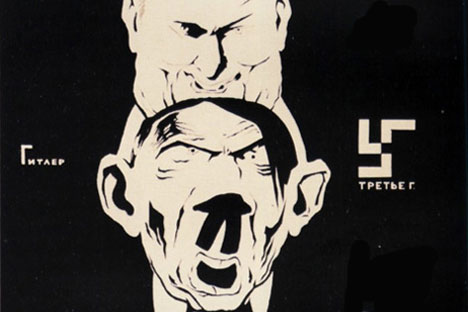

Click to enlarge the image. Source: Dmitry Moor

Back in 2005, when the Russian Government announced that the November 7th (October Revolution Day) holiday would be cancelled in favour of November 4, which it termed Unity Day, I was elated. I didn’t have a particular problem with the day marking the Bolshevik Revolution but since Russia had moved on from the days of the USSR, what was wrong with the country having a national holiday on my birthday?

The thought of not having to work on my birthday as long as I lived in Russia and the fact that everybody would be relaxed made me happy. Of course, this elation vanished when all the assorted low-lives, psychopaths and fringe elements of society decided to hijack this day in Moscow by marching under Nazi banners while wearing clothes and hats with Nazi symbols. The television channels gave these people enough publicity for this holiday to become associated with this march.

It’s easy to get carried away by images from this annual march and reports by human rights organisations about attitudes in the country and assume that a large number of people are embracing Nazi ideals in Russia. Nothing could be farther from the truth! In a country of 140 million, if all of the fringe elements from society get together and rebel against perceived injustices, there may look like there are many people following a particular ideology. However most people outright reject this ideology of hatred and is a matter of great shame for any family in Russian society if someone from the house is connected with these movements.

I remember sitting at the dinner table with the head of a family I was close to, while living in Sakhalin. The wonderful man in his early 60s was visibly agitated that evening. He saw a swastika spray-painted on a garage when he was parking his car. “They should all be guillotined,” he said angrily. He went on tell me about his childhood in post-war Voronezh where it took more than two decades to reconstruct the city after the devastation of the Third Reich. “In those days, if someone said ‘Heil Hitler’ on the streets, it’s not the police that would have arrested him...The public would have lynched him within minutes.”

Being a small town, the Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk police rounded up a couple of 15-year olds who were responsible for the graffiti. Within days, other painted red stars over the swastikas, with the symbolic message that those supporting neo-Nazism would suffer the same fate as the Third Reich did in the 1940s. This is the same Sakhalin Island, where local criminals beat up a group of skinheads that came across from the mainland to terrorise the ethnic Korean community in April 2002.

The shocking phenomenon of Russians admiring Hitler and the Third Reich was a direct result of the lawlessness that engulfed post-Soviet Russia through the 1990s. A sense of lost pride and rebellion against everything that the previous regime stood for was the main reason that neo-Nazis from Europe could find recruits in Russia. The recruits were essentially, young school dropouts from broken homes who lacked any kind of meaning or purpose in life. Most of the people that still proudly display Nazi paraphernalia belong to that generation. With a revival in educational and living standards in Putin’s Russia, there is far less of an inclination for young people to find Nazi ideology alluring.

It’s important to acknowledge that not every person who opposes illegal immigration into the country is a neo-Nazi. There are people who have genuine grievances against illegal immigrants but won’t turn into skinheads and attack Central Asians. Now that there is a great degree of stability in Russia and people especially in cities like Moscow enjoy standards of living that their parents would have never dreamt of, Russia needs to look at the best ways to manage immigration. The current policy or lack of policies is a failure.

As long as citizens of most CIS countries don’t require entry visas to Russia, the country will be attractive for unskilled labour. With Russia looking to reform immigration laws, the best way to stop young people from getting swayed by neo-Nazis is to continue to educate them about the evils of the ideology. Young Russians tend to resist force in a way that few do in other parts of the world. Banning Nazi propaganda and ideology would send these groups underground and actually make them popular. It may actually become fashionable to be part of such a movement.

One of the worst ways to insult someone in Russia is to call him or her a Fascist. Most people overwhelmingly reject neo-Nazi ideologies, but a ban could backfire and push those sitting in the fence towards embracing something silly but dangerous as a “cool” way to stand up to the state.

I support my case with reference to an incident that dates back to 2005 in Voronezh. A 19-year old Peruvian architecture student was murdered by skinheads in a case that drew a lot of international criticism. What the papers and the television channels didn’t mention was that the rector of the university put up a huge banner at the main entrance with a photo of the deceased student, with a message for the neo-Nazis that read, “You don’t deserve to call yourself Russians.” A Russian friend who was studying there at that time talked about how attitudes began to change among many of his acquaintances after such a powerful message was put up. He was a freshman the year of the incident and said there was a sea change by the time he graduated.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox