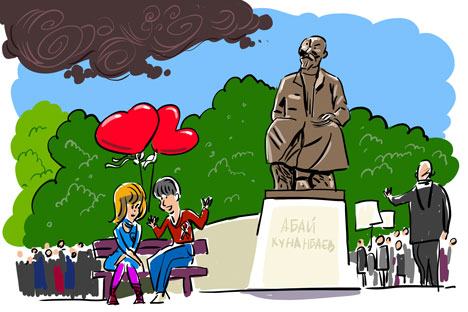

Drawing by Alexey Iorsh

Couples of all ages talked and tweeted about love and politics in the shadow of fresh leaves, wet after the early summer rain. This “Occupy Abai” encampment, spontaneously set up in our Chistye Prudy (Clean Ponds) neighborhood early last month, transformed the posh environs with an atmosphere of hope, change, and more surprisingly, romance.

Even after police attacked the campers and harassed

activists, neighbors and friends returned for evening talks in the park. To an

outsider, the scene would hardly recall Egypt’s Tahrir uprising or even of

Orange revolution in Ukraine – Abai is too relaxed, too happy, with hundreds of

protesters gathering to read anti-Kremlin poetry or listening to lectures on

the Arab Spring.

Many young participants spent their days and nights on the plaza, surrounding the statue of the revered Kazakh poet-philosopher Abai Kunanbayev, a cultural reformer who died in 1904. One wonders what Kunanbayev would have thought about the State Duma’s new law cracking down on protests - and increasing the fine to $9,000 for participating in non-sanctioned protests like the kind hosted at Clean Ponds. What would he have thought about the opposition leaders arrested for protesting, or the homes raided by investigators this week?

The protesters said they were left with unforgettable memories - whatever their political legacy. In recent weeks, two couples showed up at the camp in wedding outfits. Dozens kissed and hugged under umbrellas and sleeping bags around the park. Among the happy campers were 18-year-old Petr Faber and his first love, Polina, who met during Occupy Abai.

Occupy Abai encampment in centeral Moscow. Source: Olga Kravets

It is unclear what exactly inspired the romance mixed with the politics. May in

Moscow can be exquisite and delightful and more romantic than any other month

of the year. Then again it could have been the women’s colorful,

light dresses, nights spent sharing the same blankets on the grass, white

ribbons on their chests to symbolize the anti-government movement, or the

highly charged warm nights falling over Moscow.

The opposition camp became the main event of my neighborhood. We observed as an area of about twenty blocks - between the Clean Ponds park and Kitai Gorod, or China Town, metro stations -- began to show strong signs of community. Crowds arrived, some with kids or with parents, to discuss revolutionary plans or criticize the existing political system around nearby cafes and restaurants. The campers shared free sandwiches, books and CDs, and presented newcomers with handmade white origami flowers – a pleasant gift from a stranger.

For a few days, the Clean Ponds News came out in the style of dissident self-publishers. In fact the whole encampment was born, and then quickly grew, from one Twitter post by blogger Alexei Navalny on the night of Vladimir Putin’s inauguration on May 8th. Navalny called for protesters to gather at night around the monument of heroes of Plevna outside Kitai Gorod metro to take a walk to Clean Ponds. “If police approach, just chant, ‘We are taking a walk! We are going for a walk!’” Navalny, illuminated by dim street lights, instructed the crowd. (That same day, police had clubbed and arrested dozens of opposition activists all around Moscow and at Plevna. But that did not spoil the walk, or spring in Moscow.)

Participants contributed thousands of rubles to buy yoga mats for campers to

sit on and plastic covers to protect them from the rain. I shared my feelings

about the new Moscow vibe with the editor-in-chief of the independent New Times

magazine, Yevgeniya Albats, who was also out strolling at night. We both

remembered that not many people shared sandwiches during the cold nights of the

hostage crises at a Moscow theater in October 23-26, 2002.

“This is a different year and a different Russia,” Albats said, as he watched protesters. To opposition leaders like Olga Romanova, Occupy Abai proved that the movement is a “self-educating community experience, one that later spread to more opposition encampment settlements” around Barikadnaya metro station.

As Petr and Polina were holding hands in the dark park by the pond, Faber

explained to his girlfriend why he had joined the protest. Faber’s father, a

widowed art teacher, fell a victim of scam and was arrested on suspect of

fraud, “without any chance to have a fair court hearing,” he said. “Polina

now understands better why we protest against corrupt education and court

systems. My personal example was an important illustration for her.”

The day the Clean Ponds park was stripped of its encampment by police, our neighborhood seemed again lonely and abandoned. I had been touched and inspired by the creative crowd. Protesters presented our neighborhood with a hope that maybe one day the entire country might feel uplifted, in love, and ready for a sincere talk.

And here we are, on the eve of what opposition figures say will be the first mass demonstration of Putin’s third term. I only know that I miss my pioneering neighbors, and wish them a safe return.

Anna Nemtsova is Moscow correspondent for Newsweek and The Daily Beast

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox