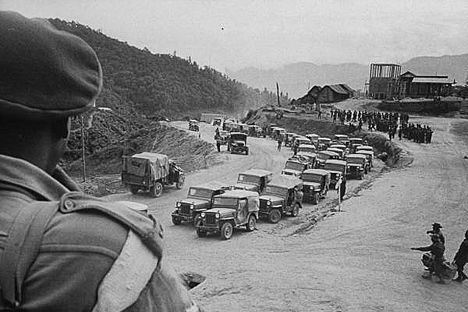

Putting behind 1962 war with China. Source: Press Photo

Mukut Mithi is not a regular columnist. He is an active, politician with a long inning ahead, conceivably. He has already climbed many heights and is currently a member of Rajya Sabha, the Upper House of the Indian Parliament, representing the state of Arunachal Pradesh, which borders China, and which China claims as its territory.

Mithi used to be the chief minister of Arunachal Pradesh. And most importantly, he belongs to the ruling Congress Party. This much needs to be said at the outset to get the point across that he is no ordinary, run-of-the mill politician. That is what makes his opinion matter on issues concerning India’s relations with China.

In the welter of opinion-making in India in the recent weeks on the 50th “anniversary” of the conflict between China and India in 1962, Mithi’s opinion stood out for its out-of-the-box thinking.

Mithi’s idea can be summed up as follows. Arunachal Pradesh is rich in resources – forests, hydropower potential, minerals such as oil and gas, dolomite, graphite, coal, quartzite, limestone, marble, etc. Yet, it is lacking in development, and like the northeastern region as a whole, its integration with the rest of India remains far from meaningful. Arunachal Pradesh can benefit in development if it is transformed as a trade route with China; Tawang, the ancient Tibetan-Buddhist centre, can welcome tourists from China, and do “serious business” with China. He wrote:

“I suggest we must work towards converting the 1962 war routes as trade and friendship routes. In October 1962, Chinese soldiers occupied Tawang located in the western part of Arunachal, then called North East Frontier Agency, or Nefa. On east Arunachal, Indian and Chinese soldiers fought at Walong. We all grew up with stories around those battles.

“I strongly believe that after 50 years, both New Delhi and Beijing must enter into a serious dialogue to make Tawang-Bum-La and Walong-Rima trading routes a reality. Let those be named as friendship routes.”

To what extent Mithi was doing kite-flying for the Indian establishment one can never tell. But it stands to reason that he also would know the pitfalls of talking out of turn on such a sensitive topic at a poignant juncture in the India-China relationship.

However, Mithi’s has been a rare voice. The overpowering feeling one gets while wading through the literature that appeared in the last few days of the “anniversary” of the 1962 conflict is that the bitter memory of the military defeat at the hands of the Chinese lurks just below the surface in the Indian pundit’s consciousness. Logically, a normalisation of relations between India and China cannot happen unless and until the border dispute is resolved. Yet, the protracted talks have not yielded significant results. The focus, therefore, has come to be on keeping peace and tranquility on the disputed border regions where friction remains high, unsurprisingly, as the soldiers of the two countries patrolling the disputed tracts cannot but help running into each other.

Compounding the frictions is that Xinjiang and Tibet on the Chinese side and Jammu & Kashmir and India’s northeastern states remain in varying degrees of volatility. Both China and India have adopted a pathway based on the belief that economic growth holds the key to the removal of political alienation in their respective disaffected regions, but the results have been mixed so far. In relative terms, China has made far greater leeway than India on the path of development of Xinjiang and Tibet, while India is leagues ahead of China in introducing participatory politics and representative rule in its northeastern states. Yet, the results have been patchy. For both, the disaffected regions also happen to be peripheral territories in their far-flung lands. Arguably, they have much to learn from each other’s experience.

Mithi’s proposal fits into this paradigm. It also bears resemblance to India’s current approach toward the intractable Kashmir problem involving Pakistan. Without prejudice to each other’s stance on the Kashmir problem, India and Pakistan have agreed to begin border trade at designated points along the Line of Control [LOC] separating the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir and the region that India calls “Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir”. The easing of the restrictions on border trade and on the movement of people can be seen as confidence-building measures but then, they have also tangibly brought down tensions and can have an economic logic as well, especially if the trend of steady improvement in the overall climate of India-Pakistan relations in the recent years continues.

The Indian thinking is that the border with Pakistan along the LOC can be made “irrelevant”. Mithi does not postulate it in quite that way, but what his idea amounts to is to make the border dispute with China somewhat “irrelevant” in a near term so that it can be revisited in a calmer setting later. Suffice to say, Mithi’s approach takes us back to an a priori history when today’s “badlands” used to be for centuries ungoverned territories situated between empires and kept them from rubbing against each other.

Mithi’s is a tantalising thought because any resolution of the India-China border dispute as such is nowhere in sight. If anything, as India steps deeper into the era of coalition politics, consensus making in the domestic opinion regarding such an emotive issue is going to be next to impossible. China may be able to show flexibility (provided, of course, the political will exists in Beijing) but even then, arguably, no government in Delhi can match that flexibility. Clearly, the Indian political scene remains highly fragmented with various interest groups pulling in different directions. The government’s difficulty to settle the Siachen problem through a compromise solution with Pakistan underscores the prevailing Indian predicament.

In international politics, analogous situations never quite exist. But there could be similarities and indeed comparisons can be drawn. Of late, there has been talk of Russia inviting Japan to cooperate in the joint development of the Kuril Islands. The backdrop is of a Japan, which would have growing interest – or imperative need, depending on how one looks at its stagnant economy today – in engaging a resurgent Russia in the power dynamic of the Asia-Pacific region, and of a Russia, which is also keenly innovating its economy and is in need of trade, technology and investment from Japan, especially for the development of its vast Siberian and far East regions.

In the case of India and China also, the trans-border connectivity and cooperation could open up opportunities for mutually beneficial economic interaction with regard to the development of the two countries’ peripheral territories – India’s northeast and China’s southern Yunan-Tibet regions.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox