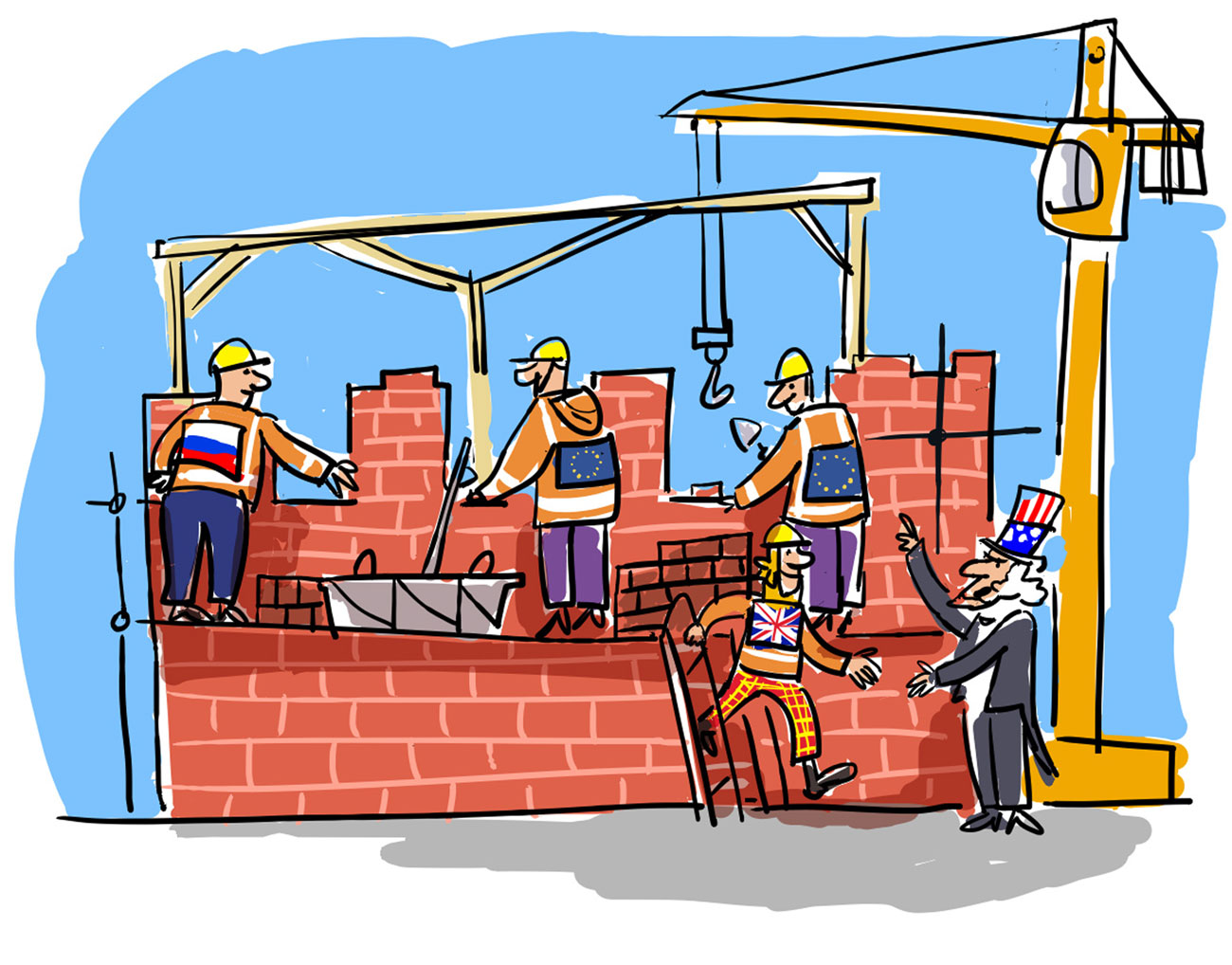

Drawing by Alexei Iorsch

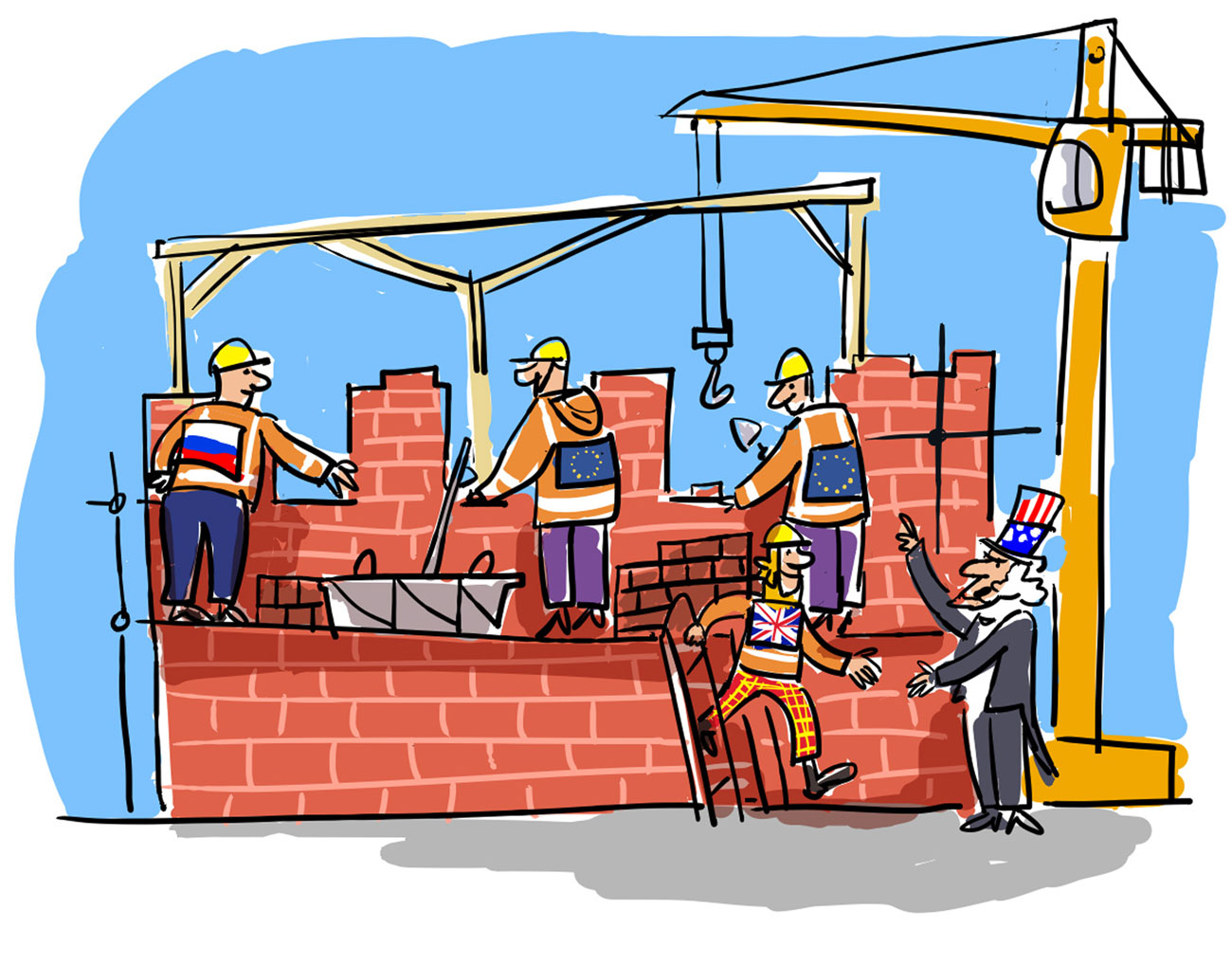

Drawing by Alexei Iorsch

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Britain’s impending exit from the European Union may not have any long-term positive implications for Russia. The key question that everyone is asking themselves today is whether any side will be better off after Britain’s vote to leave the EU. Britain will soon be starting a painful “divorce” from continental Europe, with uncertain implications.

A fairly popular answer voiced by former Prime Minister David Cameron and former U.S. ambassador to Moscow Michael McFaul, among others, is that the only ones to gain will be Russia and its president Vladimir Putin.

I genuinely complement Putin for his victory tonight on Brexit, but Russians scream defensively, "Putin is not guilty'. What does that mean?

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) June 24, 2016

The argument, which has been widely accepted, was that a split in Europe and a revival of the demons of European nationalism was in Putin’s interests. It was said that post-Brexit, the Europeans would have even less potency to resist Russia and maintain the sanctions policy.

Hardly anyone in the West trusts Putin when he asserts that a strong Europe is a better option for Russia. Yet Putin is quite sincere in that matter. However, his idea of what constitutes a “strong Europe” differs radically from the accepted notion.

In fact, Europe’s leaders do not impress the Russian president as strong, independent statesmen and women. From his perspective, it is difficult to find common ground with them, because they act with an eye to Brussels and Washington when faced with a challenge.

If, on the other hand, the heads of France, Italy, Poland, Greece and other countries that Russia is dealing with had true sovereignty, then the Kremlin chief believes it would be easier to come to an understanding with them, settle all controversial problems, and establish mutually beneficial relations.

Putin’s ideal of a Europe consisting of completely sovereign states with independent leaders at the head has an understandable origin from a psychological point of view. At the beginning of the 21st century, Putin, who was then just a young, inexperienced statesman, found a favorable reception from the ring of world leaders and managed to establish friendly relations with America’s George W Bush, France’s Jacques Chirac, Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi and Germany’s Gerhard Schröder. He never accused them of weakness or lack of independence.

However, the leaders of these democratic nations have since been replaced while Putin has remained at the helm in Russia. By the middle of the second decade of the century, German Chancellor Angela Merkel remains the only one who matches – with serious reservations –Putin’s ideal of the leader of a sovereign state. The rest of them Putin tends to look down on, which does not help establish friendship and mutual understanding.

The EU referendum and the prospect of a growing isolation of European states hardly herald the beginning of an epoch of strong leaders. More likely is the opposite: For years if not decades to come, Britain and other countries are doomed to an exhausting struggle among various political groups, backing or opposing integration. In such a Europe, Putin will not be able to find any independent political leaders.Moreover, it is clearly not Russia that the weak European leaders will be turning to for support. With Britain lost, continental Europe will not be less pro-American, as some Russian politicians believe, for the reason that under such conditions, Washington will become the main external guarantor of the idea of a united Europe while keeping special relations. As for the Euroskeptics, their love for Russia and the Kremlin’s strongman will only last until they come to power. If that happens, Russia for the “independent, sovereign leaders of Europe” will automatically turn into a political rival that is only fit to be used temporarily, as a bogeyman for opponents.

If history provides any lessons for us to learn, it is that a Europe split into national states inevitably plunges into a void of wars and conflicts. Such a scenario hardly has any gains in store for Russia.

In Russia, the popular opinion is that without the UK, the EU will not be able to maintain for long the policy of sanctions on Russia, and therefore the results of the British referendum must be welcomed. This may be true, but it is possible that, contrary to expectations, the European Union will become more consolidated, and U.S. influence on European politics may grow instead.

Most importantly, by putting the repeal of sanctions at the centre of its foreign policy and assessing all the developments in the world in terms of whether they are for or against sanctions, Russia drives itself into a strategic impasse.

It may seem that crises and catastrophes are good for Russia, as thanks to them, the sanctions may be forgotten and dwindle quietly. But is Russia indifferent to what kind of world it will face in the “post-sanctions” era? Will it suit Russia if that world is just a heap of smoking ruins? One should believe that it would not.Brexit can be compared in many ways to another sensational event of recent years, the incorporation of Crimea into Russia. Both events were mainly driven by the idea of resistance to external influence: Russia feared the appearance of NATO bases in Sevastopol while British voters opposed the omnipotence of Brussels bureaucrats.

Seriously challenged by both events, the established system of international relations has been put into motion. Both Russia and Britain have shown, each in their own way, that it is impossible for them to maintain the status quo, which they regard as inconsistent with their national interests.

Even though the referendum can be considered as a triumph of democracy and rule of law while the “polite people” appeared in Crimea as a result of a carefully planned covert operation that raises a lot of legal questions, it is hard to deny that in both cases, it was a manifestation of revanchism after decades of progressive development.

Ivan Tsvetkov is associate professor of American Studies, International Relations Department, St. Petersburg State University.

This opinion was first published by Russia Direct.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox