Drawing by Natalya Mikhaylenko

The start of a new school year is a good reason to take a look at the state of our secondary education. It is average at best, worth about a C minus. Certainly, there are a great number of first rate schools, lyceums, gymnasiums and institutions with specialized programs. The rest, however, are just bad, or even worse than that. I think that assigning to the state the duty of giving each and every student a complete secondary education is an absurdly utopian idea – and many developed nations share my view. What the government actually must be expected to do is provide equal opportunities for everyone to receive such an education. You can seize upon these opportunities, or you can let them pass you by, and the latter may be the fault of the government, or even families and schoolchildren themselves. In this scenario, the government and pupils are both to be responsible, but for different things.

How Russian teachers make ends meet

Russia celebrates ‘Day of Knowledge’

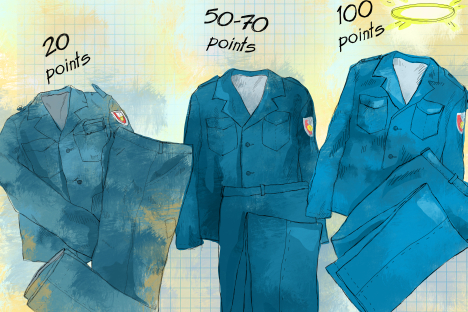

You are always going to get that group of students who perform badly in school and who have no interest in improving their grades. They have the same opportunities as everybody else, but they do not take advantage of them. In this case, the opportunity should be considered unused, no certificate should be issued, and schools should not be held accountable for the outcome. We cannot continue with these double standards any longer: how can a pupil who scores 20 on his or her exams receive the same certificate as a pupil who scores 100? It is corrupting our society.

What, then, is the government's task? It has many. First, it must work to raise the salaries, status and prestige of teachers in society. But not all teachers, as there are many who are simply incapable of self-improvement and are frequently reluctant to make an effort. The unified state examination (state standardized test) is just one way to improve education, and the fact that many teachers are fighting it is proof enough for the government and society of those who do not want to improve. Therefore, there must be a differentiated approach to raising teachers’ salaries and status.

Secondly, teachers need to update their knowledge and retrain on a continuous basis. The best place to do this is in a traditional university; advanced training institutions do the worst job. What should teachers be taught? Apart from the rapidly changing knowledge in their respective areas of specialization, they have to become comfortable with the values and mechanisms of activity-based learning, since the new standard of education rests on its major concepts.

Thirdly, even school administrators need to be upgraded and retrained on a regular basis, and those coming in to replace them need to be trained too. Such programs are currently offered by the Higher School of Economics and its branches, but they can also be set up at many other universities, provided that serious reform is implemented. This includes embracing the societal functions of the university, which has now become a must for western universities.

After this, we need to drop the rhetoric about teacher training reform and actually get down to business. Teachers who are supposed to be experts in their respective fields must complete bachelor's and master's programs without any reduction of knowledge. We also need to restore extra-curricular education at schools, which has all but disappeared from many educational facilities.

Finally, the Soviet school system deliberately excluded parents from its activities. Consequently, after four generations, we are dealing with an established pattern of parental behavior: estrangement from the schools and a perception of schools as a sort of educational storage room for their kids. Naturally, schools are held accountable for everything.

Student success has now become a very topical issue. Things seemed decent while schools assessed their success internally. But, as soon as the first unified state exam revealed that half of the pupils were leaving school with barely a passing grade, it clearly became an issue of national security. The government has figured out what to do about the increasing number of children with disabilities; it is getting a clearer idea of what to do about migrant children; the problem of rural schools has long been recognized, although it is still far from being solved. Meanwhile, at least half of those 'unsuccessful pupils' end up starting average urban families. This is largely because they do not understand what consistently low grades means for a child's future. And how can they, when they 'earned' their certificates for a mere 20 points?

It must be clear what I want to say by now: the government has to be responsible for creating equal opportunities. Meanwhile, the parents and the students must, in turn, be responsible for the way they utilize the opportunity. Anything below 20 points in a unified state exam must result in no certificate; anything below 50 points should present problems for entering budget-funded spots in higher educational institutions, and anything between 20 and 50 points should lead to blue-collar professions or technical specialties. And while massively aloof parents (and equally massively negligent high school students) are sure that the government will still cling desperately to the utopian idea of obligatory universal student success, their behavior and diligence will hardly change at all. Responsibility and diligence are traditionally not the strongest points for a considerable part of our nation. It is time to cultivate these qualities – naturally, starting with schooling.

Lev Lyubimov, Deputy Academic Supervisor, Higher School of Economics.

The opinion is first published in Russian in Izvestia Newspaper.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox