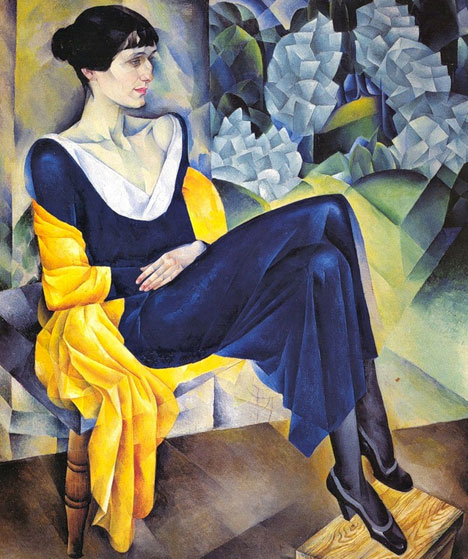

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova by Nathan Altman, 1941. Source: wikipedia

When her son Lev was arrested in 1938, Anna Akhmatova burned all her notebooks of poems. From then on, she memorized everything she wrote, to recite afterwards only in private readings with trusted friends.

Lev’s father, Akhmatova’s first husband Nikolai Gumilev, had been killed for his supposed role in an anti-Bolshevik conspiracy. But Akhmatova knew her son was probably also targeted because of the uncompromising nature of her own verse.

Her transition to the oral tradition also meant a change in her style: more fragmentary, more visual and, above all, more resonant. That was her strategy for surviving and safeguarding the collective memory of her people.

As a poet, she could not save the victims of Stalin’s Terror, the purges, or the Siege of Leningrad during World War II. But her transparent verses could preserve memory, and save it from a second death: Oblivion.

Akhmatova reading her poem 'When at night I'm waiting her arrival.' Source: Youtube

A generation passed through me

As the terrible events mounted in Russia and the suffering of her people grew, Akhmatova’s voice became stronger and more committed to the weakest victims. She lived through the fall of the empire, the October Revolution and two world wars. Akhmatova endured the terror of Stalin and the persecution of her writer-friends who belonged to The Silver Age: Mandelstam died on route to the Gulag, Tsvetaeva hanged herself and Pasternak was persecuted till his death. Akhmatova was officially silenced in 1924, and did not publish again until 1940.

“An entire generation has passed through me as if through a shadow,” she wrote. Despite her poverty and delicate health, Akhmatova’s generosity and solidarity with her family and friends remained a part of her character.

Between 1935 and 1940, she composed “Requiem.” In this, her most famous poem, she laments the execution of Gumilev, her first husband; the arrest of her third husband Nikolai Punin; and the imprisonment of her son Lev. But “Requiem” was also an anthem of the people’s resistance before the power of Stalin; one of the poem’s most powerful passages was written “Instead of a Preface.”

“I passed seventeen months in the prison queues in Leningrad. Once, somebody ‘identified’ me there. Then a woman standing behind me, blue with cold, who of course had never heard my name, woke from that trance characteristic of us all and asked asked in my ear (there, everyone spoke in whispers): ‘Ah, can you describe this?’/ And I answered:/ ‘I can.’ Then something like a tormented smile passed over what had once been her face.”

Anna Andreievna Gorenko wanted to be a poet from a young age. Throughout her life she would forge the image of a mysterious, special woman. Her father, on reading her poems, called her a “decadent poet” and did not want her to use his last name. But she took her nom de plume, Akhmatova, from a great-grandmother, a Tartar princess from the lineage of Genghis Khan, according to family legend.

She was a desired woman as well as a charismatic poet. Her height at 5 feet 11 inches, her extreme thinness, elegant, (some thought haughty) demeanor, long, straight hair tied at the back of her neck, high cheekbones, enormous gray eyes, thin lips and aquiline nose, created a singular look. All this and the spellbinding rhythm of her voice when she recited her poems made Anna Akhmatova an icon of beauty, which many painters, including Modigliani, were compelled to portray.

St. Petersburg was her beloved and lamented city. There she lived an intense, avant-garde, party-going life, where she enjoyed love and sexual freedom, yet it was also the city where she experienced famine, pain, poverty and sickness.

Her drifting, bohemian nature very soon got her cast out of one home — “But, where is my home, and where is my reason?”—although she lived off and on for many years at Fountain House, owned by her third “husband,” Nikolai Punin, an art critic whom she lived with in an insane kind of intimacy that included Punin’s wife and the couple’s daughter. Emotional instability was another challenge of Akhmatova’s life. It was her nature to fall in love easily, but she did not find love in her numerous lovers; she found it in poetry, as she relates in “My Half Century,” a book of her prose and autobiographical sketches, translated by Ronald Meyer.

St. Petersburg was the cultural epicenter of Russia and breeding ground for the avant-garde. Symbolists, represented by Blok, Futurists led by Mayakovsky, Acmeists and artists of all disciplines gathered in a basement, The Stray Dog, where in 1913 Akhmatova became the undisputed queen. A year earlier, she published her first book, “Evening,” with the support of The Guild of Poets, the group who named the new Acmeist movement, in which N. Gumilev, Osip Mandelhstam, Sergey Gorodetsky and of course Akhmatova were key figures. The Acmeists, unlike the Symbolists, demanded clarity in poetry and valued individual experience.

Born: June 11 (23 Old style), 1889, Odessa

Honorary Degree from Oxford University in 1965.

She died near Moscow on March 5th, 1966, and was buried in Komarovo Cemetery, in St. Petersburg.

“Evening” was a surprising success. The poems explored the unhappiness of love, and they became very popular. Akhmatova herself, laid bare her intimacy to readers. In 1914, she published her second book, “Rosary,” which was followed by three more.

On August 1, 1914, when Germany declared war on Russia, Akhmatova’s poetry changed course. “In the morning, still some peaceful poems about other things. But in the afternoon, the whole world is shattered.” From then on, the poetess directed her gaze towards Russia, a land that she loved and would never leave. Years later, when she was reading James Joyce’s Ulysses, Akhmatova would be deeply struck by the sentence, “You cannot leave your mother an orphan,” which she later modified to “You cannot leave your Motherland an orphan.”

Akhmatova’s poetry fully matured with “Poem without Hero,” a work she spent 22 years of her life to compose, and is now recognized as one of the greatest contributions to universal literature. Written in Leningrad, Tashkent and Moscow, “Poem without Hero” (1940-1962) is an epic, heartrending collection of poems where multiple voices and different genres compose the lyric chronicle.

Here again, she wrote of an old self with dispassion: “That woman I once was/ in a black agate necklace/ I do not wish to meet again/ till the Day of Judgement.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.