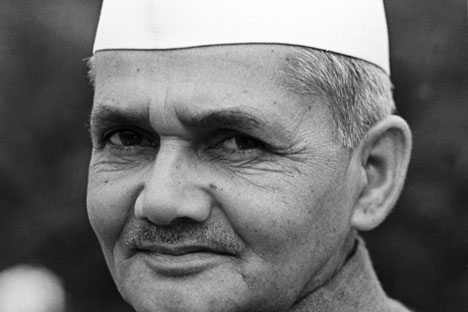

Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri. Source: Yuryi Abramochkin / RIA Novosti

Lal Bahadur Shastri’s untimely demise on account of a heart attack in 1966 in Tashkent was shocking. The strange circumstances of this tragic death, which happened only a few hours after signing the Tashkent Declaration, remain the subject of heated debate, even today, nearly half a century later.

In 2009, Indian journalist Anuj Dhar, known for his investigation of the death of Subhas Chandra Bose, made an unusual request to the Prime Minister of India. Using the country’s new Right to Information Act, he sought the publication of classified information relating to the death of Shastri. Although the request was turned down, the wording of the refusal, which cited raised issues of India’s foreign relations, makes one pause. It is no wonder that such statements cause people to discuss various versions of Shastri's death that are very different from the official one.

The first version appeared immediately after Shastri's death...

On the evening of January 10, 1966 in Tashkent, Shastri and Pakistani President Muhammad Ayub Khan, with the participation of Alexei Kosygin, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR had signed a peace declaration that ended the Indo-Pakistan war. The bloody confrontation in Kashmir and neighbouring regions, claiming the lives of nearly 7,000 people, came to an end thanks to reasonable compromise by both leaders and the skilful mediation of the Soviet Union. According to diplomatic traditions, when negotiations come to a successful conclusion, a formal banquet is held. No disaster seemed imminent. And then at night Shastri, who had just a few hours ago achieved peace for his country, died suddenly.

The sad news shocked everyone. The KGB was called in immediately and they placed the head waiters who had served the distinguished guests at the banquet under temporary arrest on suspicion of poisoning the Prime Minister of India. However, the doctor who accompanied the Prime Minister on his trip and the Soviet doctors, having examined the body, came to the conclusion that he died of a heart attack, which was already his fourth. The waiters were released, and the suspicion of the poisoning was said to be groundless.

However, not everyone believed this. Lalita, the wife of Shastri, pointing to strange bluish marks on his body and claiming that he never had any heart problems in the past, said that her husband was indeed poisoned. The tense political situation in which Shastri had worked and the suddenness of his death seemed to speak in favour of this. At the same time, the Indian authorities found no reason for an autopsy. Subsequently, the lack of any documentary evidence, other than the results of the one medical examination, only added fuel to the fire, and increased the number of people that believed in a conspiracy theory.

Who, in their opinion, could have been guilty of the death of a talented prime minister, who bravely and calmly lead the country through a difficult military conflict? People who do not trust the official version have two different theories.

A Pakistani plot?

The first is that the murder of Lal Bahadur Shastri was organized by the Pakistani government. It is believed that the Prime Minister of India intended to continue talks with Ayub Khan after signing the Declaration. The purpose of these negotiations would have been to make the Ayub Khan promise to “never to use force against India,” and to finally renounce all territorial claims in Kashmir. Given India's tacit support from the Soviet Union, as well as several major failures of Pakistan in the war (for example, the battle of Asal Uttar), which demonstrated the weakening of the Pakistani military, Shastri could have counted on his demands being met. And so to prevent such a scenario, the Pakistani authorities staged an attack on the Indian Prime Minister, some believe.

However, that raises a question. Could Ayub Khan have made such a rash decision while in a foreign country, where the risk of failure increased many times? The consequences of a new conflict, which certainly would have started if the conspiracy had been uncovered, were completely unpredictable. Even if the plan had been successfully carried out, it would have been unlikely to assist the Pakistani leadership. Poisoning of a political opponent during negotiations in any case would have made Ayub Khan look suspicious, and probably would have caused an international scandal that would have jeopardised the diplomatic image of Pakistan.

In addition, according to the testimony of one of the head waiters, Ahmed Sattarov, the Soviet secret police carefully observed the preparations for the event: all of the food put on the table underwent laboratory analysis, and the staff was under constant surveillance. Could Pakistani agents really have carried out such a risky plan so easily?

Hand of Moscow

Proponents of the second version see the “hand of Moscow” in the incident. The USSR was allegedly unhappy with Nehru's policy of non-alignment, which Lal Bahadur Shastri consistently adhered to, and intended to bring more loyal forces to power in India. Some radical adherents consider Indira Gandhi, who became prime minister of India after the death of Shastri, to be a “Soviet stooge.” In this way they try to explain why information on the circumstances of the death of the Indian Prime Minister was never disclosed. The participation of the Soviet Union, it would seem, could explain how a political assassination could take place on Soviet territory.

But even a cursory analysis of this version reveals many weaknesses. For example: why would the Soviets change leadership in India if the 1950s saw Indo-Soviet rapprochement (a trade agreement in 1953, Nehru's visit to Moscow in 1955, the consideration of the Soviet Union as an ally in the confrontation with China), which only intensified during Shastri's tenure as Prime Minister?

Indira Gandhi, who was appointed by Lal Bahadur as Minister of Information and Broadcasting, was by no means his political enemy. On the contrary, among the other leaders of the Congress she supported Shastri when he went up against other politicians such as Morarji Desai. She was also not an ardent supporter of the alliance with the USSR (an explicit pro-Soviet stance can be seen in her politics only beginning in 1968-1969). Clearly, neither the “Soviet” version nor the “Pakistani” one looks very convincing.

So, what is known about the true causes of Lal Bahadur Shastri's death? After examining the most popular conspiracy theories, the official stance seems the most plausible. Hardships endured by Shastri, including the loss of loved ones, repeated periods of incarceration during India’s freedom struggle and the need to act in an extremely tense political situation could have affected the health of this brave man.

However, much of this story remains unclear. Why wasn't an autopsy performed on the body of the Prime Minister? Why are the Indian authorities afraid to publish the details of his death? Why did Shastri's son Sunil stubbornly refuse to believe that his father died of a heart attack? Whether we learn the answers to these questions, only time will tell…

}

Memories of head waiter Ahmed Sattarov

“In January 1966, a meeting was held in Tashkent between the heads of the governments of India and Pakistan, where they discussed ending the conflict between the warring countries. I was among the special group of head waiters from the Kremlin that was sent to work in Tashkent. Preparation took about a month. One of the things that we practiced was how to comply with the rules of etiquette. In this case, it was not easy, as European protocol is very different from Muslim and Hindu. An expensive, elegant set of dishes was made ready, that even included dining sets of the Emir of Bukhara that had been found in the vaults of the Ministry of Commerce of Uzbekistan.

After the pact was signed, a buffet-style banquet was held. After it was finished, the entire exhausted staff was called together, thanked, and awarded certificates. They promised me and some other head waiters to give us state awards in Moscow for all of our service. We went back to the hotel very happy.

Early in the morning I was woken by an officer of the Ninth Directorate of the KGB (who guarded members of the Politburo and the government), from whom I learned about the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri. The officer said that they suspected the Indian prime minister had been poisoned. They handcuffed me and three other head waiters, of which I was senior, and loaded us into a Chaika automobile. We four had served the most senior officials, and so we immediately came under suspicion.

They brought us to a small town called Bulmen, which is about thirty kilometres from the city, locked us in the basement of a three-story mansion, and stationed a guard. After a while, they brought the Indian chef who had cooked the Indian dishes for the banquet. We thought that it must have been that man who poisoned Shastri. We were so nervous that the hair on the temple of one of my colleagues turned gray before our eyes, and ever since I stutter.

We spent six hours in the basement; they seemed like an eternity. And finally, the door opened and a delegation led by Kosygin entered. He apologized to us, and said that we were free to go. A medical examination had shown that Shastri died a natural death from his fourth heart attack. Nevertheless, the foreign press dubbed us the ‘Poisoners of the Prime Minister of India.’ Only our country's newspapers showed restraint.”

Sattarov, who has rarely been interviewed since the incident, also answered a couple of questions.

The Ninth Directorate probably tightly controlled the whole banquet, including the quality of the food. Was there really an opportunity for such an attempt?

I think not. The food could not get onto the banquet table or into the refrigerators of the apartments of the heads of state without undergoing a complete laboratory analysis. Every movement of the staff was under the supervision of the KGB and other intelligence agencies.

Did you change your attitude toward the Kremlin after the incident?

Yes, for the better. Kosygin remembered me, said hello on occasion and even shook my hand. My boss also treated me well. But the changes took place in my heart. At that time I had been taking correspondence courses at Moscow State University. The six hours I spent in the basement at Bulmen in handcuffs made me promise myself that when I finished my studies, I would quit my job as head waiter. Soon I found work in a small newspaper. Later I published several books of poetry and essays. When the confidentiality term expired, I even wrote a memoir called Notes of a Kremlin Maitre d'.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox