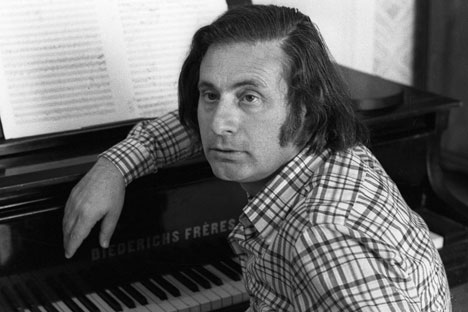

Alfred Schnittke. Source: RIA Novosti

Only a few Soviet composers in the 1970s and 1980s were able to gain recognition among Western colleagues and musicologists beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998) was one of the few.

At the same time, his works barely saw any performances in Soviet music halls because of a policy that did not support or allow “Western formalist” music. Now Schnittke is considered as one of the major Russian composers of the second half of the 20th century, among Shostakovich and Prokofiev.

Due to certain events, I was privileged to meet and know Alfred Schnittke. Here are some of my memories.

In 1980, I started the rock group Center (Центр) in Moscow with my friends, when we were students in Moscow’s institutes. We were interested and listened to new wave, avant-garde and experimental rock. Also, I was interested in the latest trends in the art world, such as Moscow’s conceptualism.

Center (1983). Source: YouTube

Sometime in 1982, I got a phone call from a grandmother of Andrei Schnittke, who was a guitar player in our band Center. She was saying that Andrei’s father, Alfred Garrievich Schnittke, had listened to one of our tapes that I recorded with our keyboard player Alexei Loktev and he liked it and would like to meet with us.

This tape was a 30-minute, free-form improvisation using heavily processed electric guitar and electric piano. We made this tape trying to lay down a bunch of our music ideas for future usage, as a foundation for our new songs. At this point, I didn’t know much about Alfred Schnittke, besides the fact that he was a composer and I saw his name few times in the music credits it Soviet movies.

A. Schnittke. “A Fairy Tale of Travels”. Source: YouTube

When I met Alfred for first time in his Moscow apartment, he played on his big black piano a few melodies from a popular German new wave group, Trio. I was actually surprised that a serious composer like Schnittke knew by heart and could play rock tunes on a piano correctly, with the right feel.

Also, I was very impressed with Alfred’s large LP collection with experimental and avant-garde music: albums by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Gyorgy Ligeti, Luciano Berio, Philip Glass, Steve Reich and other avant-garde and experimental composers.

Some albums included signatures saying something like: “To my friend and colleague Alfred Schnittke.” Pretty soon, I recorded many albums from Alfred’s LP collection to my tape reels, thanks to his permission to use his turntable and reel-to-reel recorder.

I spent long hours recording music form Alfred’s collection, and he was giving me very interesting comments about albums and composers. From our first meeting, I always felt his support and understanding of what we were doing as a young underground and experimental rock group.

Stockhausen. "Gesang der Junglinge". Source: YouTube

Luciano Berio. Sinfonia. Source: YouTube

Steve Reich. Music for Mallets Instruments, Voices and Organ. Source: YouTube

Philip Glass. Einstein on the Beach. Source: YouTube

After my avant-garde music reel collection expanded with many new additions thanks to Schnittke’s help, I received more visits from Moscow’s music journalists and musicologists, who were curious about sound recordings from modern Western composers that were hard to find in the Soviet Union.

At the same time, I learned about the uneasy situation for Alfred Schnittke with the Union of Soviet Composers. By law, every citizen in the Soviet Union had to have an official government job. For creative types, so-called artistic unions were created by Stalin in the 1930s, such as the unions of writers, journalists, composers, and artists.

Membership in the Union of Composers gave official job status and also provided an opportunity for publishing and performances by state orchestras of works by union members, which led to an income that could be well above the average monthly salary of workers in the Soviet Union.

Schnittke didn’t enjoy any of those perks and benefits. His works were basically blacklisted. This situation was due to an ongoing rejection of any type of Western influences on Soviet ideology. Since music in the Soviet Union was part of ideology, composer’s works and their lives were under control and scrutiny.

For a better understanding of what type of atmosphere was established in the Union of Composers starting from the 1940s until Gorbachev’s perestroika in the mid-‘80s, let’s just mention that it was led by a hardline Stalinist type of bureaucrat composer, Tikhon Nikolayevich Khrennikov (1913-2007).

Khrennikov was appointed as the General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948 by Stalin’s henchman, Andrei Zhdanov. He held this position until 1991. Under Khrennikov’s watch, many repressive ideological, anti-Western-influence campaigns were conducted in the Union of Composers — “against formalists in music” and “against cosmopolitans,” just to name a few.

Khrennikov established himself as a valuable enforcer of Central Committee ideological rules and guidelines, which lead to his unprecedented long career as a Chairman of the Union of Composers. Alfred Schnittke’s works in “polystylism” included various, modern, Western music techniques that were suppressed under Khrennikov’s rule.

Since no one could contest Schnittke’s professionalism and skills as a composer, he was kept in the Union without opportunities for regular income. Symphony orchestras in major Soviet cities such as Moscow and Leningrad refused to play Schnittke’s compositions, and only regional philharmonic orchestras sometimes took a chance and included Schnittke in their repertoire — at the their own risk of losing their jobs for this type of anti-Soviet behavior.

Schnittke’s difficulties in the Soviet Union also rose due to his German and Jewish heritage. He was born in 1934, in the city of Engels, where the Volga-German republic of the Soviet Union was located. His father was Jewish and his mother was German.

During the first years of his life, Schnittke spoke only in German with his mother and learned how to speak Russian later. With this type of heritage, Schnittke was treated as “not one of us” and as a “suspect” by the totalitarian Soviet system, in which anti-Semitism was a part of Stalin’s propaganda.

Considering all types of pressure and the limited options for performing his music in the Soviet Union, Schnittke was very productive. His music catalogue included around 70 pieces of various works such as symphonies, operas, ballets, chamber and choral music.

A. Schnittke. Concerto Grosso no.1 (1977). Source: YouTube

A. Schnittke. Seid nüchtern und wachet... (VII). Source: YouTube

A. Schnittke. “Concerto for Piano and String Orchestra”. Source: YouTube

Looking for other ways to make a living and provide for his family, Schnittke turned to the Soviet film industry. To write a score for a film was much easier, because this type of project did not require approval from Khrennikov’s Union of Composers.

Also, in Soviet movies, censorship was concentrated mostly on the script and visuals of the picture, leaving soundtrack decisions to the film’s director. Looking back at Soviet movies, almost all types of Western styles and influences can be heard in the music scores.

Schnittke composed music scores to numerous Soviet films, working with famous Soviet film and animation directors. He is credited as the composer for more then 60 feature films.

A. Schnittke. “Voland” (from the film “The Master and Margarita”). Source: YouTube

A. Schnittke. Polka from suite "Census Tale". Source: YouTube

A song from the "Small tragedies" film. Source: YouTube

In 1983, Alfred told me that he was starting to work on a new film with the director Igor Talankin, for Mosfilm movie studios in Moscow. In this new film, one scene was to be shot at the cruise ship’s bar, where a young rock group would be playing.

Schnittke was hinting that our group Center should be this band. Director Talankin took Alfred’s advice and they visited us at our small recording place for an introduction and a kind of casting. Talankin was hesitant at first, because our own rock songs were a kind of alien music style for him; but Schnittke convinced him that our band represented a new generation and would be great for the scene.

Talankin took our tape and left saying that he’d think more about it. A few months later, I got a phone call from Mosfilm studios’ music department informing me that I needed to visit them and pick up a script for Talankin’s new picture.

I wasn’t sure why I needed the whole script, since we were talking about our band’s participation in a small scene at the bar. When I arrived at Mosfilm, I learned that some changes had been made during preproduction and Schnittke would not be composing the music score: The director decided to make one of our band’s songs the main theme for the picture. In addition, the director wanted us to write and record a few more melodies for the film’s soundtrack.

Alfred never told us all the details, but I am sure that he convinced Talankin to use us as composers for this film instead of him, because there were a bunch of seasoned Mosfilm composers who would take this project in the blink of an eye.

This shows how great Alfred was as a human being, helping others without asking anything in return. He probably felt that, based on his life experiences, our young underground and experimental band would face a lot of problems from the totalitarian system, because rock music in the Soviet Union was treated as some kind of anti-Soviet ideological sabotage.

When we went to Mosfilm in 1984 for a screening of this film (called “Vacation time from Saturday till Monday”), we were expecting that all our scenes had been removed from a final cut and the band’s name would not show up in the credits due to censorship. To our huge surprise, we were there!

Alfred also introduced our band to a famous Soviet animation film director, Andrei Khrzhanovsky (born 1939), and recommended him to work with us as composers on his new animation film “King’s Breakfast,” which was being made by Soyuzmultfilm studio.

With perestroika changes and a more open society in the Soviet Union after 1985, Schnittke gained much-deserved widespread recognition and was able to travel abroad, where his works were performed by symphony orchestras in Europe and in the United States.

In 1990, Schnittke moved to Hamburg, Germany, where he lived and worked up to his death in 1998. He is buried in Moscow’s Novadevichy Cemetery, among many other significant Russian figures such as Boris Yeltsin, Nikita Khrushchev and Dmitri Shostakovich.

I am glad that I had a chance to meet and know Alfred Schnittke as a friend, a mentor, and — most importantly — a great human being.

Vasily Shumov is a musician, producer, photo and video artist. Born in Moscow, he founded Moscow's first new-wave, electronic band, Center (Центр), in 1980.

From 1990 to 2008,Shumov lived in Los Angeles, California, graduating from the California Institute of the Arts with a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1998.

Vasily has presented numerous solo and group

exhibitions featuring his photo and video artwork. His most recent personal

photo art exhibition was held in April 2013, at the Central House of Artists in

Moscow. In June 2013, he performed with his band Center at PAX Festival in

Helsinki, Finland.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox