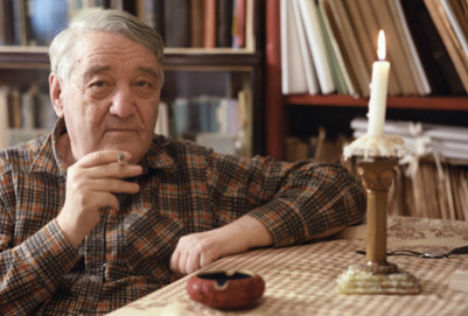

Lev Gumilev, a prominent Russian historian and ethnographer. Source: Press Photo

The son of two Silver Age poets – Nikolai Gumilev and Anna Akhmatova – he survived several arrests and years of imprisonment in GULAG camps. During the Second World War, he volunteered for the Red Army and served in an anti-aircraft artillery regiment. He fought bravely and took part in the liberation of Poland and the Battle of Berlin.

Lev Nikolayevich Gumilev was born in Tsarskoye Selo on October 1, 1912. After his parents divorced, he lived with his paternal grandmother in her estate in the Tver region, where he spent most of his childhood. A voracious reader, he developed a passionate interest in history.

Being the son of well-known poets was both a great joy and a heavy burden that caused plenty of suffering to him. He had to hide away his love for his dear father, whom he worshipped, and he had to be careful not to mention his mother, Anna Akhmatova, too often either. The latter was much easier to do, given a chilly relationship between him and Akhmatova.

Nikolai Gumilev and Anna Akhmatova with the son - Lev Gumilev. Source: Press Photo

Things got really tough if not dramatic for the young Gumelev in the early 1930s. All doors were suddenly closed to him. He was labelled a “public enemy’s son” and could not enter the Leningrad University. He earned his living as a manual worker and later as an assistant on geological expeditions to the Sayan and Pamir mountains. Anyway, he finally managed to get the university at the faculty of history. Learning came easy to him. He was well-read and knew foreign languages. But he felt isolated socially. Most of his fellow students avoided him, and professors would grow suspicious the moment they heard his name and gave him the cold shoulder and informed on him. His studies were interrupted by a string of arrests.

Gumilev, or Big Leo, as his friends nicknamed him, once said that it was his favourite studies into which he had immersed himself that helped him through his hardships. History, geography and ethnography preoccupied his mind and stirred his imagination.

“I was arrested four times and put under investigation six times,” Gumilev recalled. “In 1939, I was brought back from a northern camp to the Kresty prison in Leningrad for re-investigation and subsequent execution by shooting. But at that same time, purges were launched at the NKVD, and my executioners themselves received the death penalty. My situation changed. I was sentenced to five years and sent to Norilsk where I served four years.”

It was in the Kresty jail that Gumilev made an important scientific discovery.

“As I sat in my cell, I saw a ray of light fall through the window on the cement floor. The light penetrated even into the dungeon. Suddenly, an idea flashed through my mind that the movement of history is also powered by a certain energy. And then, spontaneously, I started pondering on the motivation of the deeds of individual people in history. Why, for example, did Alexander the Great invade India and the Central Asia despite obviously being unable to maintain his grip on or even loot those lands as he couldn’t deliver the looted trophies to his native Macedonia? It occurred to Gumilev that Alexander the Great had been driven on by some inner push, some natural impulse. He called it passionarity – an irresistible inner urge to purposeful activity, the capability of sustained super effort in the name of a lofty, though sometimes illusory goal.

“I sprang up from my bunk and shouted: ‘Eureka!’, Gumilev recalled. “My fellow inmates, there were about eight people in the cell, looked at me morosely, thinking that I’d gone mad and saying: ‘Here’s yet another crank!’ How could they know that just a minute ago I found a clue to a puzzle that haunted me for the past few weeks?”

That discovery changed Gumilev’s life once and for all.

In Norilsk, Gumilev was a mine-digger and a geologist. He even found a large iron ore deposit. In 1944, he was granted early release and permission to volunteer for the army.

After the Second World War, Gumilev was demobilised in the rank of private and returned to the university. He graduated in 1946, obtained his first academic degree and moved to the Museum of Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR as a researcher. But then, again, they came for him. It happened in 1949.

“You are dangerous because you are educated,” prosecutors said to him. “Take another name and we will leave you in peace”. But not for the world would he betray his father’s memory. Gumilev was sentenced to ten years in camps. Luckily, he only served half his term. In 1956, three years after Stalin died and de-Stalinization began, Gumilev was acquitted and fully rehabilitated due to the absence of elements of crime in his actions.

Gumilev did not believe in universal human culture. He maintained that humanity as a unity exists only at the species level, whereas behaviourally, it is divided into super ethnoses, ethnoses and sub-ethnoses, each having its own culture. The Chinese, the West Europeans, the Arab Muslims, Indians and other super ethnoses and ethnoses all developed cultures of their own, hence different and sometimes polarized perceptions of the good and the evil among various ethnoses.

Gumilev illustrated the inequality of civilizations by a simple example, says Academician Alexander Panchenko. Once, he read a story by famous explorer Thor Heyerdahl about his meeting with a middle-aged cannibal tribesman on the island of Matu Hiva. The tribesman spoke pretty good French.

“Is it true that you ate other people?” Heyerdahl asked.

“Yes, it is. We waged wars against neighbouring tribes. There were casualties. And we ate them.”

“It’s awful!” Heyerdahl exclaimed.

“And don’t people, in Europe, wage wars?” asked the man.

“They do, and do it a lot!”

“And they kill other people, don’t they?”

Yes, they do.”

“What do you do with those killed?”

“We dig them into the ground.”

“We at least eat them, and you dig them into the ground. Isn’t it awful?” the tribesman replied.

The equality of civilizations? But one civilization is neither better nor worse than another. These are two absolutely different civilizations and they should try to form a peaceful co-existence, learning from each other and teaching each other, academician Panchenko said.

“We must study the experience of other ethnoses but bearing in mind that their experience is alien to us,” Gumilev wrote. “The Western European ethnos emerged in the 9th century A.D. and has carved a millennium-long path in its natural ethic evolution. That’s why West Europeans are more advanced technologically, have higher living standards and are governed by law, rather than force. As for Russia, it shaped itself into an independent super ethnos in the 14th century A.D., five centuries later than Western Europe. We and West Europeans always felt that gap, that inequality… That explains why a mechanical transition of West European traditions to the Russian soil brought so little result. Our age, our level passionarity implies quite different behavioural imperatives.

The humanities give us much knowledge but little understanding, Gumilev used to say. He created a new branch of science – ethnology, which explores the genesis, evolution and disappearance of ethnoses from the point of view of passionarity.

“There once were Philistines, Chaldeans, Etruscans and Macedonians. They no longer exist. Once upon a time, there were no Englishmen, Frenchmen, Swedes or Spaniards. But why do these new ethnic entities emerge and start to dissociate themselves from their neighbours?

Every new ethnos passes through a number of evolutionary stages. Just like humans, ethnoses are born, then mature into adulthood, age and die. In Gumilev’s opinion, this process, called ethnogenesis, is closely connected with the biosphere and is powered by a mutation, the so-called passionarity push that becomes a hereditary feature. But what causes these mutations – cosmic rays or God. Gumilev leaves that question unanswered.

Rejected by the academic science, Gumilev’s ideas that were relatively unknown until Gorbachev’s perestroika of the late 1980s when his first books were published along with his father’s poems.

His passionarity theory aroused huge interest. He delivered a series of public lectures and often appeared on television.

Just as we can’t force the volcanoes of the Pacific Ocean not to erupt or trigger devastating tsunamis, so a poet or a scientist cannot be forced into some or other activity, Gumilev once remarked.

Shortly before his death, he said: “After all, I am a happy person. All my life, I did what I wanted to do and wrote what I thought, whereas others did and wrote what they were told”.

Big Leo died in 1992 at the age of 79. He was buried at the Nikolskoye Cemetery at the Alexandro-Nevskaya Lavra monastery in St. Petersburg.

First published in the Voice of Russia.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox