decision to wrap up the operation has a "false bottom." But this is also, as strange as this sounds, rather "transparent."

In part, the Kremlin's decision is related to the growth of Russian-Iranian disagreements on a wide range of issues, including cooperation in the oil sector. But Moscow never hid the fact that it wants to act in Syria as a component of a large anti-terrorist coalition and considers it a part of a "big picture."

The moment Iran stopped being as cooperative as before and revealed its unwillingness to actively work in Syria (the departure of Hezbollah units from Syria began before Putin announced his decision), one of the most important conditions for Russia continuing its operations simply disappeared. Instead there appeared risks that the Kremlin justly preferred to remove at their earliest stage of development.

Obviously the current Iranian administration is determined to use the lifting of the sanctions to the maximum, demonstrating the country's capability to be a regional leader.

What is more obvious is Moscow's determination to shatter German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's propaganda tying Europe's migration problem to Russia's actions in Syria.

The Kremlin's maneuver has rendered ineffectual this propaganda campaign, a campaign that indeed irritated Vladimir Putin, especially since the flow of refugees is unlikely to recede. Considering the two-year political confrontation with Europe and the continuous renewal of the sanctions against Russia, the determination to use the European politicians' miscalculations is completely logical.

The limited pragmatism and a certain cynicism in contemporary Russian politics are directly contrary to the West's ideological and propagandistic messianism. And in its limited pragmatism today's Kremlin, as strange as it seems, is frank and limitedly open to interaction.

We should also not lose sight of the following: The Kremlin has usually been extremely sensitive to the fluctuations of public opinion, all the more in periods of economic difficulties that are also related to its foreign policy. Even though the operation in Syria had the support of Russian public opinion, which viewed it as yet another expression of the new foreign policy status, the possibility of a direct military clash in Syria with Turkey, and consequently, the U.S., raised a logical concern both among the expert community and the relatively broad layers of public opinion.

It can be argued how realistic it was and how far Erdogan would have gone in his determination to preserve the "geopolitical" conquests he had made in the last years. But in Russia's public opinion such a possibility was considered entirely real. This showed the Kremlin the limits of a permissible escalation. Since the operation's military aims and the political objective to re-establish relations with Washington were already decided and announced, the Kremlin as usual did not want to take risks and create an unnecessary political tension in public opinion.

Now, after Russia's departure from the field of realpolitik in Syria, the West, and first and foremost the U.S., is faced with new challenges: will Washington be able to independently manage the built-up situation and demonstrate decisiveness in practical politics?

The U.S. has been left alone with the region's political and military problems, and not only with Assad, but also with Erdogan, who is becoming more and more uncontrollable, with the Islamists, who have preserved their military and political potential, and with the Saudis, who are getting more and more involved in the internal crisis.

Putin will be available to give Obama a hand if he needs it.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox