An Indian Army soldiers at Pakistani positions in a village across an open field, 1,500 yards inside the East Pakistan border at Dongarpara on Dec. 7, 1971.

APWashington DC, December 3, 1971, 10:45am.

U.S. President Richard Nixon is on the phone with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, hours after Pakistan launched simultaneous attacks on six Indian airfields, a reckless act that prompted India to declare war.

Nixon: So West Pakistan is giving trouble there.

Kissinger: If they lose half of their country without fighting they will be destroyed. They may also be destroyed this way, but they will go down fighting.

Nixon: The Pakistan thing makes your heart sick. For them to be done so by the Indians and after we have warned the b**** (reference to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi). Tell them that when India talks about West Pakistan attacking them it's like Russia claiming to be attacked by Finland.

President Richard Nixon and India's Prime Minister Indira Gandhi talk at the White House, November 1971

Getty ImagesWashington, December 10, 1971, 10:51am.

A week later, the war is not going very well for Pakistan, as Indian forces push through East Pakistan and the Pakistan Air Force sees heavy losses. Meanwhile, the Pakistani military in the west is demoralised and on the verge of collapse, as the Indian Army and Air Force attack round the clock.

Nixon: Our desire is to save West Pakistan. That's all.

Kissinger: That's right. That is exactly right.

Nixon: All right. Keep those carriers moving now.

Kissinger: The carriers—everything is moving. Four Jordanian planes have already moved to Pakistan, 22 more are coming. We're talking to the Saudis, the Turks we've now found are willing to give five. So we're going to keep that moving until there's a settlement.

Nixon: Could you tell the Chinese it would be very helpful if they could move some forces or threaten to move some forces?

Kissinger: Absolutely.

Nixon: They've got to threaten or they've got to move, one of the two. You know what I mean?

Kissinger: Yeah.

Nixon: How about getting the French to sell some planes to the Paks?

Kissinger: Yeah. They're already doing it.

Nixon: This should have been done long ago. The Chinese have not warned the Indians.

Kissinger: Oh, yeah.

Nixon: All they've got to do is move something. Move a division. You know, move some trucks. Fly some planes. You know, some symbolic act. We're not doing a goddamn thing, Henry, you know that.

Kissinger: Yeah.

Nixon: But these Indians are cowards. Right?

Kissinger: Right. But with Russian backing. You see, the Russians have sent notes to Iran, Turkey, to a lot of countries threatening them. The Russians have played a miserable game.

If the two American leaders were calling Indians cowards, a few months earlier the Indians were a different breed altogether. This phone call is from May 1971.

Nixon: The Indians need—what they need really is a—

Kissinger: They’re such bastards.

Nixon: A mass famine. But they aren't going to get that…But if they're not going to have a famine the last thing they need is another war. Let the goddamn Indians fight a war.

Kissinger: They are the most aggressive goddamn people around there.

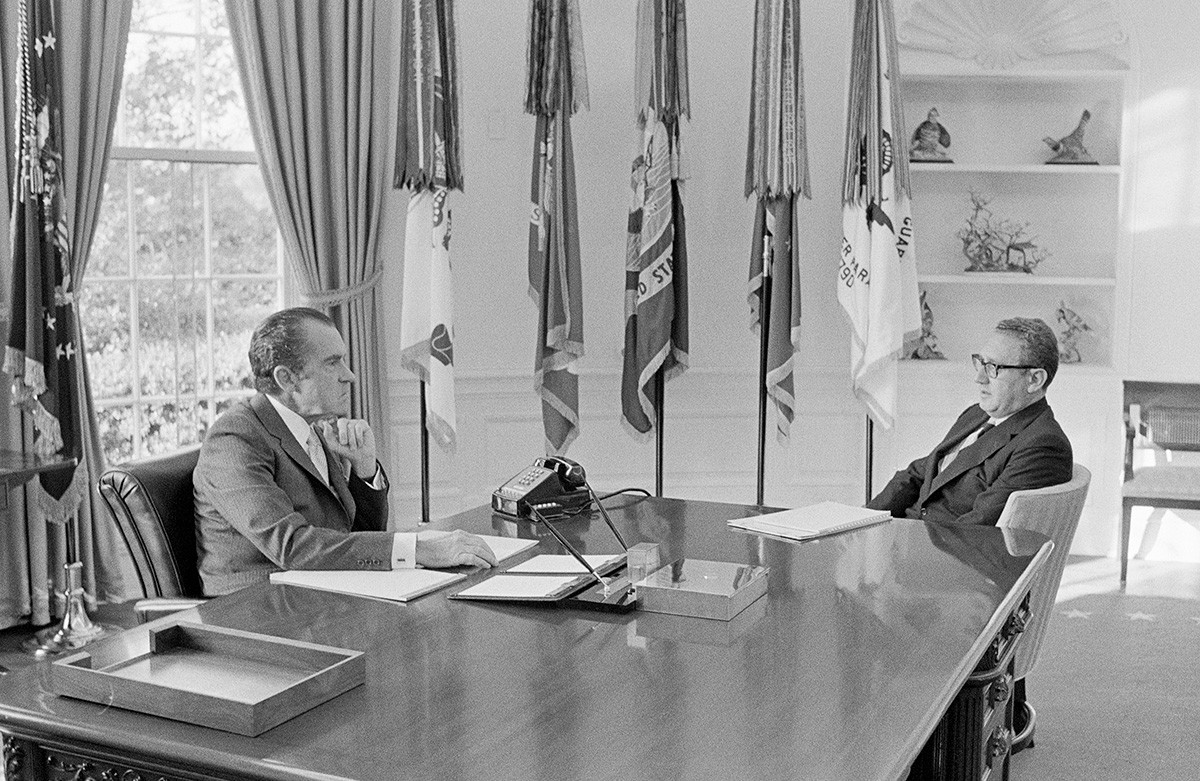

President Richard Nixon meets with National Security Affairs Advisor Henry Kissinger in the Oval Office, 1971

Getty ImagesThe 1971 war is considered to be modern India’s finest hour, in military terms. The quick reaction of the Indian army, navy and air force; a brass led by the legendary Sam Maneckshaw; and ceaseless international lobbying by the political leadership worked well to set up the victory. After two weeks of vicious land, air and sea battles, nearly 100,000 Pakistani soldiers surrendered to India’s army, the largest such capitulation since General Paulus’ surrender at Stalingrad in 1943. However, it could all have come unstuck without help from veto-wielding Moscow, with which New Delhi had the foresight to sign a security treaty in 1970.

As Nixon’s conversations with the wily Kissinger show, the forces arrayed against India were formidable. The Pakistani military was being bolstered by aircraft from Jordan, Iran, Turkey and France. Moral and military support was amply provided by the U.S., China and the UK. Though not mentioned in the conversations, the UAE sent in half a squadron of fighter aircraft and the Indonesians dispatched at least one naval vessel to fight alongside the Pakistani Navy.

However, Russia’s entry thwarted a scenario that could have led to multiple pincer movements against India.

On December 10, even as Nixon and Kissinger were frothing at the mouth, Indian intelligence intercepted an American message, indicating that the U.S. Seventh Fleet was steaming into the war zone. The Seventh Fleet, which was then stationed in the Gulf of Tonkin, was led by the 75,000 ton nuclear powered aircraft carrier, the USS Enterprise. The world’s largest warship, it carried more than 70 fighters and bombers. The Seventh Fleet also included the guided missile cruiser USS King, guided missile destroyers USS Decatur, Parsons and Tartar Sam, and the large amphibious assault ship USS Tripoli.

Standing between the Indian cities and the American ships was the Indian Navy’s Eastern Fleet led by the 20,000-ton aircraft carrier, Vikrant, with barely 20 light fighter aircraft. When asked if India’s Eastern Fleet would take on the Seventh Fleet, the Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Vice Admiral N. Krishnan, said: “Just give us the orders.” The Indian Air Force, having largely dealt with the Pakistani Air Force within the first week of the war, was reported to be on alert for any possible intervention by aircraft from the Enterprise.

Meanwhile, Soviet intelligence reported that a British naval group led by the aircraft carrier Eagle had moved closer to India’s territorial waters. However, India did not panic. It quietly sent Moscow a request to activate a secret provision of the Indo-Soviet security treaty, under which Russia was bound to defend India in case of any external aggression.

The British and the Americans had planned a coordinated pincer to intimidate India: while the British ships in the Arabian Sea would target India’s western coast, the Americans would make a dash into the Bay of Bengal in the east where 100,000 Pakistani troops were caught between the advancing Indian troops and the sea.

.jpg)

An Indian Army machine gunner fires at Pakistani positions in a village across an open field, 1,500 yards inside the East Pakistan border at Dongarpada on Dec. 7, 1971

APTo counter this two-pronged British-American threat, Russia dispatched a nuclear-armed flotilla from Vladivostok on December 13 under the overall command of Admiral Vladimir Kruglyakov, the Commander of the 10th Operative Battle Group (Pacific Fleet). Though the Russian fleet comprised a good number of nuclear-armed ships and atomic submarines, their missiles were of limited range (less than 300 km). Hence, to effectively counter the British and American fleets the Russian commanders had to undertake the risk of encircling them to bring them within their target. This they did with military precision.

In an interview to a Russian TV program after his retirement, Admiral Kruglyakov, who commanded the Pacific Fleet from 1970 to 1975, recalled that Moscow ordered the Russian ships to prevent the Americans and British from getting closer to “Indian military objects”. The genial Kruglyakov added: “The Chief Commander’s order was that our submarines should surface when the Americans appear. It was done to demonstrate to them that we had nuclear submarines in the Indian Ocean. So when our subs surfaced, they recognised us. In the way of the American Navy stood the Soviet cruisers, destroyers and atomic submarines equipped with anti-ship missiles. We encircled them and trained our missiles at the Enterprise. We blocked them and did not allow them to close in on Karachi, Chittagong or Dhaka."

At this point, the Russians intercepted a communication from the commander of the British carrier battle group, Admiral Dimon Gordon, to the Seventh Fleet commander: “Sir, we are too late. There are the Russian atomic submarines here, and a big collection of battleships.” The British ships fled towards Madagascar while the larger U.S. task force stopped before entering the Bay of Bengal.

The Russian manoeuvres clearly helped prevent a direct clash between India and the U.S.-UK combine. Newly declassified documents reveal that the Indian Prime Minister went ahead with her plan to liberate Bangladesh, despite inputs that the Americans had kept three battalions of Marines on standby to deter India and that the American aircraft carrier USS Enterprise had orders to target the Indian Army, which had broken through the Pakistani Army’s defences and was heading to the gates of Lahore, West Pakistan’s second largest city.

According to a six-page note prepared by India's foreign ministry, "The bomber force aboard the Enterprise had the U.S. President's authority to undertake bombing of the Indian Army's communications, if necessary."

Despite Kissinger’s goading and desperate Pakistani calls for help, the Chinese did nothing. U.S. diplomatic documents reveal that Indira Gandhi knew the Soviets had factored in the possibility of Chinese intervention. According to a cable referring to an Indian cabinet meeting held on December 10, “If the Chinese were to become directly involved in the conflict, Indira Gandhi said, the Chinese know that the Soviet Union would act in the Sinkiang region. Soviet air support may be made available to India at that time.”

Interestingly, while the cable is declassified, the source and extensive details of the Indian Prime Minister’s briefing remain classified. “He is a reliable source” is all that the document says. There was very clearly a cabinet level mole the Americans were getting their information from.

Leonid Brezhnev

SputnikOn December 14, General A.A.K. Niazi, Pakistan's military commander in East Pakistan, told the American consul-general in Dhaka that he was willing to surrender. The message was relayed to Washington, but it took the U.S. 19 hours to relay it to New Delhi. Files suggest senior Indian diplomats suspected the delay was because Washington was possibly contemplating military action against India.

Kissinger went so far as to call the crisis “our Rhineland” a reference to Hitler’s militarisation of German Rhineland at the outset of World War II. This kind of powerful imagery indicates how strongly Kissinger and Nixon came to see Indians as a threat.

An Indiana University study of the conflict says: “The violation of human rights on a massive scale—described in a March 30 U.S. cable as “selective genocide”—and the complete disregard for democracy were irrelevant to Nixon and Kissinger. In fact, the non-democratic aspects of Pakistani dictator Yahya Khan’s behavior seemed to be what impressed them the most. As evidence mounted of military atrocities in East Pakistan, Nixon and Kissinger remained unmoved. In a Senior Review Group meeting, Kissinger commented at news of significant casualties at a university that, ‘The British didn’t dominate 400 million Indians all those years by being gentle’.”

Nixon and Kissinger phoned Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev and asked for guarantees that India would not attack West Pakistan. “Nixon was ready to link the future summit in Moscow to Soviet behavior on this issue," writes professor Vladislav M. Zubok in A Failed Empire. "The Soviets could not see why the White House supported Pakistan, who they believed had started the war against India. Brezhnev, puzzled at first, was soon enraged. In his narrow circle, he even suggested giving India the secret of the atomic bomb. His advisers did their best to kill this idea. Several years later, Brezhnev still reacted angrily and spoke spitefully about American behavior."

Another telephone conversation between the scheming duo reveals a lot about the mindset of those at the highest echelons of American decision making:

Kissinger: And the point you made yesterday, we have to continue to squeeze the Indians even when this thing is settled.

Nixon: We've got to for rehabilitation. I mean, Jesus Christ, they've bombed—I want all the war damage; I want to help Pakistan on the war damage in Karachi and other areas, see?

Kissinger: Yeah

Nixon: I don't want the Indians to be happy. I want a public relations programme developed to piss on the Indians.

Kissinger: Yeah.

Nixon: I want to piss on them for their responsibility. Get a white paper out. Put down, White paper. White paper. Understand that?

Kissinger: Oh, yeah.

Nixon: I don't mean for just your reading. But a white paper on this.

Kissinger: No, no. I know.

Nixon: I want the Indians blamed for this, you know what I mean? We can't let these goddamn, sanctimonious Indians get away with this. They've pissed on us on Vietnam for 5 years, Henry.

Kissinger: Yeah.

Nixon: Aren't the Indians killing a lot of these people?

Kissinger: Well, we don't know the facts yet. But I'm sure they're not as stupid as the West Pakistanis—they don't let the press in. The idiot Paks have the press all over their place.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox