Was the Magnitsky Act Inevitable?

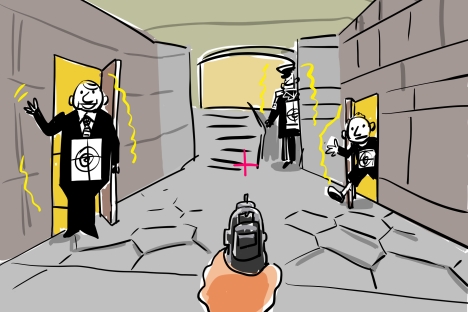

Drawing by Alexey Yorsh. Click to enlarge the image

In the closing days of the year, all the attention has suddenly turned on Russian parliamentarians: ignoring the distractions of the looming holiday break, they produced a “symmetric” response to the Magnitsky Act. The Magnitsky Act, adopted by the U.S. Congress just a few weeks ago, will ban entry in the United States and freeze financial assets there of Russian officials suspected of human rights violations.

In an attempt to punish the United States for the act, which Moscow considers blatantly anti-Russian, the State Duma developed a piece of legislation of its own: the so-called Dima Yakovlev law named after a Russian boy who was adopted by an American family and later died as a result of a tragic accident.

Related:

U.S. families banned from adopting Russian children

Similar to the Magnitsky Act, the Dima Yakovlev law will ban entry into the country of Americans responsible for the violation of rights of Russian citizens; it will also make it illegal for non-profit organizations engaged in “political activities” to accept funding from U.S. citizens. Yet the most controversial provision of the Dima Yakovlev law is to ban the adoption of Russian children by American parents. Passed by the Duma on Dec.21, the law was approved by the Federation Council on Dec. 26; Russian president Vladimir Putin signed the law on Dec. 28.

The appearance of the Dima Yakovlev law resulted in a tsunami of public protests, the scale and strength of which surprised everyone, including, perhaps, the Russian lawmakers themselves. The major argument put forward by the critics has been that the implementation of the law will predominantly harm the interests of Russian orphans, especially those with disabilities, which, while being morally wrong, may also place Russia in violation of a number of its international obligations.

Russian daily Novaya Gazeta reported that its website collected more than 100,000 signatures calling on the Duma to repeal the law. Joining the ranks of those opposed to the law were prominent members of Russia’s political establishment, including Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Minister of Education Dmitry Livanov.

Curiously enough, in the heat of the argument over the appropriateness of Russia’s response to the Magnitsky Act, the act itself was all but forgotten. This is unfortunate as Russia must learn a few important lessons from the whole Magnitsky affair. The most important is that the adoption of the Magnitsky Act by U.S. Congress was not inevitable.

When the former boss of Sergei Magnitsky, British citizen Bill Browder, outlined the idea of a Magnitsky bill, it was met with significant skepticism on Capitol Hill. Moreover, the Obama administration from the very beginning expressed its opposition to the bill. But Browder persisted and kept lobbying for the bill. And what did Moscow do in response? Nothing.

Apparently considering Browder too irrelevant to pay attention, Moscow watched quietly while the Magnitsky bill gradually strengthened. And yet the only thing Moscow had to do to kill the bill in its cradle was to clearly articulate something that has been long known: that Browder and Magnitsky were suspected of committing serious financial crimes.

True, in the summer of 2012, a delegation from the Federation Council did arrive in Washington and try to make this point to American lawmakers. But it was too late: by that time, the sponsors of the Magnitsky Act in U.S. Congress were so heavily invested in this project that it was simply politically impossible for them to change their positions.

It is also worth noting that in his lobbying crusade, Browder was actively assisted by numerous anti-Russian groups, including those organized by the members of the Russian diaspora in the U.S. Meanwhile, the much needed and long-talked-about pro-Russian lobby in America still does not exist. Moscow stubbornly refuses to accept the rules by which the American political system operates and seems to believe that the only way to influence U.S. decisionmaking vis-à-vis Russia is through presidential summits.

The adoption of the Magnitsky Act is clear evidence that this approach is wrong: President Obama, while opposing the Act, could not spend his political capital on “fixing” things for the Kremlin. Moreover, if Moscow will not change its attitude—that is, will not begin actively promoting its interests in Western countries, additional anti-Russian acts will follow.

The Magnitsky Act itself has no real significance: the figures on the Magnitsky list are unlikely to apply for American visas and they had plenty of time to liquidate their assets in the U.S. (in case they ever had them). The problem for Moscow is that the adoption of the Magnitsky Act will serve as a trigger that will set in motion the appearance of similar laws all over the European Union. Should this happen - and this seems to be already happening - Russia may kiss goodbye the visa-free travel agreement with EU it is so actively seeking.

As for a “symmetric” response to the Magnitsky Act, Russian parliamentarians would be better off to ban entry to Russia of all sponsors of the bill in the U.S. Congress: 39 Senators and 81 House representatives. Some of them occasionally travel in Russia on business, so such a ban will indeed affect them. Besides, U.S. congressmen have such an oversized ego that they will take close to heart any ban including their name. They will get the message.

Eugene Ivanov is a Massachusetts-based political commentator.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox