Protests show no sign of stopping

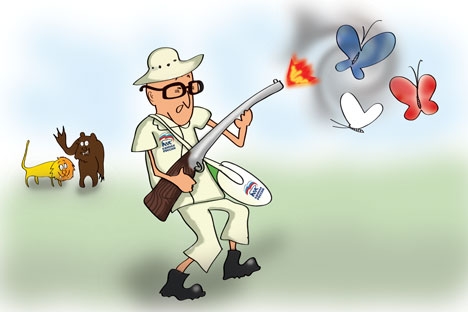

Drawing by Niyaz Karim

The demonstrations that took place in Moscow on June 12, Russia Day, proved that the new sanctions against protests will not prevent the people from showing their discontent.

Last week, the Russian parliament passed new

legislation that dramatically increases penalties for administrative violations

during public protests. The bill was specifically designed to rein in street

activity, and took just a few days for lawmakers to pass it.

Those who opposed the law marched out in protest

during the debates in the States Duma, but the votes of the pro-government

United Russia deputies were enough to pass the bill.

This heavy-handed law is a clear government

reaction to the street activity that has increased in Russia’s big cities since

December.

The first protest, the largest since President Vladimir

Putin came to power in 2000, was a public outcry against fraud during

December’s State Duma election. This was followed by other protests, particularly

on the eve of Putin's inauguration in May, which ended with more than 400

detainees. According to eyewitnesses, both sides acted tough: cops retaliated

harshly against the actions of some violent provocateurs among the protesters,

inciting greater tensions.

Right after these riots, the new law was crafted,

showing that authorities will resort to a policy of maintaining order at the

expense of freedom of assembly.

This is a clear signal to the public that

authorities consider these demonstrations to be violations of public order

rather than a legitimate demand for change. Protesters are, in fact, now

equated with street hooligans.

However, according to many experts, these steps by the government may cause a backlash against the government, leading to larger protests actions in the fall.

A recent study conducted recently by Olga

Kryshtanovskaya, head of the Center for the Study of the class rule at the

Russian Academy of Sciences, shows the protesters' core is broadening.

Authorities should be more scrupulous in the steps they take, she says; this

civil unrest won't disappear so long as the underlying conditions

persist.

First among these conditions is the authorities'

total domination in most areas of public life. This is the root cause of the

extensive corruption and inefficiency in public services, which, in turn, cause

profound economic and social dysfunctions.

That's why one of the key tasks for Putin's new presidential term is to forge relationships with social groups that have made plain their discontent with the current course of government. The authorities' ability and willingness to launch a broader public dialogue and to take into account different points of view presented on the civic stage could largely determine how successful Putin’s latest presidency will be.

While the citizens of small towns with old

Soviet industrial structure still firmly support Putin's form of stability,

according to Lev Gudkov, a leading Russian sociologist and head of the independent

Levada Center, the wealthy, more creative and educated big city dwellers,

particularly in Moscow and St. Petersburg, are calling for urgent political

reforms involving the judicial and electoral systems.

This is the first time in more than a decade that

such a visible demand for greater public involvement in governance has been

seen. It is clear now that the social contract between the society and the

authorities tacitly made in early 2000s is running out and needs to be replaced

by a more democratic agreement.

The essence of this old understanding looked

like this: authorities don't pry into the private affairs of the public, and

the public doesn't pry into the political activities of their ruling class.

The situation is changing now, as progressives demand a real dialogue with authorities and more involvement in social and political life.

The irony is that this demand comes in an

environment that itself arose from the first two terms of Putin's presidency

and the course he held.

During these years, a wealthy urban middle class

emerged and took shape, and it is this group that took to the streets in

December. These voices of protest were able to rise and be heard largely by

means of the new communication technologies that have so expanded in the

digital age. According to comScore Inc., by the end of 2012, "The Russian

Internet audience continued to grow and surpass Germany as the largest online

market in Europe."

This rapid surge of the use of internet and

social networks is one of the most important changes in Russian society in recent

years, although the authorities have yet to comprehend its significance.

However, even with these new sanctions against street activity it would be a mistake for the government to believe that the public will be satisfied just to resume its internet activity in chat rooms. A recent study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that "Following a winter of discontent, Russians express an increased appetite for political freedom. Compared with just a few years ago, more Russians believe that voting gives people like themselves an opportunity to express their opinion about the country's governance... and greater numbers see freedom of the press and honest elections as very important."

The question remains whether the authorities are willing to concede. So far, they are not, and this political shortsightedness may bring about some of the worst political turmoil Russia has seen in the last decade.

Svetlana Babaeva is a senior news analyst at RIA Novosti.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox