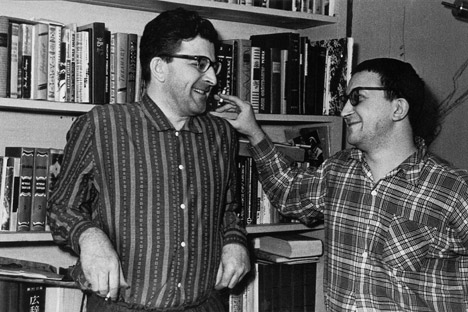

Russia's prominent science-fiction writer Boris Strugatsky. Source: ITAR-TASS

When brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky began writing their first book in 1957, they probably had no idea that within 10 years they would be a truly dominant influence in a vast country. During the 60s and 70s, the popularity of this writing duo was simply incredible – even greater than that of Erich Maria Remarque or Ernest Hemingway, who at that time were the idols of the intelligentsia.

A series of books came out. The authors described the books as “tales”, although in the depth of the issues they raised they left many novels, and virtually every one of them became a bestseller. Monday Begins on Saturday, Hard to Be a God, Beetle in the Anthill, Definitely Maybe and many others sold like hot cakes, despite their huge print runs. In those years, there was probably no book-loving person in the country who didn’t read the Strugatskys.

They were not only the most famous science fiction writers in the country, but aslo they were just about the only Soviet fantasy writers who were recognized as classics in the genre throughout the world. Their books were translated into more than 30 languages, and by the beginning of 1991, the brothers had had 321 books published in 27 countries. As one of their fans put it, “unlike the host of other science fiction writers, these authors really knew what a tensor field and the Schwartzschild metric were.”

The Strugatsky brothers dealt with science-fiction stories and describe their books as "tales." Source: ITAR-TASS

It was Boris, the younger brother, who was responsible for the tensor field. Unlike his humanities-oriented brother (Arkady graduated from the Moscow Military Institute of Foreign Languages and was a qualified expert in Eastern and Japanese studies), he was a physicist through and through – a graduate of the famous Mathematics and Mechanics Faculty at Leningrad State University with a diploma in astronomy, who worked at the Pulkovo Observatory for many years.

For a long time, Boris was overshadowed by his older brother. Arkady Strugatsky’s life story included more events, more tragedies: He was evacuated with his father from Leningrad during the Siege (and his father died in his arms), was called up into the army in Orenburg, trained at the Aktyubinsk Artillery College, served in the army for more than ten years, fought in the Soviet–Japanese war and worked for many years as an editor, publishing the first books by the classics of Soviet science fiction.

Boris’ life was almost ordinary. Yes, there was the first and most dreadful besieged winter in Leningrad in 1941, which he lived through as a ten-year-old boy. But after that, it was just like anybody else’s: He finished school with above-average marks, studied at Leningrad State University, went on to postgraduate study, worked at the Pulkovo Observatory and, from 1964, pursued his passion as a professional writer full time.

From then on, it was all about books. Books in which he and his brother did perhaps the most important and most difficult job of their life – showing people the future in which they would like to live. Their multi-volume series of novels about the World of Noon (named after the first book in the series,Noon: 22nd Century) was the second attempt (after Ivan Yefremov’s books) in Soviet literature to paint an extensive picture of communist society. It was the second, the last and perhaps the most successful.

Yefremov’s characters are too different from us: by and large, they are not really people any more. But the heroes of the World of Noon are just like us, only better. Like us, they swear, dream, fall in love, rush about in search of the right decision, make mistakes and even commit crimes. But for all this they are purer and happier, for the simple reason that they live in a world created by people for the enjoyment of others.

The World of Noon was completely alive, and that was where its strength laid, which is undiminished to this day. It is surprising but true that, while our country was building communism, film-makers were producing all kinds of works by the Strugatsky brothers –Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel, Monday Begins on Saturday, Roadside Picnic (which was turned into Tarkovsky’s Stalker) and Definitely Maybe – but never anything from the World of Noon series.

Only now, when the idea of building a bright future has been dropped, have two large-scale film adaptations of their most important “Noon” books – The Inhabited Island and Hard to Be a God – been released.

Whether by coincidence or not, the Strugatsky brothers’ partnership did not outlive the Soviet Union. In 1991, the country fell apart, and Arkady Strugatsky’s life ended not long before the Belovezh Agreement in October 1991. The younger brother was left alone, and after declaring that there was no longer a writer by the name of “the Strugatsky brothers” and never would be again, he continued to “saw through the thick log of literature with his usual two-man saw but without a mate”.

Over the next 20 years, he published just two books (under the pen name “S. Vititsky”); Search for Designation or Twenty Seventh Theorem of Ethicsin the 1990s and The Powerless Ones of This World in the “noughties”. The last few years were very difficult for him – both physically (Boris had several heart attacks) and psychologically.

The evolution of his views was not accepted by many of his admirers. Strugatsky had changed from a romantic communist into an ultra-liberal, a supporter of economic “shock therapy”, and then into a gloomy sceptic. He had to live for a long time in a world in which Noon had failed.

Many people are now saying, “it’s the end of an era.” This is said every time a famous figure dies, but this time an era really has ended. For several years now the patriarchs, the authors of the great generation who made science diction a fully-fledged branch of literature, have been leaving this world. We’ve lost Simak and Azimov, Heinlein and Dick. Clarke and Lem, Sheckley and Vonnegut left us comparatively recently. And this year has swept up the last remains – Harry Harrison, Ray Bradbury and Boris Strugatsky all died in 2012.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox